Mudassir Rizwan

In the wake of the fall of the Assad regime in Syria, there has been an outpouring of optimism from Western and Middle Eastern capitals, with many commentators believing that peace and stability in the Levant are finally within reach. The end of the Baathist dynasty, which had ruled Syria for over half a century, was seen by some as the closure of a dark chapter in the region’s history. However, those celebrating this development may be in for some unpleasant surprises, as the road ahead remains fraught with challenges, many of which are yet to be fully understood.

One of the most significant developments in the aftermath of Assad’s fall is the rise of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a militant group that suddenly appeared on the scene and swiftly dismantled a regime that had been in power for over fifty years. HTS, which can be traced back to the infamous al-Nusra Front, an al-Qaeda affiliate, is the latest incarnation of a group that has long been funded and supported by Western, EU, Gulf, and Turkish powers. What remains largely unexamined in the current celebration is how Abu Mohammad al-Golani, the leader of HTS, emerged from obscurity. A former al-Qaeda commander who spent years in a U.S. prison in Iraq, Golani now commands a group that has received support from powerful intelligence agencies, likely from the West. This raises questions about the underlying geopolitical forces at play, with many wondering how a group with such a dark history gained so much traction and support.

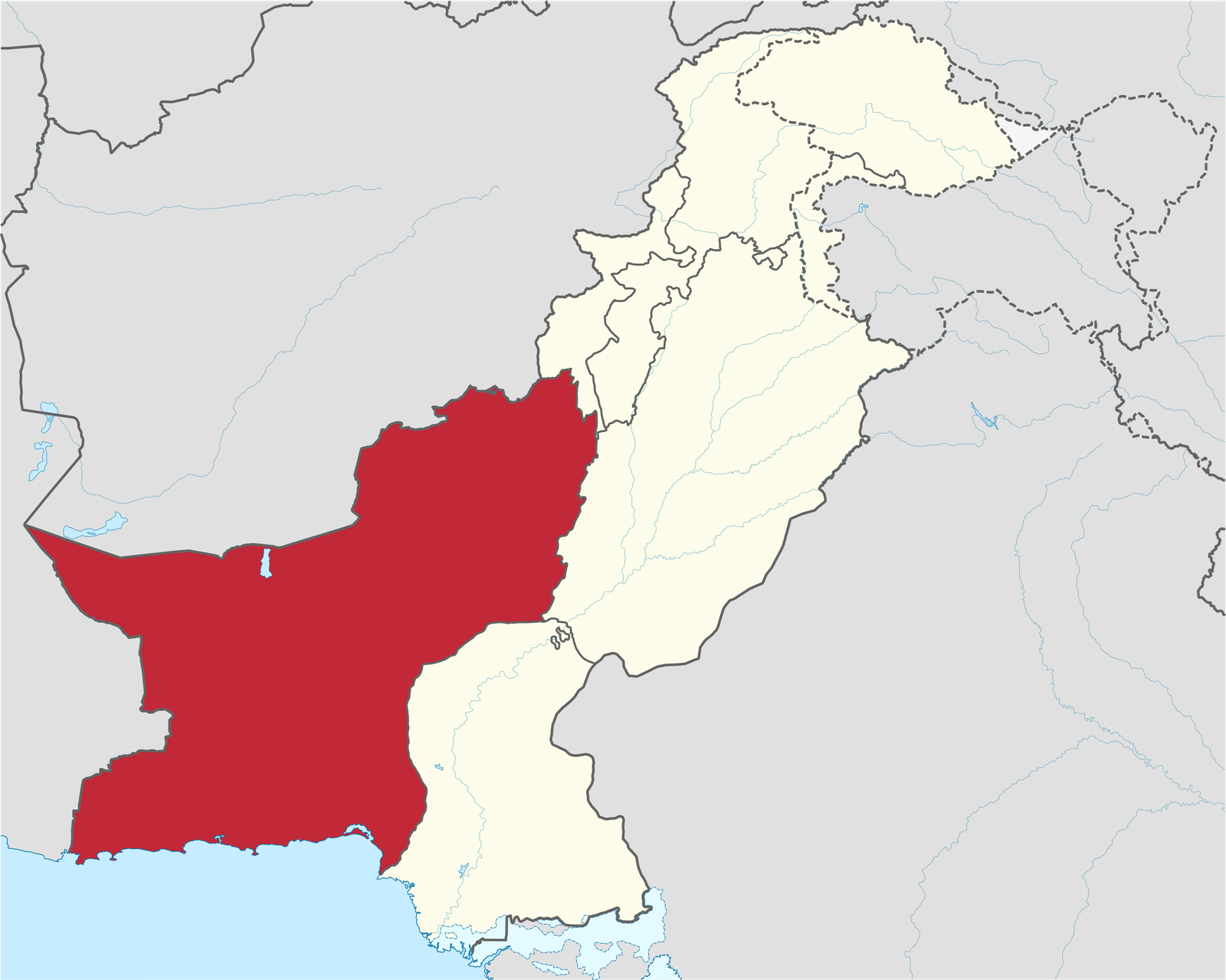

The military and logistical backing of HTS, which played a crucial role in the downfall of the Assad regime, is not in question. The timing of their success, coinciding with Israeli and U.S. efforts to curb Iranian influence in the region, further underscores the complexity of the situation. While it is clear that Iran’s influence in Syria has been significantly diminished, its militias neutralized, and its presence in the Mediterranean severely curtailed, this is only part of the story. Western powers, Israel, and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) have reason to celebrate the weakening of Iran’s position, but this does not guarantee that the post-Assad future will be any easier or more stable.

Despite the apparent shift in HTS’s rhetoric, with Golani presenting himself as a peacemaker who forbids his forces from engaging in sectarian violence or revenge, the group’s history and membership remain troubling. HTS’s rank and file consists of the same extremist forces that have caused devastation across the region in recent years, from Iraq to Libya. These fighters, notorious for their brutality, have not suddenly transformed into benevolent peacekeepers. The Western media may paint Golani as a reformed leader, but his group’s underlying ideology and violent history cannot be easily dismissed. HTS’s previous actions, such as the targeting of religious minorities and sectarian violence, should not be forgotten, and their true intentions remain suspect.

