Zafar Iqbal

The dynamics of our planet and the accelerating consequences of climate change have placed Asia’s energy transition at the very center of the global policy debate. From rising temperatures and extreme weather to food insecurity and public health crises, the costs of inaction are no longer abstract projections but lived realities. Asia, home to the majority of the world’s population and the fastest-growing energy demand, sits at a decisive crossroads. The region’s continued dependence on coal, oil, and gas, heavily subsidized for decades, has delivered growth but at an enormous climatic and fiscal cost. Delayed transition has amplified risks, increased the eventual cost of shifting to renewables, and narrowed the window for keeping global warming within manageable limits.

<a href=”https://www.republicpolicy.com” target=”_blank”>Follow Republic Policy</a>

Globally, the economic case for urgent climate action is overwhelming. Climate inaction already costs hundreds of billions of dollars annually through disasters, productivity losses, and damaged infrastructure. Projections suggest that under business-as-usual pathways, cumulative economic damage could reach into the thousands of trillions of dollars over this century, far exceeding the investment required to decarbonize energy systems. Health impacts alone, driven by heat stress, pollution, and food insecurity, are expected to impose trillions of dollars in costs by mid-century. Climate action, therefore, is not a moral luxury but an economic necessity. If effectively coordinated at multilateral platforms such as the Conference of Parties, it can still offer humanity a pathway away from irreversible harm.

<a href=”https://www.youtube.com/@TheRepublicPolicy” target=”_blank”>Follow Republic Policy on YouTube</a>

Yet the global context in which this transition must occur is deeply unsettled. The international system is experiencing fractures not seen since the aftermath of the Second World War. Strategic rivalries, geopolitical conflicts, and shifting domestic priorities among major powers are straining institutions that once underpinned collective development and climate action. Leadership is faltering, commitments are being reinterpreted, and trust is eroding. These fault lines threaten to slow decarbonization, fragment technology flows, and raise the cost of transition for developing regions. However, multilateralism itself is not collapsing. Rather, it is being reshaped. The central question is no longer whether cooperation will continue, but who will lead it and on what terms. For Asia, this moment is less a crisis than a call to assume responsibility commensurate with its economic and technological weight.

<a href=”https://x.com/republicpolicy” target=”_blank”>Follow Republic Policy on X</a>

A defining paradox of our time is that geopolitical fragmentation coexists with unprecedented momentum in clean energy deployment, much of it concentrated in Asia. While political tensions risk slowing global coordination, Asian economies, particularly China, have become the world’s hub for renewable energy manufacturing, battery production, and clean technology innovation. Massive additions of solar, wind, and storage capacity across the region demonstrate that the center of gravity in the energy transition has already shifted. Asia is no longer a peripheral participant in decarbonization; it is its engine. This reality brings both opportunity and responsibility. The region’s choices will largely determine whether global climate goals remain within reach.

<a href=”https://facebook.com/republicpolicy” target=”_blank”>Follow Republic Policy on Facebook</a>

Despite this progress, a significant gap persists between transition aspirations and energy realities. Global investment in renewables has reached record levels, yet the share of renewables in total final energy consumption has increased only gradually. This disconnect reflects the sheer scale and inertia of existing energy systems. Energy transitions unfold over decades, not election cycles. Studies consistently highlight that ambition alone is insufficient without cost competitiveness, reliable infrastructure, and solutions to what are often termed the “hard problems” of transition. Grid modernization, critical mineral supply chains, hydrogen infrastructure, long-duration storage, and carbon capture are complex, capital-intensive challenges that cannot be wished away. Asia’s transition must therefore be grounded in pragmatism as much as vision.

<a href=”https://www.tiktok.com/@republic_policy” target=”_blank”>Follow Republic Policy on TikTok</a>

For Asia, the stakes are enormous. The region holds the potential to unlock trillions of dollars in new revenue from clean energy and associated industries by 2030. At the same time, aligning with net-zero pathways will require multiplying annual investment to levels measured in trillions of dollars. The infrastructure gap is daunting. While initiatives such as the Asian Development Bank’s Energy Transition Mechanism offer promising pilots, particularly in Southeast Asia, they remain far from the scale required. Without predictable financing, strong implementation capacity, and political commitment, these efforts will struggle to deliver systemic change. Scaling up from pilots to transformation is the central challenge of the next decade.

<a href=”https://instagram.com/republicpolicy” target=”_blank”>Follow Republic Policy on Instagram</a>

Climate finance lies at the heart of this challenge. At recent climate summits, developed countries signaled intent to increase climate finance flows, with figures of hundreds of billions of dollars annually by the mid-2030s and aspirations to mobilize over a trillion dollars from public and private sources. Yet Asia alone requires investment on this order every year to remain on a credible net-zero trajectory. The gap between political intent and financial delivery is stark. Bridging it is not optional; it is a prerequisite for global success. Without adequate and timely finance, transition pathways in developing Asia will remain aspirational documents rather than executable plans.

<a href=”https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaYMzpX5Ui2WAdHrSg1G” target=”_blank”>Follow Republic Policy on WhatsApp</a>

The existing climate finance architecture is not fit for this purpose. Global funds operate below the scale required and often impose complex access requirements that strain limited institutional capacities in developing countries. Multilateral development banks face capital constraints that limit their ability to lend at the scale and tenor needed for long-gestation energy projects. Private capital, while abundant globally, remains risk-averse and gravitates toward markets where returns are predictable and risks are minimized. To unlock these flows, governments and institutions must deploy guarantees, first-loss instruments, standardized power purchase agreements, and transparent procurement frameworks. Innovative tools, such as the IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Framework, are steps in the right direction, but their impact depends on domestic capacity, project pipelines, and policy coherence.

Developing Asia confronts a difficult trilemma of fiscal constraints, energy security imperatives, and escalating climate risks. Structural reforms are necessary but insufficient on their own. What is required are co-designed solutions that reinforce macroeconomic stability while advancing climate ambition. This is where South, South cooperation must move from rhetoric to reality. If global mechanisms are slow to adapt, Asia must build complementary regional platforms that reflect its own priorities and constraints, without abandoning global engagement.

The building blocks for such cooperation already exist. Institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Asian Development Bank have demonstrated the capacity to mobilize significant capital for green infrastructure. Regional grid interconnection initiatives in South and Southeast Asia show that cross-border energy cooperation is technically feasible. What is missing is a unifying framework that brings these elements together at scale and speed.

A renewed Asian multilateralism for the energy transition can rest on three pillars. The first is the creation of a dedicated Asian Climate Transition Fund, capitalized by sovereign contributions, multilateral development banks, and private investors. Such a fund would provide patient capital for early coal retirement, grid modernization, large-scale storage, and renewable deployment. By offering concessional finance and absorbing early-stage risks, it could crowd in private investment and address the persistent gap between commitments and implementation.

The second pillar is regional technology cooperation and supply chain integration. Asia’s strength in clean energy manufacturing, particularly China’s leadership in solar, wind, and batteries, must be leveraged for regional benefit. At the same time, diversification of supply chains, common standards, joint research and development, and workforce training are essential to ensure resilience and shared prosperity. Technology cooperation should be seen not as a zero-sum competition but as a collective accelerator.

The third pillar is a just transition framework with real implementation capacity. Energy transitions that ignore social realities risk backlash and failure. District-level planning, robust social protection, reskilling programs, and community benefit mechanisms are essential to support workers and regions dependent on fossil fuels. Equally important is ensuring that decarbonization does not compromise energy access and affordability, particularly for the millions across Asia who still lack reliable electricity. Empowering local governments through targeted grants and technical support can anchor the transition in lived realities rather than distant capitals.

