Naveed Akhtar Rana

Relations between Pakistan and Bangladesh, long overshadowed by the tragic events of 1971 and the difficult legacy of Sheikh Hasina Wajed’s government, are witnessing a rare thaw. For over a decade, Dhaka had maintained a firm distance from Islamabad, often echoing India’s rhetoric in regional politics. However, with the arrival of Bangladesh’s interim administration, the political temperature appears to have cooled, making way for fresh opportunities of dialogue and partnership.

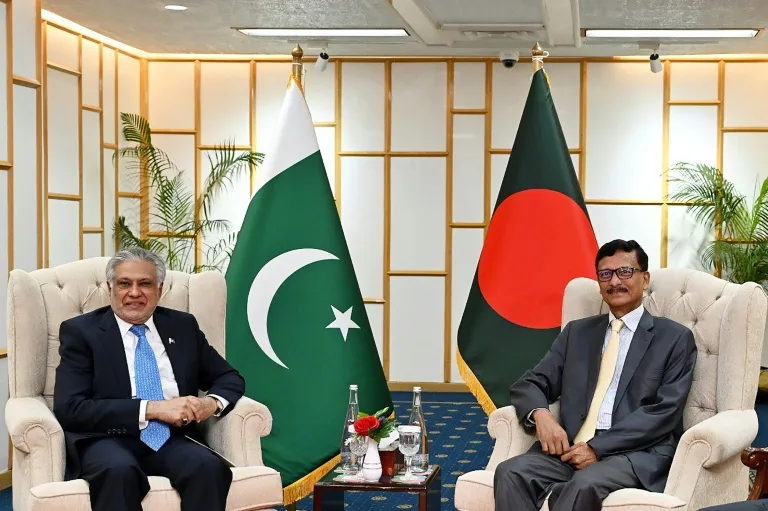

The turning point came with Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar’s official visit to Dhaka — the first such high-level trip by a Pakistani foreign minister in 13 years. The visit was marked by a warm welcome, the signing of six cooperation agreements across multiple sectors, and significant gestures of goodwill from Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus and Bangladesh’s foreign affairs adviser. Both sides not only expressed an interest in rebuilding ties but also raised the possibility of reviving Saarc, a regional forum that has remained frozen due to Indo-Pak hostility. The issue of 1971 inevitably surfaced, yet the tone was markedly different from the years of bitterness under Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League government.

For decades, Sheikh Hasina’s administration used the 1971 separation of East Pakistan and the violent war of liberation as a political tool to keep hostility towards Pakistan alive. She built close ties with India, aligning Dhaka’s foreign policy firmly with New Delhi’s priorities. Pakistan, in turn, maintained that the question of an apology or reparations had already been settled with its recognition of Bangladesh in 1974 and General Pervez Musharraf’s expression of regret during his 2002 visit. Despite these overtures, Hasina’s regime repeatedly invoked the past to justify political persecution at home and diplomatic friction abroad.

Republic Policy on X (Twitter)

However, Bangladesh’s political landscape has changed dramatically since the Awami League’s ouster. Statues of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman have been attacked, institutions bearing his name have faced public wrath, and even his portrait has been removed from Bangladeshi currency. These shifts suggest that the once unassailable cult of ‘Bangabandhu’ is losing ground. The backlash is rooted in the widespread perception that Sheikh Hasina had monopolized national history and weaponized it to crush opposition, leaving deep scars on Bangladesh’s democratic institutions. The interim government’s decision to move away from this personality-driven politics has created space for more pragmatic engagement with Pakistan.

While both Islamabad and Dhaka continue to differ on how the 1971 tragedy should be remembered, it is vital that this sensitive issue not become a permanent stumbling block. Nations do not progress by remaining imprisoned in history; rather, they move forward by acknowledging differences while building on shared interests. The Pakistani argument that recognition and regret have already addressed past grievances carries weight. At the same time, Pakistan should remain open to symbolic gestures of reconciliation that do not compromise its dignity but allow Bangladesh to heal.

The revival of Saarc, though raised during Ishaq Dar’s visit, remains a distant dream so long as India continues to obstruct regional cooperation. Yet, Pakistan and Bangladesh need not wait for India’s consent to work together. A more practical alternative exists in the trilateral cooperation forum with China, which could be expanded into a broader framework of regional economic connectivity. Trade corridors, energy cooperation, and joint technology projects between Pakistan, Bangladesh, and China could pave the way for an Asian development bloc independent of New Delhi’s veto.

Pakistan and Bangladesh share cultural, linguistic, and historical ties that transcend the bitterness of 1971. Millions of Pakistanis trace roots to Bengal, while millions of Bangladeshis acknowledge that their shared Muslim heritage binds them to South Asia’s wider Islamic identity. More importantly, both countries confront similar challenges: climate change, food insecurity, energy shortages, and economic volatility. By working together, they can not only strengthen bilateral trade but also amplify their collective bargaining power on global platforms.

Republic Policy WhatsApp Channel

Looking ahead, the real test will come with Bangladesh’s next elected government. Will it continue the interim administration’s reconciliatory approach, or will it revert to the divisive politics of Sheikh Hasina’s era? For Pakistan, the strategy must be consistent: offer partnership in trade, education, climate adaptation, and cultural exchanges, while carefully avoiding inflammatory rhetoric about 1971. Diplomacy must emphasize the promise of a shared future rather than the shadows of a fractured past.

In conclusion, Pakistan and Bangladesh now stand at a crossroads. The hostility of the past need not define the possibilities of the future. With new political realities in Dhaka, Islamabad has an opportunity to reset ties and explore avenues for cooperation beyond Saarc. Both nations must embrace reconciliation not as a denial of history but as an affirmation of their shared destiny. By doing so, they can transform decades of mistrust into a partnership for regional peace and prosperity.