In this context, the United States has announced that it will continue to monitor developments in Syria closely, particularly as the country transitions to a new government. The U.S. and other external powers will inevitably seek to influence the political landscape, ensuring that their interests are protected in the post-Assad era. But such interventions will come with their own set of complications. Countries like Turkey and the GCC have long been positioning themselves to play a major role in Syria’s future. Turkey, in particular, has been an active player in the conflict since its onset, and its influence over the future of Syria cannot be underestimated. The Gulf States, too, are eager to secure their interests, particularly in relation to Iran’s diminished presence.

However, it is important to remember that the downfall of Bashar al-Assad was not solely the result of external forces. While the Assad regime received significant support from Russia and Iran during the civil war, the regime had already been weakened internally long before outside intervention played a decisive role. The Syrian military, much like the government itself, had been hollowed out over the years. The lack of internal cohesion, combined with the regime’s increasing reliance on foreign support, left Assad vulnerable when both Russia and Iran became preoccupied with other conflicts. When these powers were distracted by other geopolitical crises, Damascus crumbled with astonishing speed.

Bashar al-Assad’s ability to avoid the fate of other Arab dictators, such as Muammar Gaddafi of Libya or Saddam Hussein of Iraq, may have been due to his political acumen. He skillfully navigated the complexities of international diplomacy and managed to survive in power for as long as he did. However, the real question is whether Assad’s Alawite community will be spared from the sectarian violence that has already swept through much of the Middle East. As seen in Iraq and Libya, when regimes fall, the resulting power vacuums often lead to brutal sectarian conflicts. With so much hatred and resentment already entrenched in Syrian society, there is a real risk that Assad’s sect, the Alawites, could become the targets of revenge once the dust settles.

Furthermore, Bashar al-Assad’s rule was marked by brutality and oppression. While there was initially hope that he might be a reformer when he succeeded his father, Hafez al-Assad, in 2000, his presidency quickly became characterized by violence, corruption, and widespread human rights abuses. His regime was more repressive and unjust than those of many of his counterparts in the Arab world, including Gaddafi, Ali Abdullah Saleh of Yemen, and Hosni Mubarak of Egypt. Assad’s government cracked down mercilessly on dissent, and the brutality with which the regime responded to the Arab Spring protests in 2011 marked the beginning of the Syrian civil war. What followed was a devastating conflict that displaced millions and left the country in ruins.

In conclusion, while the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime may be seen as a victory for many, the future of Syria remains uncertain. The rise of HTS and the shifting power dynamics in the region signal that the country’s problems are far from over. The involvement of external powers, the risks of sectarian violence, and the legacy of Assad’s oppressive rule all contribute to the complexity of the situation. It is crucial to understand that the fall of Assad does not necessarily mean the beginning of peace and stability for Syria. Rather, it may be the beginning of a new set of challenges that will require careful navigation and international cooperation to address. The hope for a peaceful and prosperous Syria remains distant, and the road to rebuilding the country will be long and fraught with difficulties.