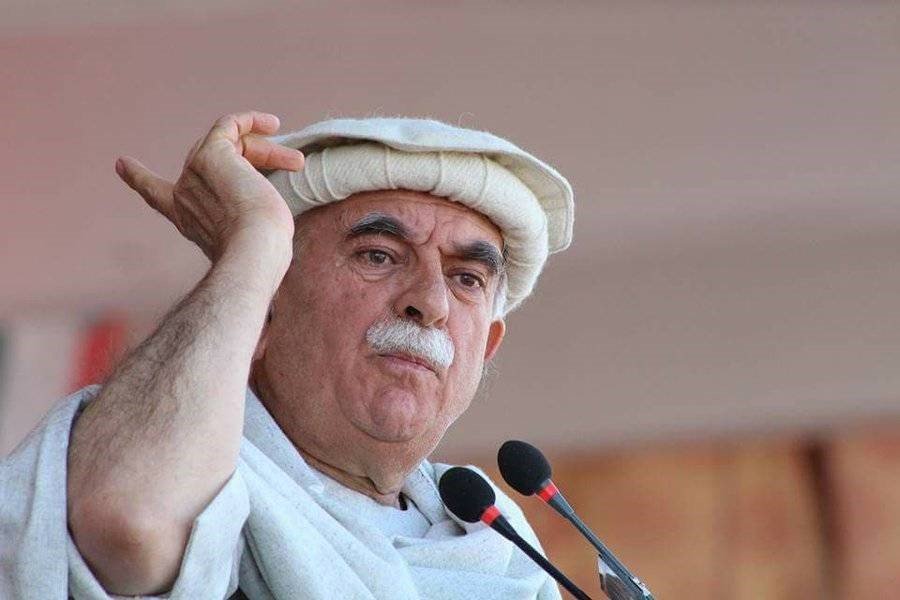

Abdullah Kamran

The latest session of the Senate Standing Committee on Interior has cast a stark light on Pakistan’s precarious cyber security landscape, highlighting serious vulnerabilities across critical state institutions, including NADRA and the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR). Repeated breaches in these agencies have resulted in the leakage of citizens’ sensitive personal data, raising urgent questions about the protection of private information in the country.

Senator Afnanullah Khan was particularly candid in his assessment, pointing to systemic failures in data protection. He warned that the sheer frequency and scale of data breaches could indicate potential official complicity, a worrying suggestion that underscores the gravity of the problem. Beyond that, the pattern of breaches exposes deep structural weaknesses in Pakistan’s cyber security framework. Consolidated datasets from NADRA, the FBR, and even the banking sector have surfaced on the dark web, illustrating both the sophistication of attackers and the inadequacy of existing defense systems.

The threat is not confined to the public sector. Private companies—including banks, telecom operators, and digital platforms—remain vulnerable to hacks, leaks, and organised cybercrime. Many continue to operate with outdated security protocols, insufficient staff training, and weak incident-response mechanisms. Meanwhile, attackers have grown increasingly sophisticated, employing automated tools, social engineering, and cross-database correlation to monetise stolen data at scale. This points to a deeper issue: cyber security in Pakistan is still not treated as a core governance or business risk backed by sustained investment, enforcement, and accountability, leaving both the state and private sector exposed in an increasingly hostile digital environment.

Pakistan’s ambitious digitalisation agenda has further amplified these risks. The Digital Nation Pakistan Act, passed last year, seeks to create a robust digital society and economy, promoting the provision of digital identities and the digitalisation of government departments. Yet, such a transformative vision brings serious vulnerabilities. Rapid digital expansion without critical safeguards creates large centralised data repositories, introduces multiple attack vectors, and increases the damage when breaches occur. The country’s digital push must therefore be accompanied by continuously evolving protective measures and safety protocols.

It is striking that Pakistan still lacks comprehensive data protection legislation. Citizens’ personal and financial information remains insufficiently safeguarded, and there is no statutory requirement for systematic investment in cyber security infrastructure. Frameworks to counter hacking, identity theft, financial fraud, and other digital crimes remain weak or incomplete. Recent government actions, such as throttling internet speeds and restricting VPN usage, have inadvertently exacerbated these weaknesses. Slower internet delays critical communication and security updates, while restricting VPNs undermines tools essential for online privacy and secure data handling, weakening both public and private systems.

Institutions such as the National Cyber Crime Investigation Agency have also been criticised for prioritising citizen surveillance over building true cyber resilience. The country’s low conviction rates for cybercrime further reflect this disconnect between policy focus and effective protection.

What Pakistan urgently needs is a recalibration of priorities. Cyber security must be placed above surveillance in the national digital agenda. Comprehensive data protection legislation is essential, mandating that all entities transitioning to digital platforms maintain the infrastructure, protocols, and expertise required to safeguard their systems against evolving threats. Security upgrades and capacity building must be statutory, not optional, to stay ahead of attackers.

Equally critical is the establishment of an independent regulatory body staffed by cyber security experts rather than career bureaucrats. Such an authority would oversee enforcement, ensuring compliance with protective standards and addressing vulnerabilities before they can be exploited. Without a dedicated regulatory framework, the risks of rapid digital expansion may outweigh its benefits, undermining economic growth, governance, and citizen trust.

The Senate committee’s hearing is a timely warning. Pakistan’s digital ambitions can only succeed if backed by a serious, forward-looking commitment to cyber security—one that treats personal data protection, system resilience, and regulatory oversight as inseparable components of the nation’s digital future.