Arshad Mahmood Awan

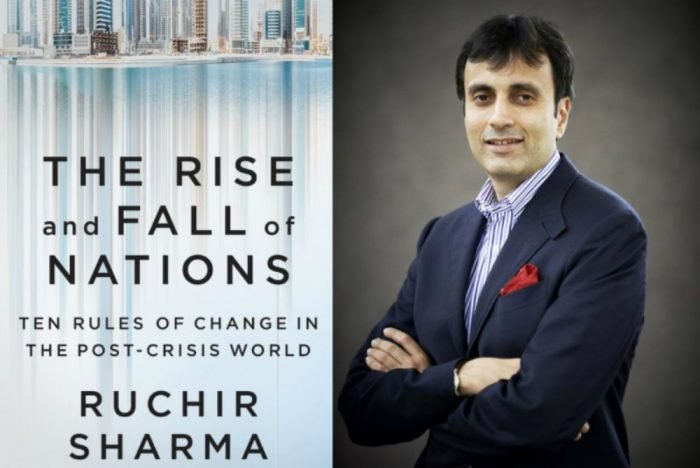

The book The Rise and Fall of Nations by Ruchir Sharma is a guide to understanding the global economy and the factors that shape the fortunes of different countries. Sharma identifies ten clear rules that can help investors, policymakers and analysts to spot the signs of economic booms and busts, as well as the social and political changes that affect them. The book covers various topics such as population growth, current account deficits, currency values, private debt, political leadership, corruption, inequality, urbanization, innovation and geography. The book is based on Sharma’s extensive travels and encounters with people from different walks of life, as well as his analysis of data and trends. The book aims to provide a practical and entertaining field guide to understanding change in this era or any era.

The present fall of Pakistani institutions is a result of multiple sources of internal and external conflict that have plagued the country for decades. Pakistan faces challenges such as extremism, intolerance, polarization, violence, terrorism, corruption, poverty, inequality, climate disasters, governance failures, economic instability and regional tensions. These challenges have eroded the trust and legitimacy of state institutions such as the judiciary, the parliament, the executive, the bureaucracy, the police and the military. The inability of these institutions to reliably provide peaceful ways to resolve grievances has encouraged groups to seek violence as an alternative. The country has also witnessed frequent political crises and transitions that have disrupted its development and stability. There is a conflict on the form of governance as well as who should elect the government, either by the people or other powerful institutions. Then, political conflict is directly influencing the governmental system as well as common Pakistanis.

A comparative analysis between the book and the present situation in Pakistan can reveal some similarities and differences. On one hand, some of the rules that Sharma proposes in his book can be applied to understand Pakistan’s economic performance and potential. For example, Sharma argues that population growth is a key driver of economic growth and that countries with young and growing populations have an advantage over those with ageing and shrinking populations. Pakistan has one of the youngest and fastest-growing populations in the world, which can be a source of demographic dividend if properly harnessed through education, employment and empowerment. However, Sharma also warns that population growth can be a curse if it is not accompanied by adequate investment in human capital and social services. Pakistan faces challenges such as low literacy rates, high maternal and child mortality rates, poor health care access and quality, gender discrimination and violence. Therefore, population growth is a matter of instability in Pakistan due to lower capacity and human resource indicators.

Another rule that Sharma suggests is that current account deficits are a sign of economic vulnerability and that countries that rely on foreign borrowing or aid to finance their imports are more prone to crises than those that export more than they import. Pakistan has been running persistent current account deficits for years, which have depleted its foreign reserves and increased its external debt. Pakistan has also been dependent on foreign aid and loans from various sources such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), China, Saudi Arabia and others to support its economy. Sharma argues that countries that have large current account deficits are more likely to face currency devaluation, inflation, capital flight and social unrest.

On the other hand, some of the rules that Sharma proposes in his book may not be applicable or relevant to Pakistan’s situation. For instance, Sharma claims that political leadership is a crucial factor in determining a country’s economic success or failure and that leaders who are decisive, pragmatic and visionary can make a difference in steering their countries towards prosperity or decline. He also argues that leaders who stay in power for too long tend to become complacent, arrogant and corrupt. However, Pakistan’s experience shows that political leadership alone is not sufficient or decisive in shaping its economic destiny. Pakistan has had various types of leaders over its history, ranging from democratically elected civilians to military dictators to technocrats. None of them have been able to overcome the structural constraints and challenges that Pakistan faces in terms of its institutional capacity, social cohesion, security environment and regional dynamics.

Another rule that Sharma advocates is that innovation is a key driver of economic growth and that countries that invest in research and development (R&D), education, technology and entrepreneurship are more likely to achieve higher productivity and competitiveness than those that rely on natural resources or cheap labour. He also suggests that countries should diversify their economies away from dependence on a few sectors or commodities1. However, Pakistan’s reality shows that innovation alone is not enough or feasible without addressing other factors such as infrastructure, governance, security and social inclusion. Pakistan has a low level of investment in R&D (less than 0.3% of GDP), a low quality of education (ranked 152 out of 189 countries by UNESCO), a low level of technological adoption (ranked 110 out of 141 countries by the World Economic Forum) and a low level of entrepreneurial activity (ranked 108 out of 137 countries by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor). Pakistan also faces challenges such as power shortages, corruption, terrorism, extremism and discrimination that hinder its innovation potential. Because Pakistan has yet to reform structurally, different standards of development and growth are mostly irrelevant.

Lastly, a comparative analysis between the book The Rise and Fall of Nations and the present fall of Pakistani institutions can provide some insights and lessons for understanding Pakistan’s economic prospects and challenges. However, it can also reveal some limitations and gaps in applying a universal or general framework to a specific or complex context. Pakistan’s situation is influenced by a multitude of factors that are not easily captured or measured by a set of rules or indicators. Therefore, a more nuanced and contextualized approach is needed to address Pakistan’s problems and opportunities. However, whatever the circumstances and applications are, Pakistan must reform structurally and institutionally.

Please, subscribe to the YouTube channel of republicpolicy.com