Naveed Ahmed Qazi

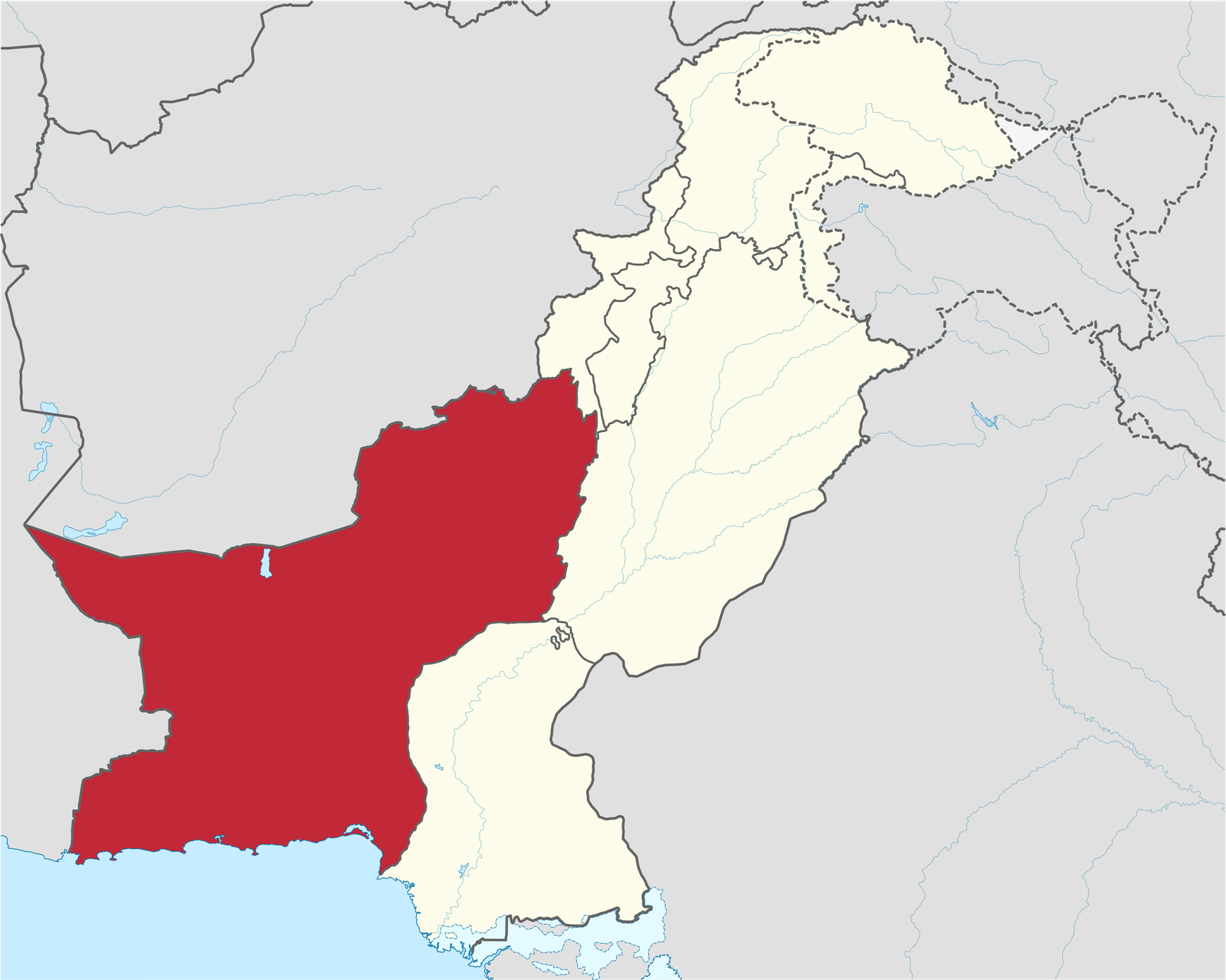

Saturday’s coordinated terrorist attacks across Balochistan—striking at least twelve cities including the provincial capital Quetta—have once again exposed the inadequacy of Pakistan’s approach to the province. Security forces killed numerous militants and prevented greater carnage through their sacrifices, but the very fact that insurgents could simultaneously target such widespread locations, including supposedly secure Quetta, reveals fundamental failures that no amount of intelligence-based operations can address.

The statistics paint a grim picture. Over 250 terrorist attacks occurred in Balochistan last year alone, causing more than 400 fatalities. Alongside Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the province endures the worst terrorist violence in Pakistan. This isn’t episodic unrest but a sustained insurgency that has persisted for decades, periodically erupting in coordinated campaigns like August 2024’s assaults and last year’s attack on the Jaffar Express.

