Zohaib Tariq

The Mongol conquests of the 13th century under Genghis Khan and his successors were defined by a brutal clarity of purpose: rapid, overwhelming campaigns of military force; psychological domination; and a transactional relationship with conquered peoples in which submission was preferred over annihilation, but fear was the principal means of securing obedience. Mounted on horses with unmatched mobility, Mongol armies struck with lightning speed across Eurasia, not to settle and govern every conquered province personally, but to enforce compliance, extract tribute, and secure strategic advantage. Their authority did not rest on law or shared norms—there was no broader civilizational order they were obliged to respect—but on might and the perception that resistance was futile.

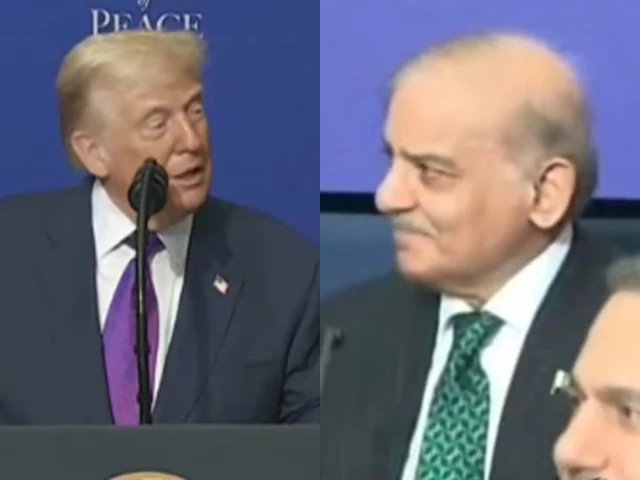

Fast forward to the present, and a strikingly similar logic seems to animate the foreign policy of the Trump administration in its second term, even if the form of coercion has shifted from steppe cavalry to missile strikes and special operations. In a widely reported interview with the New York Times, President Donald Trump explicitly dismissed international law as a meaningful constraint, stating that only his “own morality” limits his global actions and that he “doesn’t need international law” to guide U.S. conduct abroad, even as he contemplates further military interventions and territorial ambitions.

The U.S. operation in Venezuela, which involved a pre-dawn military strike on Caracas, the capture of President Nicolás Maduro, and his subsequent arraignment in New York, represents a watershed moment in this worldview—an unmistakable echo of steppe imperatives adapted to the 21st century. The administration’s posture frames militarized intervention not as a last resort under a system of international norms, but as an instrument of order and psychological pressure. Much like the Mongols made examples of cities that resisted to encourage capitulation elsewhere, the Venezuelan operation has been followed by open talk of similar actions against Colombia, Mexico, Cuba, Iran, and even the semi-autonomous Greenland—territories that, under traditional international law, are protected from external coercion.

This theory of power—where the legitimacy of use of force flows not from treaties or consensual norms, but from the ruler’s own set of guiding principles—is uncannily reminiscent of the Mongol model. Genghis Khan did not operate under a codified law recognized by others; his legitimacy rested on his ability to project force and compel obedience. In a similar rhetorical turn, Trump has framed international law as flexible, secondary, or even optional, insisting that his personal moral compass is the ultimate arbiter in decisions about war, peace, and territorial ambition. This is no mere semantic quirk; it signals a return to a politics of power without principle, where formal constraints are dismissed if they conflict with the leader’s objectives.

Critics argue that such unilateralism undermines the post–World War II international order that sought to constrain might-makes-right politics through multilateral institutions and legal norms. They point out that the Venezuelan invasion and capture of a sitting president without Philippine consent or U.N. authorization contravenes the core principles of sovereignty and non-interference. Meanwhile, Trump’s explicit repudiation of international law reinforces the perception among other states that the global system of norms is optional for the powerful, raising fears of instability and escalation.

Viewed through this lens, the ongoing threats against other nations—whether Colombia, Mexico, or European allies like Denmark over Greenland—function less as diplomatic negotiation and more as a replay of steppe logic in modern guise. The Mongol strategy was always to assure that any defiance would trigger overwhelming reprisal, making overarching fear a mechanism of order. Today’s rhetoric of “all options are on the table” and the dismissal of international legal restraints serve a similar psychological function: to convince adversaries and allies alike that resisting U.S. demands carries unacceptable costs.

What distinguishes this contemporary variant from its historical antecedent is not the underlying logic so much as its instruments and consequences. The Mongols razed cities and slaughtered populations; modern states operate under international scrutiny, mass media, and interconnected economies. But the conceptual throughline—power wielded unilaterally, enforced through force and fear rather than shared norms and mutual obligations—is unmistakable. And Trump’s own admission that his morality, rather than international law, guides his decisions places him in a historical company where the boundary between law and will is dissolved, and global power is asserted on the basis of capability and imagination rather than codified restraint.

In this sense, what we are witnessing may be less a series of isolated interventions and more a systemic shift toward what might be termed “neo-steppe hegemony”—a pattern where dominant states treat international boundaries and norms not as limits but as instruments to be shaped in service of strategic advantage, calibrated through fear, economic leverage, and the explicit threat of violence rather than mutual legal frameworks. Whether this approach will yield lasting influence or provoke global backlash remains an open question; what is clear is that drawing analogies to the Mongol model helps illuminate the structural logic behind a foreign policy that increasingly prizes unilateral power over shared order.