Hafiz Mudassar Naveed: The article is inspired from the views of Barrister Zameer Ghumro, who is an advisor of Republic Policy Think Tank.

A federation, by definition, is built when provinces or states come together to establish a cooperative system of governance. The federal structure is meant to distribute powers in a way that ensures collective handling of a few central subjects—such as defence, foreign policy, commerce, taxation, central banking, shipping and strategic highways—while leaving the larger share of responsibilities like education, health, policing, agriculture, local government and development to the provinces. Pakistan’s Constitution clearly embodies this principle, yet our federal practices increasingly betray it.

The National Finance Commission (NFC) Award is central to this arrangement. The 7th NFC, announced before the 18th Amendment in 2010, fixed the provinces’ share at 57.5 percent of tax revenue and the federal government’s at 42.5 percent. Even this formula tilted in favour of Islamabad because it excluded nearly Rs5 trillion in non-tax revenues that remain in the federal treasury. When both tax and non-tax collections are considered, the provinces barely receive 36 percent of available revenue, though they bear the heaviest governance burdens.

The centre’s budgetary behaviour has been fiscally reckless. For 2025–26, total federal expenditure is Rs17.5 trillion, of which Rs8.2 trillion goes to debt servicing and Rs2.5 trillion to defence. Civilian federal expenditure alone amounts to almost Rs7 trillion—an indefensible figure given the centre’s constitutionally limited responsibilities. A realistic ceiling would be Rs2.5 trillion, covering essential ministries, pensions, BISP, Gilgit-Baltistan and Kashmir. By trimming excesses, Islamabad could save Rs4 trillion annually—double the size of the IMF programme it repeatedly pursues.

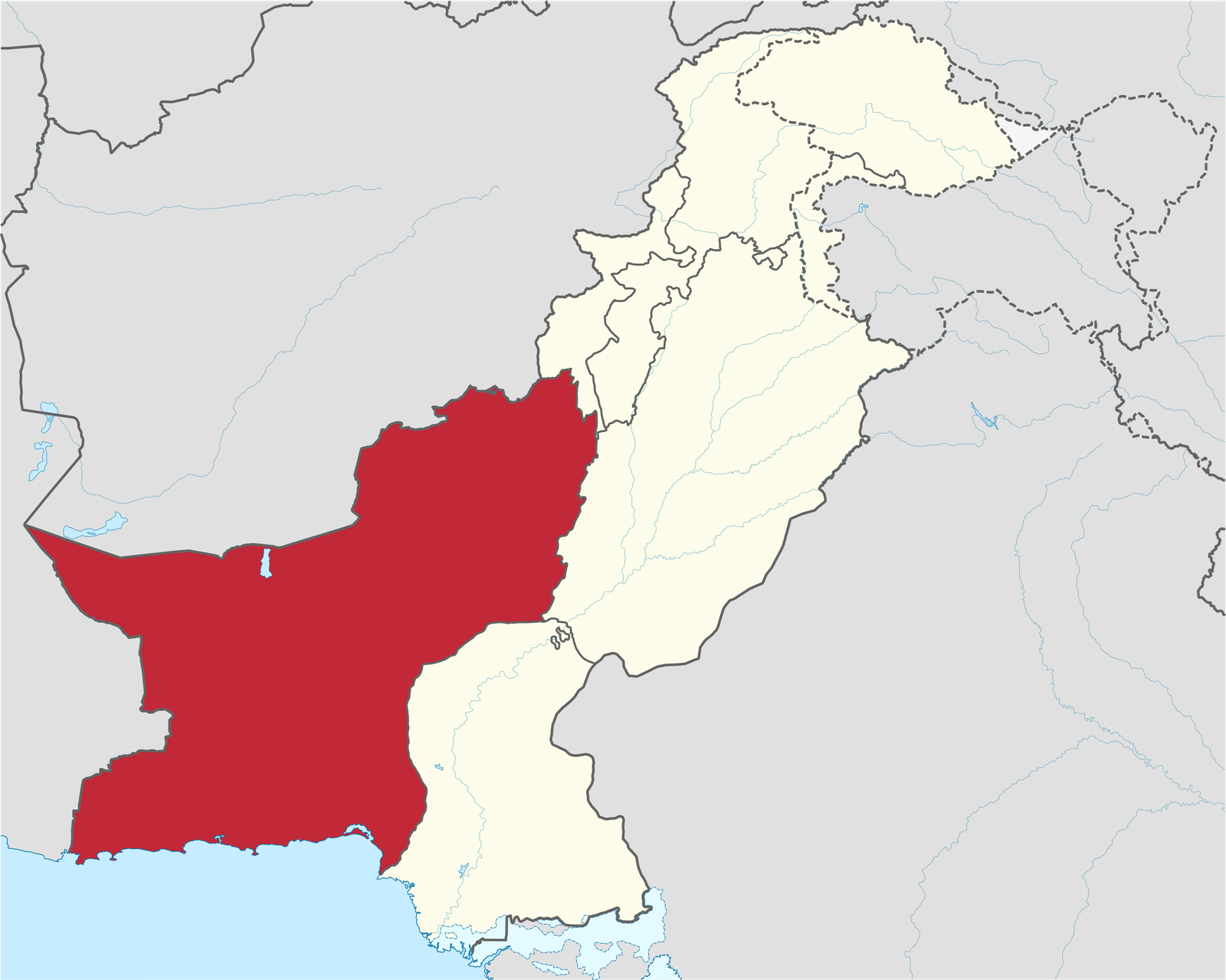

Instead, the federal government has expanded its footprint into provincial domains, borrowing excessively, sustaining duplicate ministries, and protecting an elite bureaucracy. The cost of this centralisation is immense: insurgency in Balochistan, unrest in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, resentment in Sindh, and alienation even within Punjab. Citizens see resources captured in Islamabad while provinces struggle with underfunded schools, collapsing hospitals and weak local governments.

The ongoing 11th NFC deliberations offer a decisive chance to reset fiscal federalism. Article 160 of the Constitution guarantees that provinces cannot receive less than their previous share. But the real test lies in recognising that provinces must receive a fair portion of both tax and non-tax revenues. Only then can they deliver on their constitutional obligations. A reallocation that reduces Islamabad’s civilian expenditure and ensures provinces retain at least half of the federation’s total revenue is essential for stability.

If Islamabad insists on maintaining its bloated structure, Pakistan’s financial crisis will deepen. The federal government’s non-developmental spending already outpaces the combined budgets of the four provinces, choking off development at the grassroots. This contradiction undermines the very idea of federalism and corrodes public trust in the union. A fair NFC formula, based on equity and constitutional clarity, is not optional—it is the lifeline of Pakistan’s federation.

The provinces created Pakistan in 1947 as a federation committed to welfare and justice. To honour that spirit, the NFC must prioritise people over bureaucracy, development over duplication, and fiscal responsibility over elite privilege. Only then can Pakistan’s federation survive and prosper.