Khalid Masood Khan

The mind-body duality and its antithetical idea of the mind being a mere illusion created on top of complex matter have long been debated in philosophical circles.

Throughout history, various thinkers, from Aristotle to Ibn Rushd, have attempted to understand the reality of the individual and its connection to the cosmos. Aristotle believed in the presence of an all-present Active Intellect that manifests in matter and its events, while Ibn Rushd posited the idea of an all-present ruh manifesting in innumerable accidents known as nafs. Both philosophers attempted to connect the individual soul with a super-soul, but their ideas were met with skepticism due to the lack of evidence for such an existence.

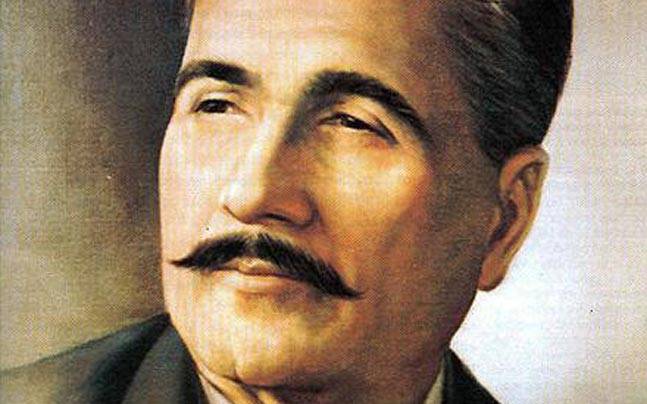

Iqbal, however, sees no reason to deny the existence of the self as he believes it is the essence of reality. In his pursuit of finding concrete evidence for the self, Iqbal follows a line of reasoning in which he identifies one particular accident, the self, among the innumerable accidents in the fabric of known reality. He then traces its trail back to the larger, seemingly all-present creative self. This leads Iqbal to the conclusion that the human self, or ego, persists unaltered in the flux of accidents experienced as states of the nafs. In other words, there is a self and there is its experience.

Iqbal’s goal is to establish the unity of the ego in order to escape the narrow mind-body debate. He rejects the idea of a passive soul that merely observes events or a soul that is a mere illusion. Instead, Iqbal believes in a mind-body connection, in which the mind is inseparable from the body. The self, being an indivisible entity, knows and realizes itself as it experiences the physical world around it.

Iqbal’s views differ from those of the mutakallimun, who followed the Greek line of thought. Ibn Rushd, for example, viewed the soul as a finer kind of matter or a mere accident that dies with the body and is recreated on the Day of Judgment. This idea was rooted in Aristotle’s two minds: the maker and the become. The maker is the ultimate creative power and possessor of the Active Intellect, while the become is merely a passive intellect that appears as accidents on the fabric of a finer matter, which is one, universal, and eternal. Ibn Rushd equated the first mind with the Quranic ruh and the second with its nafs, making the self’s appearance to itself as an independent actor a mere illusion. This led to pantheism, wherein the only possible truth would be of God Himself, and everything else would be a manifestation of His ongoing acts.

Iqbal’s argument, which diverges from conventional thought, proposes a “unity of ego” that recognizes the unique individuality of every human being. This individuality is apparent in the unity of the conscience and the unity of the inner experience, and it is not achieved by negating the material world. In Iqbal’s view, the “secular” is just as sacred as the “spiritual” because it also has its origin in the creative power of the Ultimate Ego.

In his effort to grapple with the duality of body and soul, Iqbal arrives at the conclusion that khalq and amr are properties of the same Creative Power. Whatever takes physical form also has activity and laws governing that activity. The amr from Allah is an integral part of that body, and creation and its mode of action cannot be separated. The body, Allah’s khalq, is made up of innumerable constituents, each working in accordance with the directives assigned by the Divine. Along with this mechanistic directive, there is a conscience, a knowing that manifests in every constituent. This knowing is the ego, the “I.”

Iqbal equates this “I” with the Quranic nafs, a life-bearing, self-conscious being that is conscious of its environment and connected to it. Thus, every entity, no matter how small, possesses an ego, and every complex whole has an ego of its own. All things possess self-awareness, and the Quran speaks of the nafs of the planet in Surah Takwir. “And the night, when it slows down,” “and the morning, when it enlivens (tanaffus),” as if the whole earth is awakened, and all things become self-aware with the light and energy of the day. At another place, God says of Himself, “…He has decreed upon Himself (nafsahu) mercy…” (6:12), implying that Allah Himself has a self, a consciousness, an “I” that knows.

As a result of its self-aware conscience, this “self” possesses a mental space as well as a physical space. After establishing that the mind and body are vitally necessary for each other and complement and complete each other, Iqbal goes further to show that the mental space, at least of the human self, is much larger in scope and capacity compared to the physical space of the same. Iqbal explains that the space and time of thought are different from those of the body. “My thought of space is in fact not spatially related to space”; while the body is in one space-time at any particular instance, the thought can act in different space-orders in that same instance. Therefore, the self is not space-bound in the same way as the body; it dwells in many worlds of its liking and is free to move about them. The self is not bounded in time either, firstly, because it remains intact in the flux of the experiences of the nafs, and secondly, because it persists even if the body perishes along with the experiences of the nafs. For Iqbal, “true time-duration belongs to the ego alone.”

The Quran unabashedly confirms that our ego, that oh-so-narcissistic part of ourselves, transcends both time and space. In fact, it’s so resilient that it can survive not one, but two rounds of lifelessness, and not to mention all the sins we’ve fessed up to. It’s almost as if it has a get-out-of-death-free card! This unity of the ego, or khudi, lies in its self-awareness and free-spirited, also known as ruh, which takes on one form of nafs while we’re on this rock we call Earth, but who knows what forms it may take in other cosmic settings. The possibilities are as infinite as the ego itself.

In conclusion, Iqbal’s perspective on the mind-body duality emphasizes the unity of the ego and its inseparable connection to the physical world. He rejects the idea of a passive soul or a mere illusion and seeks to establish the reality of the self as an undeniable entity. His views differ from those of the mutakallimun, who followed the Greek line of thought, and Ibn Rushd, who viewed the soul as a finer kind of matter or a mere accident.

Read more: