Mubashir Nadeem

In a world dominated by headlines of conflict, economic hardship, and political instability, rare are the stories from Pakistan that truly inspire and uplift — stories that transcend national borders and capture global admiration. One such extraordinary narrative is that of Sirbaz Khan, a mountaineer from the Hunza Valley in Gilgit-Baltistan, who has achieved something almost superhuman: he has become the first Pakistani — and one of fewer than 25 people globally — to climb all 14 of the world’s 8,000-metre peaks without using supplemental oxygen. This is not just a personal victory for Sirbaz; it is a national milestone for Pakistan, which has long lacked recognition in the global mountaineering community.

Sirbaz completed this monumental feat on May 18, 2025, when he summited Mount Kanchenjunga in Nepal, the world’s third-highest mountain standing at 8,586 metres. While he had already conquered all 14 of the world’s highest peaks in earlier expeditions, he had used bottled oxygen on two of those ascents. To meet the highest international standard of climbing — no oxygen in the ‘death zone’ above 8,000 metres — he returned to scale Annapurna in April and Kanchenjunga in May, both without artificial oxygen.

To put this achievement into perspective, the “death zone” is not just a metaphor. At altitudes above 8,000 metres, oxygen levels are so low that the human body begins to shut down. The environment is brutally unforgiving. Even with the best gear and physical conditioning, most climbers require supplemental oxygen to survive — let alone to perform a technical ascent. Sirbaz’s success, therefore, speaks volumes about his mental tenacity, physical endurance, and spiritual resolve.

Sirbaz’s journey began in 2017, when he successfully summited Nanga Parbat, one of the most dangerous mountains in the world. From there, he methodically took on some of the most perilous and celebrated peaks, often venturing where few have dared. He conquered K2 in July 2018 — the second-highest and arguably the deadliest mountain on Earth. In 2019, he scaled Lhotse and Manaslu, becoming the first and second Pakistani, respectively, to accomplish those feats.

His reputation grew with each ascent. In April 2021, Sirbaz became the first Pakistani to summit Annapurna, one of the world’s most lethal peaks due to its frequent avalanches and treacherous weather. Just a month later, he stood atop Mount Everest, the roof of the world. And with the summit of Shishapangma on October 4, 2024, Sirbaz officially completed his 14-peak conquest.

Yet what makes his journey even more remarkable is that he refused to stop at just ticking off names on a list. For Sirbaz, climbing was never about glory for its own sake; it was about setting a new standard. That meant returning to the mountains he had already conquered — and doing it again, this time without oxygen, in conditions that challenge even the most elite climbers in the world.

In a country where cricket dominates the sporting landscape, accomplishments in disciplines like mountaineering rarely get the recognition they deserve. Sirbaz Khan has scaled greater physical heights than perhaps any other Pakistani athlete in history, yet his name is still not widely known. Unlike Western climbers who often receive brand sponsorships, media coverage, and state honors, Sirbaz has accomplished his feats in relative obscurity and without the kind of institutional support that might be expected for someone of his calibre.

This disconnect between his accomplishments and public recognition reflects a broader issue in Pakistan’s sports policy: the lack of systemic investment in non-mainstream disciplines. Mountain climbing is still treated as a fringe activity. There is no national climbing federation with adequate resources, no structured sponsorship program, and very little government interest in promoting the sport as a professional pursuit.

This is a missed opportunity. Sirbaz’s story, and that of fellow climbers like Naila Kiani, who last year became the first Pakistani woman to summit 11 of the 8000-metre peaks, shows that Pakistan has the talent — what it lacks is support. With the right infrastructure, financial backing, and media attention, Pakistan could not only produce more world-class climbers but also position itself as a premier destination for high-altitude tourism.

Beyond sports, Sirbaz’s ascent is metaphorically rich for a nation that often feels trapped by circumstances. Pakistan is a country familiar with adversity, whether political, economic, or environmental. Sirbaz’s ability to push past every imaginable limit — to climb into the thin, suffocating air where human life can barely survive — mirrors the kind of grit and resolve that countless ordinary Pakistanis demonstrate every day.

His journey offers a new kind of national role model. Not one born of political charisma or financial power, but forged through quiet perseverance, strategic thinking, and extreme discipline. In an age where superficial influencers dominate headlines, Sirbaz’s life reminds us of the enduring power of humility, focus, and action.

Sirbaz Khan’s success should not remain a solitary footnote in the annals of Pakistani sports history. It should trigger a national conversation about how we define success, how we celebrate our heroes, and how we support emerging talent. The mountains of Pakistan are among the tallest and most spectacular in the world, yet they remain underutilized assets in both our sporting and tourism narratives.

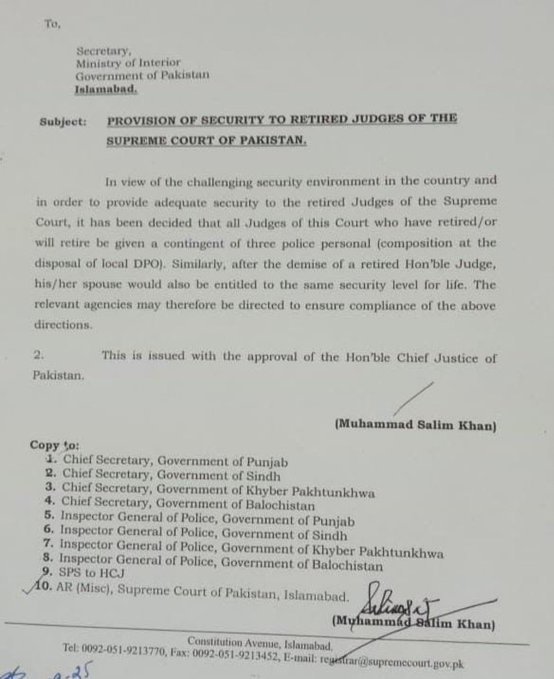

The time has come for Pakistan to institutionalize support for mountaineering. This means creating climbing academies, offering scholarships and grants, investing in safety and rescue infrastructure, and integrating outdoor sports into national youth development policies. Tourism ministries should also collaborate with local climbers to promote sustainable adventure tourism, which could help boost the economy in underserved regions like Gilgit-Baltistan.

Additionally, media and civil society should play a greater role in giving climbers like Sirbaz the recognition they deserve. National awards, documentary coverage, and educational outreach can help embed stories like his into the public imagination.

Sirbaz Khan has not just planted a flag on the world’s highest mountains; he has planted hope in the hearts of millions of Pakistanis. He has shown that excellence is not confined by borders, budgets, or even oxygen.

His achievement is a towering reminder of what unwavering commitment can yield — even in a country that offers little by way of institutional support. It is now up to policymakers, sports federations, and civil society to carry his legacy forward and ensure that he is the first, but not the last, Pakistani to climb into the rarefied air of greatness.

If Pakistan can learn to value its silent heroes, it may yet find a path to a more elevated future.