Momina Qazi

In Pakistan, the right of a woman to marry by her own choice remains one of the most contested yet essential aspects of individual liberty, Islamic principle, and constitutional law. While societal traditions often deny this right, both Islamic teachings and Pakistan’s Constitution uphold it unequivocally.

Islam recognizes a woman’s consent as an essential prerequisite for marriage. Numerous Hadiths of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ affirm this. One widely cited incident involves a woman whose father arranged her marriage without her consent. Upon hearing her complaint, the Prophet ﷺ declared the marriage invalid, setting a clear precedent: no marriage is valid without the woman’s willing approval. Jurisprudence across all Islamic schools supports this view. If a woman is of sound mind and has reached maturity, she has full authority over her marriage decision.

The Constitution of Pakistan also reinforces this right. Articles 9, 25, and 35 collectively guarantee personal liberty, equality before law, and protection of the family unit, respectively. The Supreme Court of Pakistan has on several occasions upheld the legality of marriages based on a woman’s free will, instructing law enforcement agencies to protect such unions.

Yet the reality for many women is starkly different. Cultural customs such as caste barriers, notions of family honor, tribal norms, and false concepts of “ghairat” (honor) continue to suffocate women’s autonomy. A woman choosing her partner is often labeled rebellious, immoral, or dishonorable. This contradiction between law and practice reflects the broader resistance of patriarchal society against female empowerment.

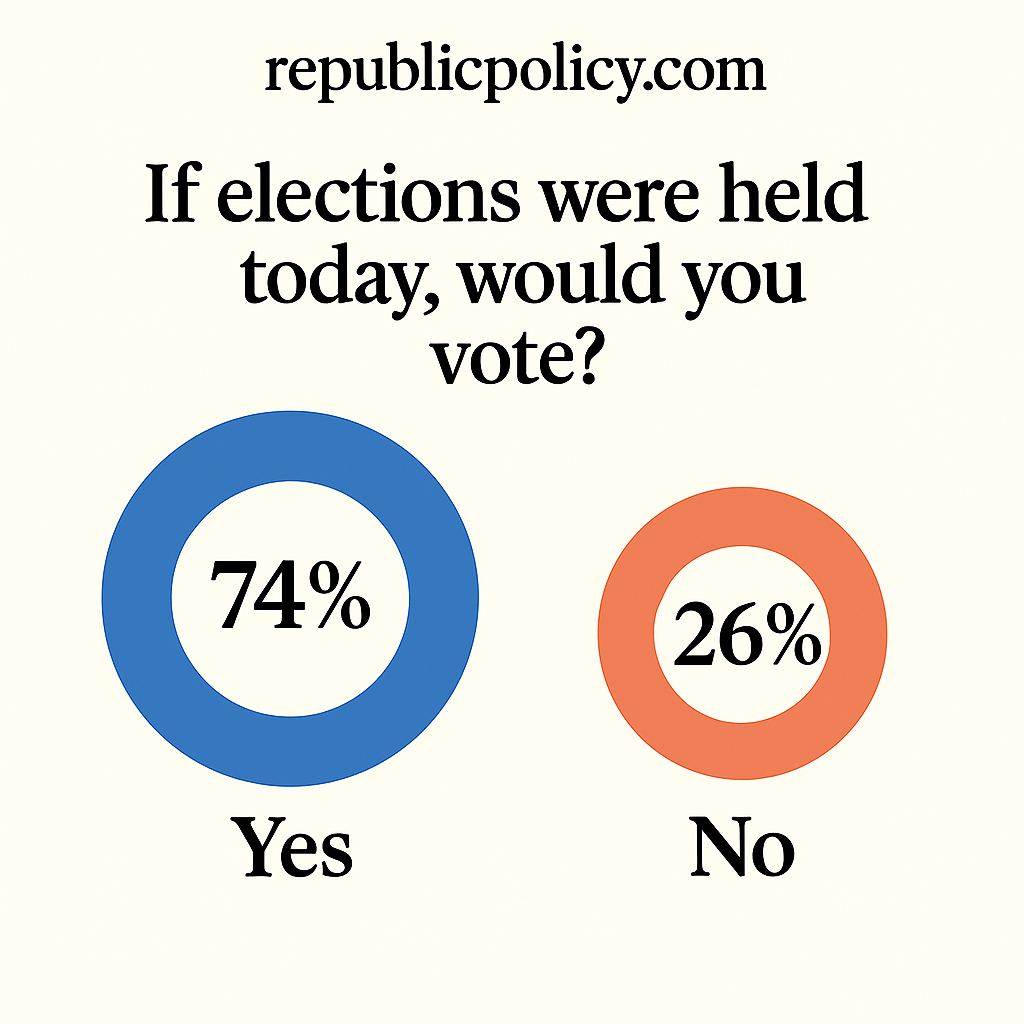

Please, subscribe to the YouTube channel of republicpolicy.com for quality content.

To transform this reality, a multi-dimensional approach is needed. First, effective implementation of existing laws is crucial. Families forcing women into unwanted marriages must face legal consequences. Secondly, religious leaders and scholars must use their platforms to educate communities on the actual teachings of Islam regarding consent in marriage. Third, media and education systems should launch campaigns to raise awareness among both men and women about the legal and religious legitimacy of a woman’s right to choose her spouse.

Additionally, society must redefine the concept of family consultation. Advising a daughter about marriage is valid—but only when the final decision remains hers. True consultation means support, not coercion.

Women’s networking and support systems are also vital. Platforms that allow women to share their experiences, offer legal guidance, and provide emotional support can empower many who feel isolated or threatened. Government and civil society must collaborate to create and promote such support structures.

The battle for a woman’s right to choose her life partner is not merely a personal or legal matter—it is a test of Pakistan’s commitment to justice, human rights, and the essence of Islam. Societies that suppress women’s basic freedoms cannot progress. On the contrary, societies that uphold these freedoms lay the groundwork for a more just, equal, and prosperous future.

In empowering women with this fundamental right, Pakistan is not Westernizing—it is, in fact, realigning with the true spirit of Islam and constitutional democracy. Recognizing and respecting a woman’s right to choose her husband is not just a step toward gender justice, it is a leap toward national integrity.

For more such insights, visit RepublicPolicy.com – your source for research-backed, rights-focused governance discourse in Pakistan.