EDITORIAL:

As the 18th century progressed, two parallel stories unfolded, seemingly disconnected. One was the rapid rise of Britain’s dominance in the transatlantic slave trade. The number of enslaved people carried by British ships more than doubled, with estimates from the Slave Voyages database indicating that more than 830,000 were transported by the end of the century. The second story was the rise of William Shakespeare as the national bard, with his coronation as the King of English poets dating from the third quarter of the century.

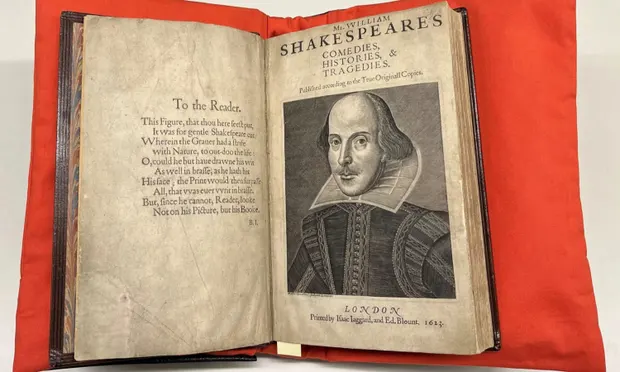

The convergence of these seemingly disparate stories lies in the valuable book known as Shakespeare’s First Folio, which was published 400 years ago in 1623. The history of this book contributes to ongoing debates about what happened to the vast profits made from the trade and exploitation of enslaved peoples in the late 18th century and beyond.

The sale of a rare original copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio for £2m highlights the book’s immense value, both historically and financially. But it also raises uncomfortable questions about the origins of the wealth that fueled the luxury goods market of the time, including the Wedgwood porcelain, Chippendale furniture, and valuable books that adorned the homes of the Georgian gentry.

The Trinidadian historian Eric Williams argued in his landmark study Capitalism and Slavery in the 1940s that the slave economy was the pump primer for Britain’s Industrial Revolution. He asserted that it was the development of alternative sources of profit through manufacture, rather than moral concerns, that motivated abolition. For other commentators, the profits from plantations fueled the Georgian gentry’s conspicuous consumption and extravagant spending, which stimulated the luxury goods market.

The value of Shakespeare’s First Folio has increased in tandem with the rise of Britain’s power and wealth, fueled in part by the profits of the transatlantic slave trade. This poses a troubling question: who paid the price for the wealth that enabled Shakespeare’s works to be valued and celebrated?

This uncomfortable truth reveals the deeply entwined history of Britain’s rise to power and its exploitation of enslaved peoples. Shakespeare’s First Folio serves as a symbol of this legacy, a reminder that the wealth and prestige it represents came at a great human cost.

As we continue to grapple with the legacy of slavery and its ongoing impact, it is vital that we confront the uncomfortable truths of our history. Only by acknowledging the past can we move forward with a more just and equitable society.

The 1623 publication of Shakespeare’s First Folio not only preserved half of the playwright’s plays, but also became a symbol of cultural and financial value. While it initially cost only £1, copies of the book have fetched increasingly exorbitant prices, a reflection of the historical circumstances surrounding its creation.

During the late 18th century, Britain’s transatlantic slave trade was booming, with British ships carrying more than 830,000 enslaved people, double the number transported in the first quarter of the century. At the same time, Shakespeare was being crowned as the “King of English poets” and the First Folio was gaining recognition as the authoritative text of the plays.

The overlap between these two seemingly disparate stories lies in the First Folio itself. Copies of the book were purchased by high-status men as a good investment, as well as a means of displaying their wealth and cultural refinement. However, the profits from the slave trade also fueled the luxury goods market, which included valuable books like the First Folio, as well as Wedgwood porcelain and Chippendale furniture.

But the provenance of certain copies of the First Folio also sheds light on the connection between Shakespeare and the slave trade. For example, a copy previously owned by John Fuller, a Sussex landowner and MP known for his patronage of JMW Turner, was recently sold at auction for almost $10m. Fuller’s estate and two Jamaican plantations, which included over 250 enslaved people, provided the funding for his lavish lifestyle and collection of valuable books, including a new copy of the First Folio.