The state’s response follows a predictable pattern: condemn the violence, praise security forces, conduct sanitization operations, impose Section 144 restrictions, and declare the situation under control. Federal ministers rush to the province for photo opportunities. Military officials announce body counts. Life returns to an uneasy normalcy until the next attack cycle begins.

The Counterterrorism Theater

Authorities point to foreign hands—hostile regional actors allegedly training and supporting Baloch separatists. This narrative, while partially true, conveniently deflects from examining why external actors find such fertile ground in Balochistan. Foreign intelligence agencies don’t create grievances from nothing; they exploit existing fissures that the Pakistani state itself has widened through decades of misgovernance.

The term “Fitna al-Hindustan” used officially for Baloch separatists reflects this shallow analysis. Branding domestic insurgency as merely foreign-sponsored allows the state to avoid confronting uncomfortable truths about its own conduct in Balochistan. Yes, external actors fuel the violence. But they’re exploiting genuine alienation created by Pakistan’s systematic violation of federalism and resource rights.

The interior minister’s rushed visit to assess the situation exemplifies this reactive approach. What assessment is needed that wasn’t already available after the previous attack, or the one before that? The problem isn’t insufficient information but unwillingness to implement solutions that threaten centralized control.

The Unasked Questions

How could militants simultaneously strike twelve locations across a province under heavy security presence? Where does their funding, weaponry, and intelligence come from? How do they move freely enough to coordinate such operations? These questions have obvious answers that implicate failures in governance, intelligence coordination, and border management.

But deeper questions remain deliberately unasked: Why does Balochistan, sitting atop immense natural wealth, remain Pakistan’s poorest province? Why do Baloch people see minimal benefit from resources extracted from their land? Why does the federal government, dominated by bureaucrats and institutions headquartered in Punjab, make critical decisions about Balochistan’s development without meaningful provincial input?

Beyond Kinetic Solutions

The editorial call for “sanitization operations” and “neutralizing violent actors” represents necessary but insufficient responses. Of course the state must protect citizens from terrorism. Of course those who murder innocents—including the women and children reportedly killed Saturday—cannot be tolerated. The brutal targeting of “non-locals” by some Baloch militant groups deserves unequivocal condemnation.

But counterterrorism operations without addressing root causes merely create temporary lulls before the next eruption. Pakistan has conducted countless operations in Balochistan over decades. Each claims success. Yet the insurgency persists and periodically intensifies.

The suggestion that “those estranged elements that renounce violence and pledge to respect the Constitution should be engaged by rulers” sounds reasonable but misses the fundamental point: Why should Baloch people respect a Constitution that Pakistan’s own state institutions systematically violate in Balochistan?

The Constitutional Betrayal

Balochistan’s crisis is ultimately constitutional. Pakistan’s Constitution promises provincial autonomy, resource rights, and federal governance. Article 172(3) explicitly states that mineral rights vest in provinces. The 18th Amendment strengthened provincial powers. Yet federal bureaucracy, dominated by centralized civil services, effectively administers Balochistan as a colony rather than a constitutionally equal province.

Natural gas flows from Balochistan to Punjab at subsidized rates while Baloch communities lack basic infrastructure. Mining contracts are awarded by federal ministries to companies with no local benefit-sharing. Development projects serve military and strategic interests rather than provincial needs. Provincial governments exercise minimal real authority over their own territory.

This isn’t federalism. It’s administrative occupation dressed in constitutional language.

The Path Not Taken

The editorial correctly notes that “until Balochistan’s natural wealth reaches its people, and alleviates their poverty and suffering, hostile actors will continue to exploit the situation.” But this understates the issue. It’s not about poverty alleviation through federal charity but about constitutional rights to resources and self-governance.

Lasting peace in Balochistan requires Pakistan to become what it claims to be: a federal democratic republic. This means implementing genuine provincial autonomy where Balochistan controls its resources, manages its development, and administers its territory through elected representatives rather than imposed bureaucrats.

It means ending the federal civil service’s illegal occupation of provincial posts—the same constitutional violation that perpetuates centralized control across Pakistan. It means respecting Article 172’s resource provisions rather than treating them as suggestions. It means allowing Balochistan’s people to benefit from their land’s wealth as a constitutional right, not federal benevolence.

Only after implementing these foundational principles does the state earn moral authority to confront those who still choose violence. Until then, Pakistan merely suppresses symptoms of a disease it continues spreading through its own constitutional violations. The terrorists understand this, even if the state pretends otherwise.