Naseeb khan

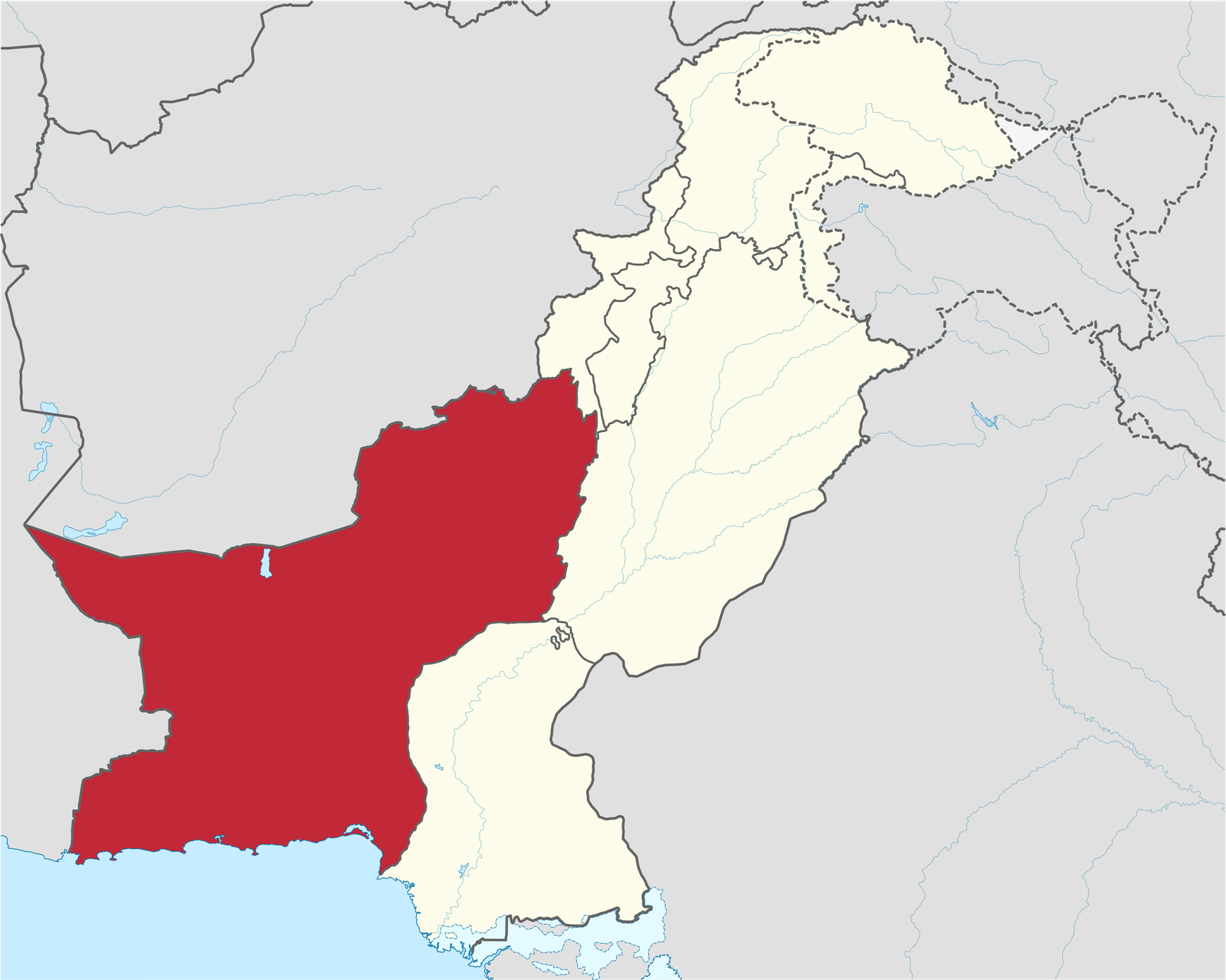

Balochistan once again finds itself gripped by violence that is neither random nor spontaneous. The coordinated terrorist attacks across more than a dozen cities and towns over the weekend were not acts of isolated desperation but a calculated attempt to destabilise Pakistan. The scale, timing, and coordination of these assaults—resulting in the martyrdom of security personnel and civilians alike—reflect a deep and dangerous design. While the security forces responded decisively, eliminating scores of militants within two days, the episode raises a more troubling question: why does Balochistan remain so vulnerable to repeated cycles of violence?

There is little ambiguity about the source of this unrest. Groups such as the Baloch Liberation Army have long operated with external patronage, exploiting local grievances to advance foreign geopolitical agendas. The presence of sophisticated weaponry, foreign operatives, and coordinated media campaigns exposes these militants not as homegrown revolutionaries but as proxies in a broader regional contest. The people of Balochistan are not the authors of this chaos; they are its primary victims, used as expendable tools in a war designed elsewhere.

The recent attacks targeted not only security installations but also banks, businesses, and public spaces. The intent was twofold: to spread fear and to disrupt economic life. The choreographed social media releases following the attacks further reveal that this violence is part of a well-managed external narrative, not a spontaneous uprising of the deprived. The myth that militancy in Balochistan is merely a reaction to poverty collapses when confronted with the evidence of foreign funding, training, and strategic direction.

Yet, acknowledging foreign interference alone is not enough. Balochistan’s volatility cannot be understood without confronting uncomfortable internal realities. The province has suffered from decades of weak governance, limited political ownership, and a persistent failure to meaningfully involve local communities in decisions that shape their lives. Development has often been extractive rather than inclusive. Authority has frequently appeared coercive rather than representative. These gaps have created fertile ground for hostile forces to manipulate frustration into rebellion.

What makes the current phase particularly alarming is the changing profile of militancy. Educated youth are increasingly being drawn into extremist networks. The emergence of suicide bombers, including women, marks a dangerous evolution that blurs the line between battlefield and civilian life. This not only complicates counterterrorism operations but also threatens to normalise violence as a form of expression, with devastating long-term consequences for society.

Pakistan has responded with force—and rightly so. No state can allow armed groups to challenge its writ or terrorise its citizens. The armed forces have demonstrated resolve and capability, conducting hundreds of intelligence-based operations and neutralising large numbers of militants. But history is unequivocal on one point: kinetic measures alone cannot deliver lasting peace in Balochistan.

The real battle is political.

If Balochistan is to be permanently stabilised, Pakistan must move beyond episodic security responses and address the structural alienation that allows militancy to recruit and regenerate. This requires a serious recommitment to federalism—not as a slogan, but as a lived political practice. Provinces must feel ownership of the federation, not subordination to it.

Representative government is the most powerful antidote to insurgency. When people see their voices reflected in decision-making, when resources are managed transparently by elected local leadership, and when accountability replaces administrative highhandedness, the space for militancy shrinks dramatically. Federalism strengthens unity not by force, but by consent.

Listening to the people of Balochistan is no longer optional. It is essential. Genuine dialogue, political inclusion, fair resource sharing, and respect for provincial autonomy are not concessions; they are constitutional obligations. Development projects must be shaped with local participation, not imposed through distant bureaucracies. Security must be paired with dignity.

Balochistan does not need sympathy—it needs partnership. The federation of Pakistan can only win hearts if it trusts its citizens enough to govern themselves through representative institutions. Terrorism thrives in silence and exclusion; democracy flourishes through voice and participation.

The choice is stark. Pakistan can continue fighting symptoms indefinitely, or it can treat the underlying political condition. Peace in Balochistan will not be secured by the gun alone. It will be secured when the people of the province see the federation not as an authority over them, but as a collective they truly belong to.