Editorial

In every democracy, the role of parliament is critical: it is the forum where national decisions are deliberated, debated, and sanctioned, it is the mechanism by which the will of the people, expressed through their representatives, is translated into policy; in a parliamentary democracy, this process becomes even more central, for the essence of parliamentary governance is that decisions of national and international significance pass through the collective wisdom of the house, that they are not determined solely by the executive, and that they are exposed to the scrutiny of a body that embodies the electorate. This has been the practice in countries with mature democracies, this has been the norm, and this adherence has been the very cause of parliamentary democracy thriving in its true essence. A parliamentary democracy, by design, is meant to balance power, restrain unilateral action, and ensure that decisions, particularly those of strategic importance, are taken with consensus and deliberation.

However, when it comes to Pakistan, these concepts have rarely been implemented according to their design; rather, they have been interpreted and executed according to the preferences, ambitions, or convenience of those in power. The de jure framework of parliamentary democracy exists: Pakistan has a National Assembly, a Senate, committees, opposition benches, and constitutional provisions that define procedures and responsibilities; yet, de facto, these institutions have consistently been compromised. From the inception of the country’s political system, decisions of immense national and international consequence have been taken without meaningful parliamentary involvement; the executive, often acting alone, has defined the scope, timing, and communication of such decisions, leaving parliament as a passive observer rather than an active participant.

The practice, over decades, has entrenched a culture of unilateral decision-making in matters that ought to be subject to debate. Military interventions in foreign conflicts, international treaties, defense agreements, foreign loans, and the deployment of forces abroad are all examples where parliamentary oversight has been minimal or entirely absent. The rationale presented in each case often rests on urgency or secrecy, yet the cumulative effect is that parliamentary democracy is reduced to a ceremonial framework, an institutional façade that cannot exercise its true authority. The very essence of accountability, the capacity to question, the responsibility to weigh benefits against risks, becomes lost.

