Arshad Mahmood Awan

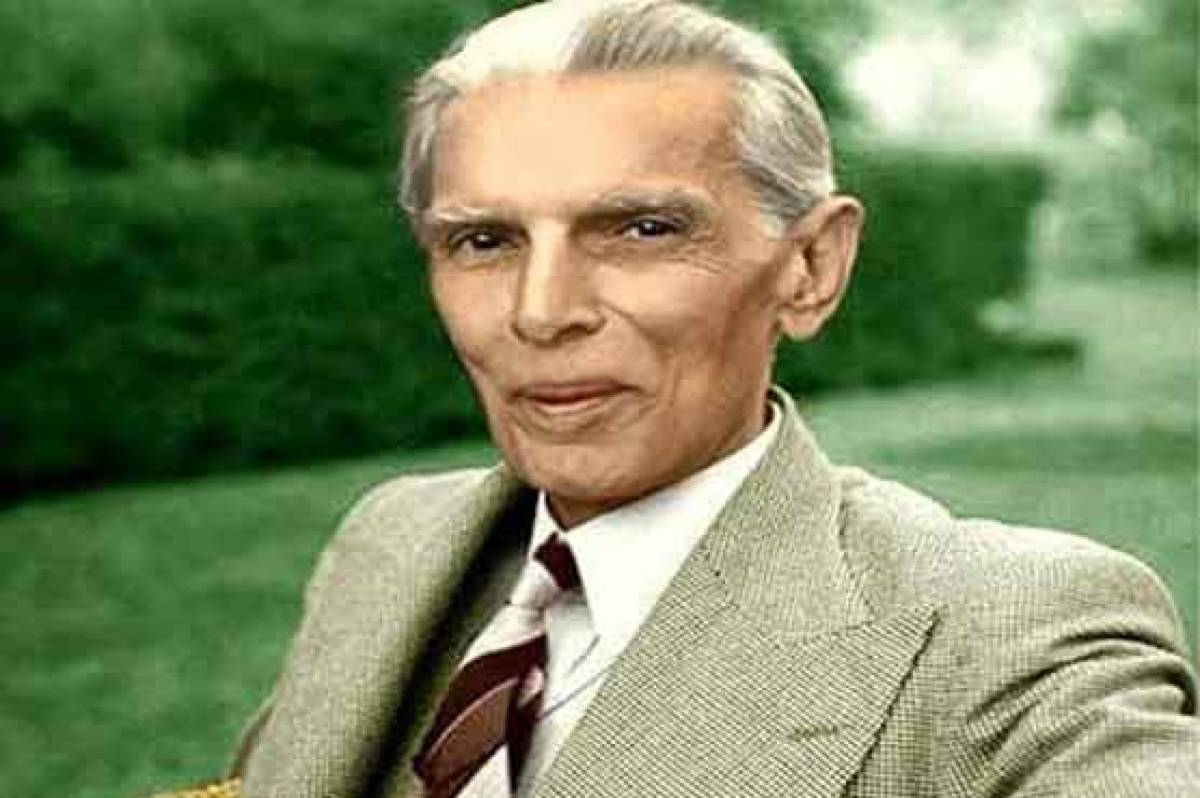

Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s political philosophy rested on two clear and inseparable principles. The first was republicanism: the belief that sovereignty belongs to the people, that authority flows upward from citizens through their vote, and that governments derive legitimacy only from public consent. In Jinnah’s understanding, the state was not the property of any individual, institution, or elite group. It was a trust held on behalf of the people, to be exercised strictly within constitutional limits.

The second foundational principle of Jinnah’s political thought was federalism. He envisioned a strong federation built on strong and genuinely autonomous provinces. He was deeply opposed to excessive centralisation of power and believed that authority must be dispersed rather than concentrated. Power, in his view, should flow downward to provinces and local levels, ensuring balance within the state rather than domination by a central authority. For Jinnah, a durable state was one rooted in equilibrium, not coercion.

These two ideas; democracy and federalism, were not separate or optional components of his vision. They were two pillars of a single political philosophy. Popular sovereignty without provincial autonomy would be hollow, and federalism without democratic representation would be meaningless. Jinnah wanted Pakistan to emerge as a modern, constitutional, and people-centred state, governed by law and sustained by consent.

