Arshad Mahmood Awan

The recently released Labour Force Survey 2024-25 by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) has sparked widespread concern among economists, policymakers, and civil society. While it aims to provide a snapshot of employment trends across Pakistan, the survey raises more questions than answers, particularly when compared to data from the Population and Housing Census 2023. A glaring discrepancy between the two reports suggests significant methodological flaws. The survey reports unemployment at 7.1%, while the census puts it at a staggering 22.5%. Such a gap cannot simply be explained away as sampling error. Experts warn that the government should clarify these differences and address why the survey counts home-based poultry raisers as “employed,” a practice that appears designed to understate true unemployment.

Beyond questions of accuracy, the survey highlights serious structural problems in Pakistan’s labour market. The rise in unemployment from 6.3% four years ago to 7.1%—the highest in 21 years—reflects a deteriorating economic environment. The absolute number of unemployed individuals has surged by 31% to 5.9 million, demonstrating that the economy is failing to absorb the roughly 3.5 million new entrants to the workforce each year. With annual growth stagnating below 2%, job creation remains insufficient, leaving millions of youth and educated individuals without meaningful employment opportunities. Nearly one million degree holders are unemployed, a scenario that could fuel social unrest and widespread disillusionment if left unaddressed.

The crisis is particularly acute among youth aged 15-29 and women. The labour force participation of women remains exceptionally low, with three out of four working-age women engaged solely in unpaid domestic or care work. Out of 179.6 million working-age people, 117.4 million are confined to unpaid roles at home, highlighting persistent gender barriers that prevent meaningful economic inclusion. The impact of unemployment on women, especially in rural areas, further restricts household income and impedes broader socioeconomic development.