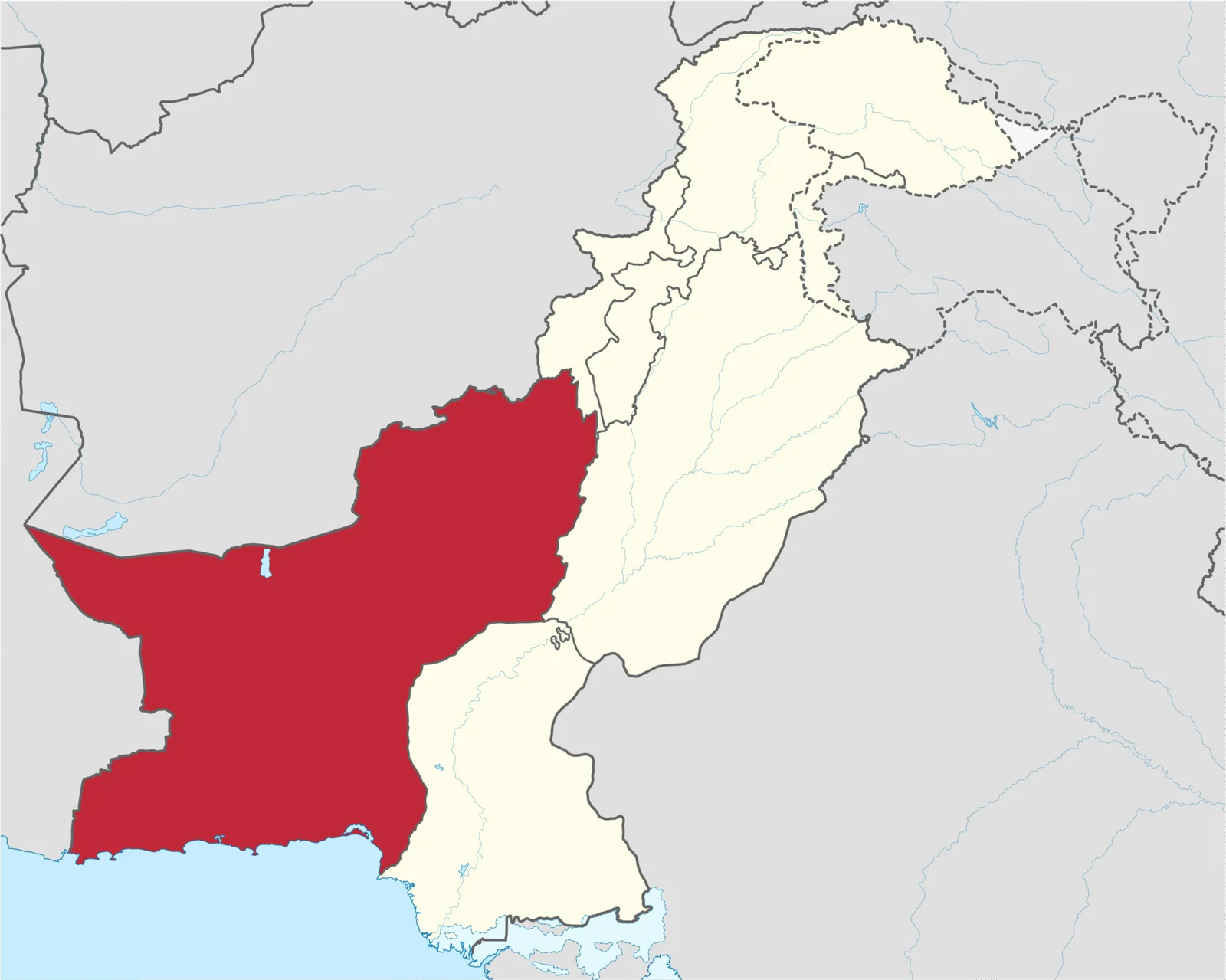

A case in point, recent and illustrative, is Pakistan’s decision to send its forces to Gaza under the framework of the US-led “Board of Peace.” Regardless of the nature of the deployment, the terms, or the conditions, this decision carries profound international implications. It involves Pakistan’s military posture abroad, its diplomatic positioning in the Middle East, the management of relations with Arab states, Israel, and the United States, and the perception of Pakistan in the eyes of its own citizens. In every country that practices parliamentary democracy seriously, such a decision would demand prior discussion in the house, debate among political parties, committee oversight, and at least a formal approval or rejection by elected representatives. In Pakistan, however, the decision was announced and implemented without parliamentary debate, without formal consultation with opposition benches, and without a clear public rationale communicated to the citizenry.

This absence of debate is consequential: as long as decisions succeed, as long as there are no immediate or visible negative repercussions, the silence is tolerated, the lack of scrutiny overlooked, and the process accepted by default. Success validates the method; the public rarely asks how or why, for tangible results overshadow procedural neglect. Yet the moment a decision encounters difficulties, unforeseen complications, or international criticism, the same unilateral approach becomes a source of contention. The blame shifts rapidly, the discourse turns acrimonious, and the very same actors who permitted unilateral action now demand accountability, yet fail to acknowledge the structural problem: decisions of international consequence should never have bypassed parliamentary oversight.

It is not simply a question of protocol; it is a matter of principle. Parliament is not merely an assembly of symbolic representatives; it is the guarantor of the social contract, the arena where the diverse interests, perspectives, and priorities of the nation converge. A decision on foreign military deployment, for instance, impacts domestic politics, affects resource allocation, and shapes Pakistan’s international reputation. It carries strategic risks, including retaliation, diplomatic pressure, and alignment challenges with allies and adversaries alike. Such risks require collective evaluation, diverse expertise, and open debate, all of which are functions of a robust parliamentary system. The repeated bypassing of these mechanisms erodes the credibility of governance and undermines public trust.

In the broader context, Pakistan’s political history offers many examples where executive-driven decisions, taken without parliamentary input, have created long-term complications. Agreements with international financial institutions, decisions to join regional coalitions, arms procurement, and treaties with neighboring countries have frequently been presented to parliament post facto. The public, confronted with pre-packaged policies, has little opportunity to understand, influence, or challenge the reasoning behind them. This creates a pattern: the executive assumes authority by default, parliament is sidelined, and the principle of collective accountability is weakened.

It is important to understand that the issue is not merely procedural; it has profound political and societal implications. A parliamentary system functions optimally when parties, opposition and government alike, contribute to shaping national policy. It fosters transparency, encourages negotiation, and reduces polarization, for decisions taken collectively are harder to politicize. In Pakistan, the absence of such deliberation allows not only executive overreach but also opportunistic politicization. Every challenge or failure becomes a matter of blame, a point of political contention, rather than a subject for collective reflection and adjustment.

The decision regarding Gaza highlights the urgency of this gap. By sending forces without parliamentary debate, Pakistan signals a willingness to engage in international conflicts while limiting domestic accountability. Such an approach may temporarily streamline decision-making, yet it exposes the country to criticism from political factions, civil society, and the international community. It raises questions about sovereignty, representation, and the legitimacy of decision-making, especially when the deployment has humanitarian, diplomatic, and strategic consequences. Parliament, in theory, should serve as the arena where these questions are rigorously examined; by excluding it, the decision-making process remains incomplete.

Moreover, bypassing parliament sets a dangerous precedent. If future decisions follow the same pattern, the democratic process becomes progressively hollowed out. The distinction between a parliamentary democracy in name and one in practice grows wider, with consequences that ripple across governance, civic engagement, and institutional trust. Citizens, observing a pattern of unilateral action, may become disengaged, perceiving their elected representatives as irrelevant to matters that shape the nation’s destiny. Political parties, meanwhile, may exploit the vacuum for partisan advantage rather than engaging constructively in oversight.

There is a simple remedy: restore the centrality of parliament in decisions of national and international importance. Strategic and foreign policy choices should be tabled for discussion, committees should evaluate risks and implications, opposition parties should be engaged, and public communication should ensure transparency. Such measures do not weaken executive authority; rather, they strengthen legitimacy, reinforce democratic norms, and distribute responsibility across the polity. By embedding parliamentary consultation into the decision-making process, Pakistan can bridge the gap between the principle and practice of democracy.

Ultimately, the lesson is clear. Pakistan has a parliamentary system in design, but the lived reality has often diverged from the ideal. Decisions of international consequence, like the deployment of forces to Gaza, must not be left solely to the executive; they demand deliberation, debate, and consent of parliament. Successes taken unilaterally may go unchallenged, yet failures carry immediate and intense criticism. To prevent this cycle, to protect both governance and credibility, parliamentary democracy must be more than a formal structure; it must be the active engine driving national decisions, ensuring that authority is exercised responsibly, transparently, and collectively.

Parliament is not a mere formality; it is the core of democratic governance. By restoring its central role in national decisions, Pakistan can move toward a political culture where international engagements are managed with wisdom, inclusivity, and accountability. Only then can parliamentary democracy in Pakistan be said to operate in its true essence: a system where the nation decides together, and where the people, through their elected representatives, participate fully in shaping the country’s path.