Yet, from the very beginning, Pakistan’s state institutions and bureaucratic mindset failed to translate these principles into practice. The dominant state ideology that took shape after independence leaned heavily towards centralisation. The prevailing assumption was that the state could only remain strong if power was tightly concentrated at the centre. This belief shaped policy choices for decades. Provinces were weakened, local governments were sidelined, and federalism was reduced to an administrative arrangement rather than a political commitment.

Democracy suffered a similar fate. Instead of being treated as the foundation of the state, it was viewed as a risk to stability. Public opinion was seen as unpredictable and potentially destabilising, rather than as a source of legitimacy. As a result, powerful groups repeatedly intervened in political processes, sometimes through direct intervention and at other times through managed elections and controlled political outcomes. The vote was turned into a procedural formality rather than a decisive instrument of power.

This is where the Pakistani state’s deepest intellectual contradiction emerges. The state officially recognises Quaid-e-Azam as the founder of the nation, yet it consistently disregards his core political ideas. His speeches are quoted, his portraits are displayed, and his name is invoked during every national crisis. Each time, there are calls to “return to Jinnah’s vision.” But when that vision is articulated in practical terms, through demands for genuine federalism and real democracy, it is quietly set aside.

This contradiction is not symbolic; it is structural. The state says one thing, does another, and implements something entirely different. This gap between declared ideals and actual governance is the essence of intellectual dishonesty. The official narrative celebrates constitutionalism, democracy, and unity, while the operational reality prioritises control, centralisation, and elite management of power. Over time, this mismatch has eroded public trust and widened the distance between the state and its citizens.

Nowhere is this contradiction more visible than on December 25, when Quaid-e-Azam is officially commemorated. The day is marked with speeches, ceremonies, and solemn pledges. Yet, for the rest of the year, his ideas remain suspended. This is respect at the level of symbolism, not loyalty at the level of thought. If Jinnah is truly accepted as the country’s guiding figure, then his principles must shape policy, institutions, and political practice. Weakening federalism and tightly controlling democracy while invoking his name reduces his legacy to a slogan.

Pakistan’s crises are often described as economic, administrative, or security-related. But at their core, they are intellectual and political. A state that is not honest with its founding vision cannot be fully honest with its people. When foundational principles are selectively remembered and selectively ignored, reform becomes cosmetic rather than transformative. Institutions may change their language, but not their behaviour.

The refusal to fully embrace federalism has had lasting consequences. Smaller provinces have repeatedly felt marginalised, fuelling grievances and weakening national cohesion. The absence of empowered local governments has deprived citizens of meaningful participation in decision-making. Centralised authority may appear efficient in the short term, but it undermines resilience and legitimacy in the long run.

Similarly, democracy that is managed rather than trusted breeds cynicism. When people believe that outcomes are predetermined and their votes do not truly matter, political participation declines. This creates a vicious cycle: low trust justifies more control, and more control further erodes trust. Jinnah’s republican vision sought to break this cycle by making the people the true custodians of the state.

Pakistan does not need a new ideology or a reinvented national narrative. It already has one in the political philosophy of its founder. What it lacks is the courage to accept that philosophy honestly and in full. Embracing Jinnah’s vision means accepting the risks and responsibilities that come with democracy and federalism. It means trusting citizens, empowering provinces, and allowing political outcomes to reflect popular will rather than administrative convenience.

Until the state confronts its intellectual dishonesty, until it aligns its practices with its professed ideals, no reform can be lasting. Economic plans will falter, institutional restructuring will remain superficial, and political stability will continue to be elusive. The choice is not between tradition and change, or between order and chaos. The real choice is between symbolic reverence and genuine commitment.

Pakistan’s path to becoming a stable, just, and people-centred state lies not in new slogans, but in an honest return to Quaid-e-Azam’s original political vision. Democracy and federalism are not threats to the state; they are its constitutional lifeblood. This is a truth Pakistan has long avoided. Recognising it is the first step towards resolving the crises that continue to define the country’s political life.