It is ironic that a book which celebrates the genius of Shakespeare, a writer who frequently explored themes of morality and justice, is linked to the exploitation and enslavement of human beings. The First Folio, once a symbol of cultural and artistic significance, has become a trophy book for collectors, a tangible representation of wealth and status. It is a reminder that in the past, anything, including people, could be bought and sold.

As the debate continues about what happened to the profits made from the slave trade, the First Folio remains a potent symbol of the intertwined histories of culture, commerce, and exploitation. It is a testament to the power of art and literature to transcend time and place, and a reminder that the legacy of slavery continues to reverberate through our society today.

The celebration of the First Folio is undoubtedly warranted. Shakespeare’s plays would have been lost without it, and the Bard would not have risen to global cultural prominence. However, beyond its cultural and artistic value, the First Folio has also appreciated significantly in financial value.

When the book was first published, it cost only £1 or the equivalent of several years’ worth of penny theatre tickets. The earliest buyers were high-status men, such as a bishop, a young Kentish gentleman, and a nobleman. It proved to be a wise investment. Prices began to increase significantly in the mid-18th century as editors and scholars rediscovered it as the most authoritative text of Shakespeare’s plays, supplanting the previously held belief that the Fourth Folio was the most reliable. The Duke of Roxburghe, a renowned bibliophile, paid a staggering sum for a copy in 1790, sparking a price race that has continued unabated. The most recent copy sold at public auction reached almost $10 million.

The First Folio became a trophy book, a symbol of prestige and power. It was a time where anything, including human beings, could be bought for the right price.

The sale of a particular copy at Christie’s in New York by Mills, a private college in California, for a record-breaking amount ties together the economy of enslaved people and the increasing status of Shakespeare. The book previously belonged to the eccentric MP and Sussex landowner, John Fuller, who inherited the Rose Hill estate at Brightling in Sussex and two Jamaican plantations, including more than 250 enslaved people from his uncle. His lifestyle, which included patronage of JMW Turner and purchasing a new copy of the First Folio, was directly funded by enslaved labor. A half-hearted parliamentarian on most issues, Fuller used his voice most extensively as an outspoken anti-abolitionist, sneering at length in the House of Commons about the absurdity of the idea that “we should give up the benefit of the West Indies on account of the supposed hardships of the negro.”

In the early 19th century, Jack Fuller fought the East Sussex parliamentary election against a Whig opponent who focused on Fuller’s anti-abolitionism. One of the anti-Fuller campaign posters denounces plantation advertisements in harsh terms: “WANTED, For immediate service in the West Indies, about one thousand NEGRO DRIVERS, though none need apply but men who are muscular – who can lacerate the back of a Black to the bone at every infliction of the lash, and who have the courage to continue the stripes though his object should be writhing in the agonies of death.” It is not enough to argue that present standards should not be imposed on the past: Fuller’s support for slavery was recognized at the time as excessive, dehumanizing, and immoral.

Simultaneously, Fuller was acquiring a trophy book: the 1623 First Folio. In correspondence with the leading Shakespearean of the age, the Irish editor Edmond Malone, Fuller was assured that his copy was authentic and of excellent quality. It was a time when anything, including people, could be bought at a price. As we begin to examine the colonial underpinnings of the countryside, it is imperative to follow the money behind valuable books such as the First Folio, even our beloved Shakespeare. While the First Folio’s history is a testament to Shakespeare’s genius, it also has a darker history of money, power, and inequality.

In conclusion, the 1623 First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays is a fascinating piece of literature that has both cultural and financial value. While it is undoubtedly a significant classic and an essential artifact in the study of Shakespeare’s work, the book’s financial worth has increased dramatically over time. The history of the First Folio is also a history of inequality, as it was originally purchased by high-status men and later became a trophy book for the wealthy elite. The case of John Fuller, who owned a copy of the First Folio and also owned enslaved people, highlights the connections between the economy of enslaved labor and the increasing status of Shakespeare. As we continue to reckon with the colonial underpinnings of our society and the values that underlie the world of books, it is essential to examine the history of the First Folio and the many stories that it holds. We must acknowledge the darker aspects of this history while still celebrating the genius of Shakespeare’s works and their enduring cultural significance.

Acquire our monthly English and Urdu magazine promptly by accessing the Daraz App hyperlink!

https://www.daraz.pk/shop/3lyw0kmd

Read more: