Masood Khalid Khan

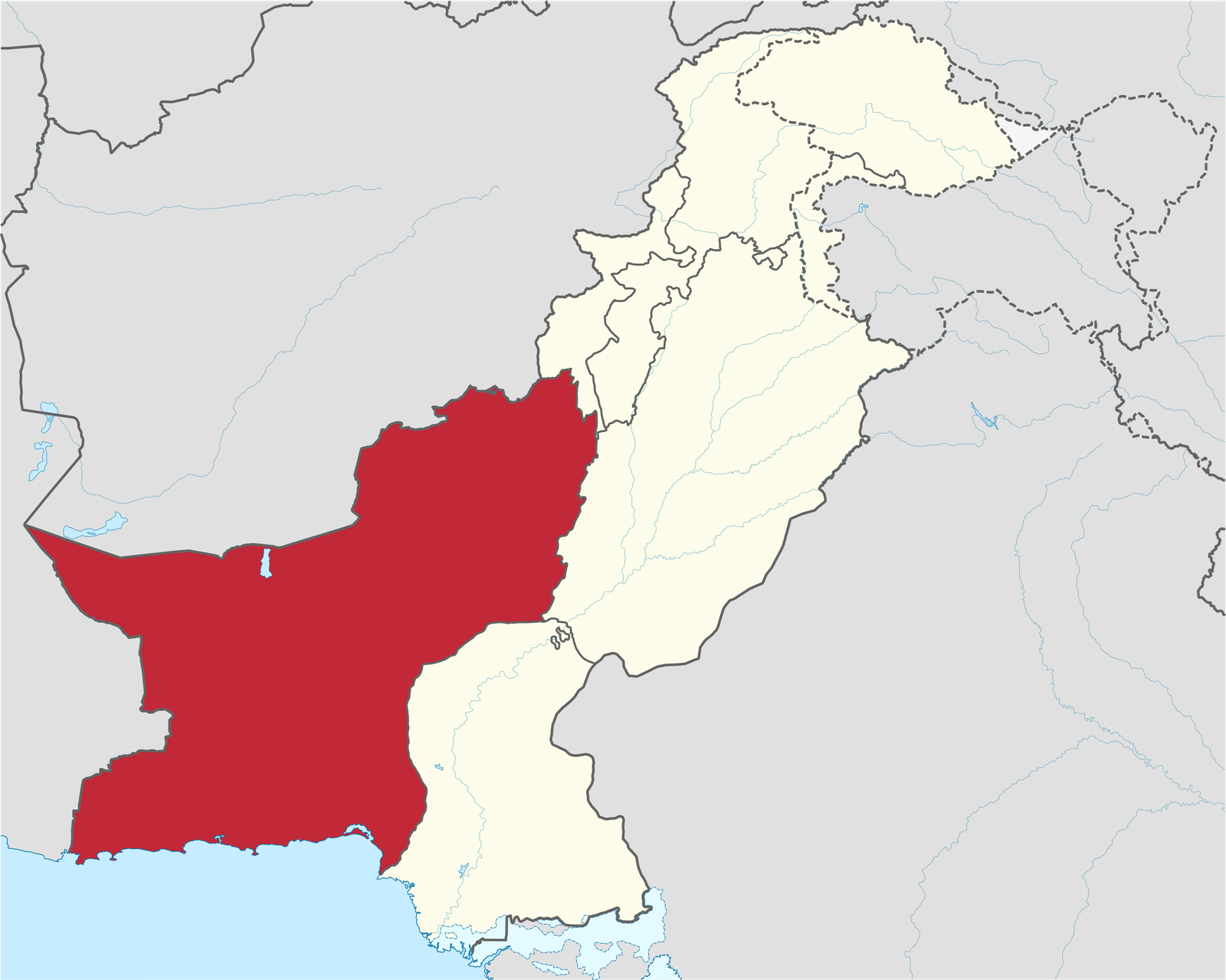

Pakistan’s troubled relationship with vaccination is once again shaping a critical public health decision. Sindh’s move to include the Human Papillomavirus vaccine in the Expanded Programme on Immunisation is medically sound and administratively sensible. Cervical cancer is largely preventable, and the vaccine has a strong global record of safety and effectiveness. Yet in Pakistan, scientific consensus alone has never been enough. The policy now enters a public space defined less by evidence and more by deep rooted suspicion of state led vaccination efforts.

This mistrust did not emerge overnight. It is the product of repeated failures to communicate clearly, listen to public concerns, and build credibility at the community level. In that context, the HPV vaccine should have been an uncontroversial addition to routine immunisation. Instead, it arrives carrying the baggage of a recent campaign that struggled to gain acceptance. That drive, which targeted girls between the ages of nine and fifteen, was met with resistance despite official assurances and a visible media push. False narratives, amplified through social media and AI generated videos, spread faster than factual explanations. For many parents, doubt overwhelmed trust, and refusal became the safer choice.

The lesson from that experience is not that the vaccine was wrong, but that the approach was incomplete. By embedding the HPV vaccine within the Expanded Programme on Immunisation, the Sindh government has taken a necessary corrective step. Routine immunisation programmes generally enjoy greater legitimacy than time bound campaigns. They are familiar, institutionalised, and perceived as part of standard healthcare rather than an exceptional intervention. Making the vaccine freely available at designated centres removes cost barriers and signals public responsibility. Allocating dedicated funding over three years adds continuity and reduces the perception of a rushed or experimental initiative.

These are important administrative strengths. They show intent, planning, and commitment. However, they do not address the deeper issue that continues to undermine vaccination efforts across Pakistan. Social hesitation does not disappear simply because a programme is formally approved. Rumour, mistrust, and fear have repeatedly proven more powerful than official notifications or press briefings.

Vaccination in Pakistan has long been vulnerable to misinformation. Decades of polio related conspiracy theories, foreign interference narratives, and poorly handled campaigns have left scars on public confidence. In this environment, trust cannot be manufactured through advertising alone. Nor can it be enforced through bureaucratic authority. It must be built patiently and locally, through sustained engagement with the communities most affected.

This makes the challenge fundamentally political, though not in the narrow sense of party politics. It is about the relationship between the state and citizens. Parents need to be confident that the vaccine is safe, properly monitored, and genuinely intended to protect their children. They need to see healthcare workers who are informed, empathetic, and able to answer difficult questions without dismissiveness. They need reassurance from trusted local figures, not just distant officials or televised experts.

Misinformation cannot be countered only after it spreads. It has to be anticipated. That requires early engagement with teachers, community elders, religious leaders, and local health workers who already hold social credibility. It requires transparency about side effects, monitoring mechanisms, and accountability if problems arise. Silence or vague assurances only create space for false narratives to grow.

The inclusion of the HPV vaccine in the EPI is a necessary policy decision, but it is not a complete solution. Without parallel investment in trust building, the programme risks repeating the mistakes of the past. Public health success depends not just on vaccines, funding, and logistics, but on belief. When people feel excluded from decision making, they fill the gap with suspicion.

If Sindh, and Pakistan more broadly, wants this initiative to succeed, it must treat trust as a core component of immunisation policy, not an afterthought. Cervical cancer prevention is a public good. But public goods require public confidence. Without it, even the most medically sound interventions struggle to take root.