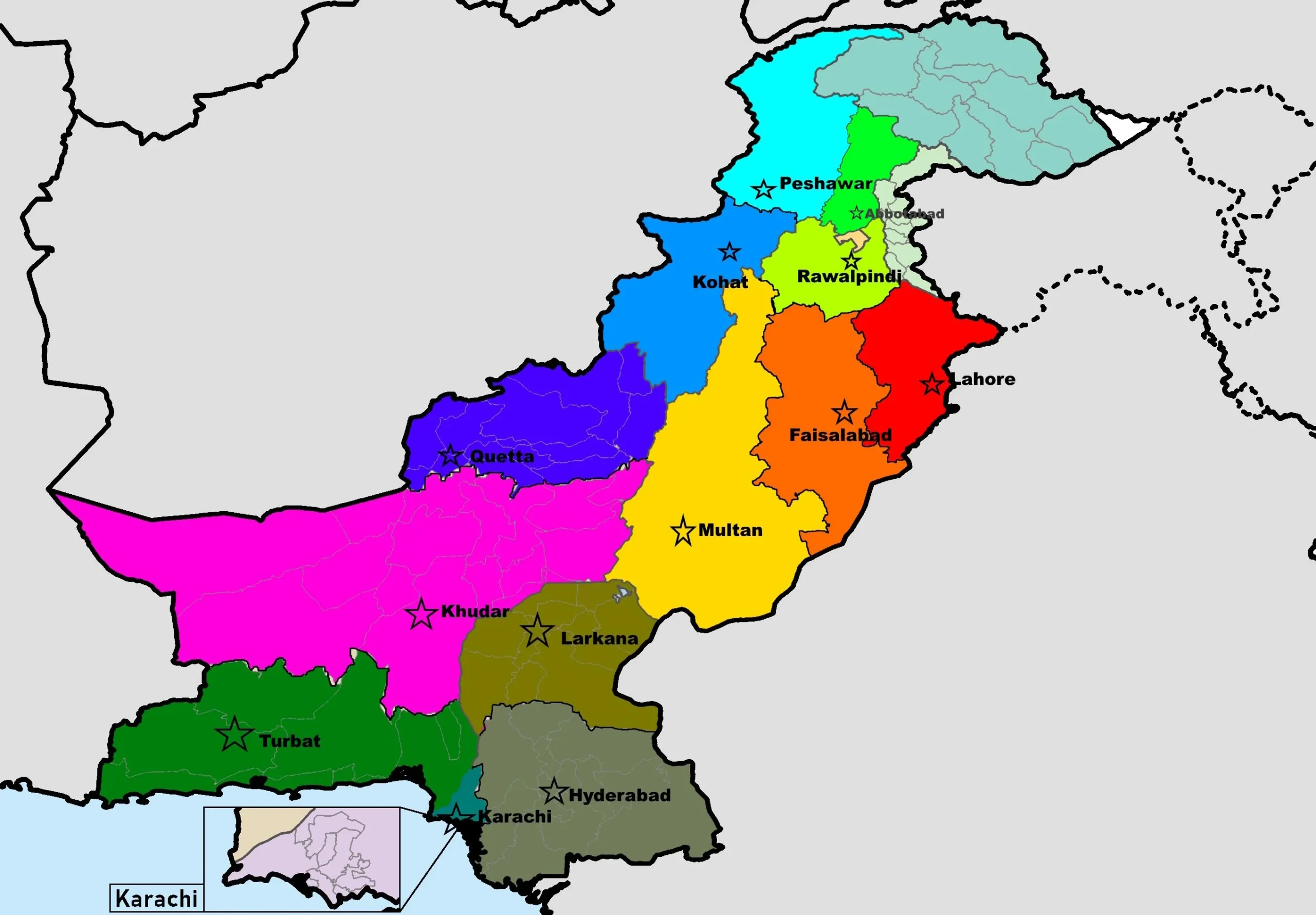

Pakistan offers a revealing case study of both the challenges and possibilities facing the region. Its recent engagements with the IMF, including the Extended Fund Facility and the Resilience and Sustainability Framework, provide a structured, albeit imperfect, platform for integrating climate considerations into macroeconomic policy. The focus on public investment management, water governance, disaster financing, and climate risk disclosure is appropriate. However, success hinges entirely on implementation.

Pakistan must bridge persistent federal–provincial divides that have fragmented climate governance since decentralization. Updated national climate commitments must translate into binding provincial action plans with dedicated budgets and clear timelines. Energy security requires a portfolio approach that prioritizes the retirement of the most polluting assets while investing in modern grids capable of integrating variable renewables. Private capital must be mobilized through credible regulation, contract sanctity, and transparent tariff structures. Above all, credibility must be rebuilt through rigorous monitoring, reporting, and verification.

Pakistan’s climate vulnerability underscores the urgency. Devastating floods and recurrent extreme weather have imposed enormous human and economic costs. While updated climate commitments are ambitious, delivery remains uncertain, constrained by fiscal pressures and institutional weaknesses. This dilemma is not unique to Pakistan; it reflects a broader challenge across the developing world, where climate finance is often tied to macroeconomic stabilization programs that must balance short-term stability with long-term transformation.

The path forward lies in integrated design. Fiscal reforms must be sequenced alongside targeted green investments, leveraging blended finance and scalable project pipelines. Regional partnerships, including with China under frameworks such as the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, can be recalibrated to align energy infrastructure with flexibility, affordability, and decarbonization goals. At the same time, emerging trade regimes, such as carbon border adjustment mechanisms, make decarbonization a competitiveness imperative, not merely an environmental one.

Asia’s energy future will be shaped by how it navigates an emerging global order characterized by climate clubs and selective alliances. There is a risk of a tiered system in which countries with capital and technology advance rapidly while others fall behind despite genuine ambition. Asia’s response must be strategic unity without forced conformity. Coordinated positions in global negotiations should coexist with flexible national pathways that reflect diverse circumstances.

In conclusion, building a fit-for-purpose multilateral order for Asia’s energy transition requires a new set of guiding principles. Equity must be paired with accountability, ensuring that differentiated responsibilities translate into measurable action. Localization of solutions must operate within shared standards that enable cooperation and trade. Flexibility in sequencing must not dilute ambition or exceed planetary boundaries. Public leadership must actively crowd in private partnership through real risk-sharing. South–South cooperation must complement, not replace, North–South obligations, recognizing climate finance as both responsibility and opportunity.

We stand at a defining inflection point. The old multilateral order is under strain, and a new one is still emerging. Such interregnums are dangerous but also fertile. Asia, with its scale, dynamism, and vulnerability, has a unique opportunity to shape a more inclusive, action-oriented, and accountable system of cooperation. The window for limiting warming to well below two degrees Celsius is narrowing, but it has not yet closed. Whether Asia and the world act decisively now will determine not only the trajectory of the global energy system, but the future of billions who depend on it. The time for moving from diagnosis to implementation is now.