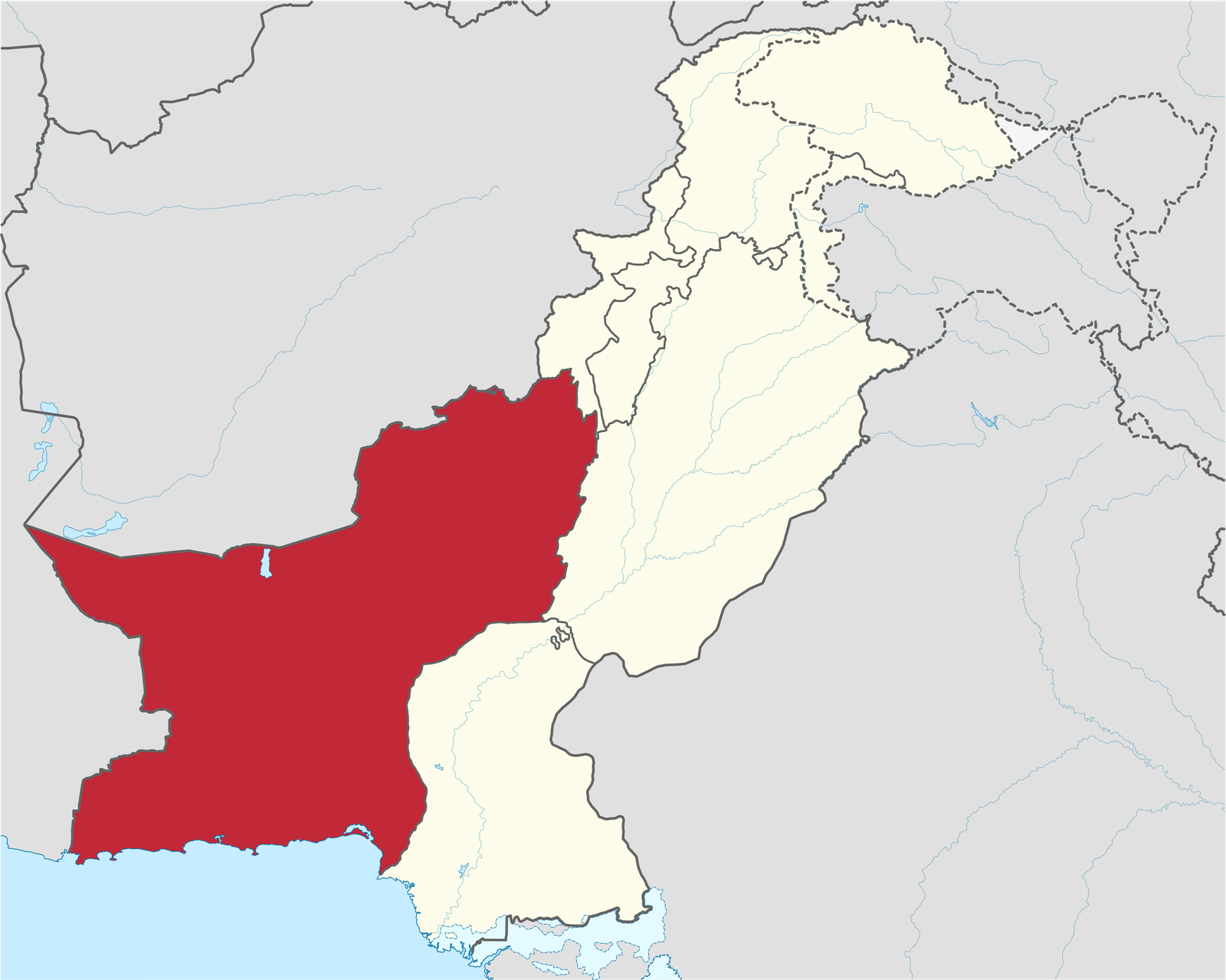

The sectoral composition of employment reveals troubling trends. Agricultural employment has declined from 37.4% to 33.1%, pushing workers towards low-paid, informal service-sector jobs in urban centres. This migration is symptomatic of a structural shift in the economy, where formal employment opportunities are limited, and informal, precarious work is growing. The survey also reflects significant regional disparities. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) has the highest unemployment rate at 9.6%, followed by Punjab at 7.1%, Balochistan at 5.5%, and Sindh at 5.3%. These differences underline the uneven distribution of economic opportunities across provinces, which could exacerbate inter-regional inequalities and political tensions.

Real wage stagnation compounds the crisis. Although average wages appear to have increased nominally, inflation has eroded purchasing power, leaving employed citizens earning less in real terms than in 2021. For the vast majority of workers, especially daily-wage earners in urban informal sectors, rising prices outweigh income growth, deepening vulnerability and economic insecurity.

Addressing these challenges requires a shift in policy focus. Economic stabilisation rhetoric alone is insufficient. Authorities must tackle structural barriers that constrain employment generation. Pakistan’s business climate is still unfriendly to investors and entrepreneurs, while the shortage of skilled workforce limits competitiveness. Gender barriers remain entrenched, preventing women from entering formal employment in meaningful numbers. Agriculture and industry, traditionally critical sectors for job creation, are underinvested, contributing to rural distress and urban migration. Without targeted reforms in these sectors, Pakistan risks further deterioration of its labour market.

A multi-pronged approach is essential. First, the government must implement comprehensive labour reforms to promote formal employment, especially for youth and women. Policies should incentivise skill development, vocational training, and entrepreneurship, aligning workforce capabilities with emerging sectors. Second, gender inclusion must become a central priority. Strategies to bring women into the formal economy—including childcare support, safe workplaces, and legal protections—can significantly expand labour participation and enhance household incomes. Third, provincial disparities require tailored interventions, with targeted investments in regions like KP and Balochistan to create local employment opportunities and reduce migration pressures.

Agriculture and industry can no longer remain sidelined. Investments in modern farming techniques, agro-processing, and small-scale industrial clusters can generate large-scale employment. Public-private partnerships should be encouraged to stimulate entrepreneurship and manufacturing growth, particularly in regions with high unemployment. Simultaneously, social protection systems must expand to cover vulnerable groups, mitigating the immediate effects of poverty while structural reforms take root.

Pakistan’s labour market crisis is not only an economic issue; it is a social and political challenge. High unemployment, especially among educated youth, carries risks of unrest and societal disillusionment. The persistence of informal work and gendered exclusion undermines long-term development goals, limiting productivity and national growth. If policymakers fail to act decisively, unemployment could continue rising, deepening poverty and exacerbating inequality.

The Labour Force Survey 2024-25 should be treated as a wake-up call. Accurate data collection, transparency, and accountability are critical. The government must explain the discrepancies with the Population and Housing Census, adopt rigorous survey methodologies, and ensure labour statistics reflect real conditions. Only then can informed, effective policies be designed to address the structural unemployment crisis.

Ultimately, Pakistan requires strategic, inclusive, and forward-looking policies that prioritise job creation, skills development, and gender inclusion. Tackling the labour market crisis is essential not only for economic stability but also for social cohesion and national resilience. Without urgent attention, the growing numbers of unemployed youth, women, and educated individuals could pose long-term challenges to Pakistan’s development and stability. Policymakers must move beyond rhetoric and implement reforms that generate employment, reduce poverty, and empower the workforce, securing a sustainable future for the nation.