Tariq Mahmood Awan

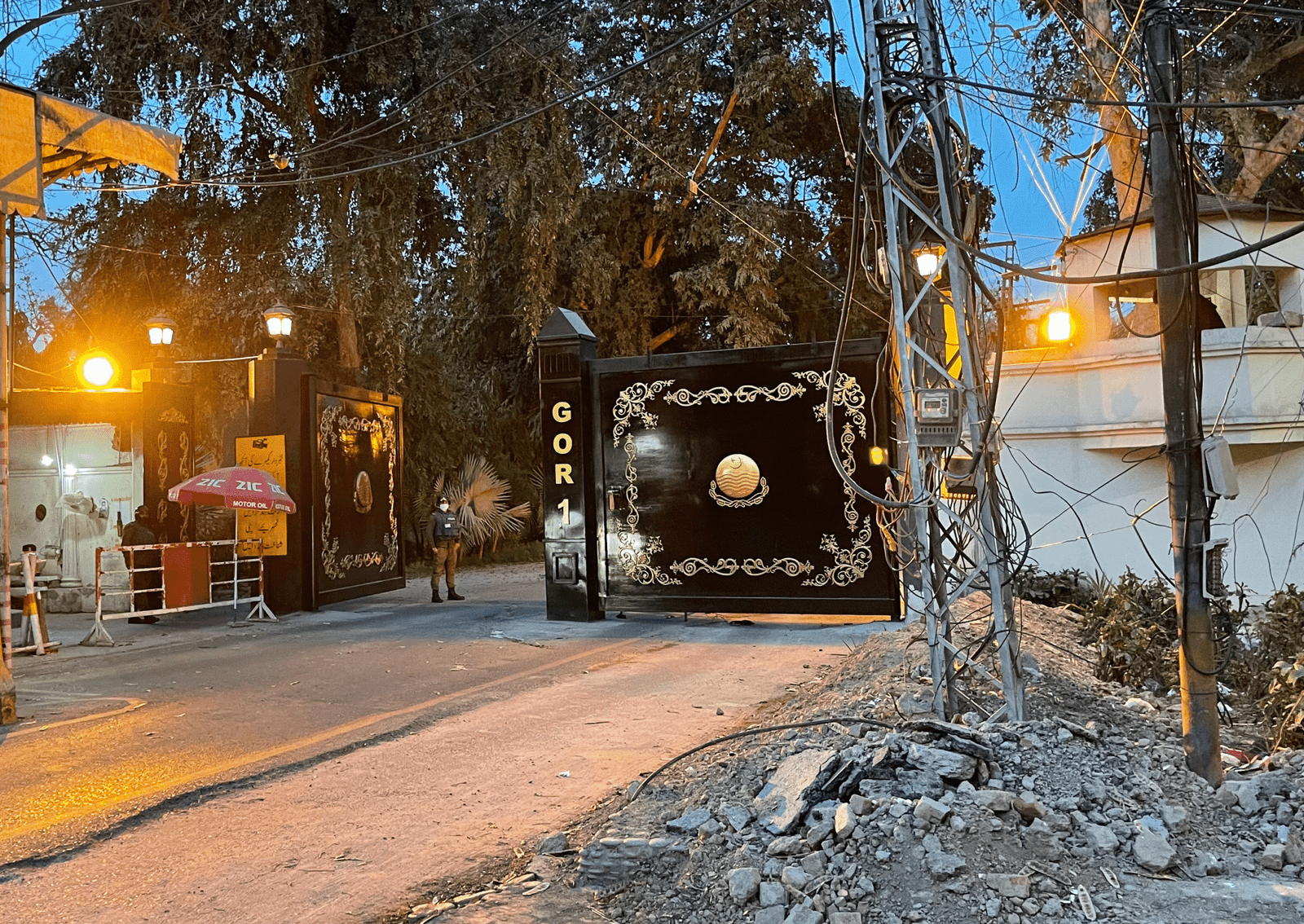

The Government Officers Residences (GORs) of Lahore stand as a glaring contradiction in Pakistan’s administrative order. Designed as elite state-owned colonies for civil servants, these housing schemes have today become the most encroached societies in the city. The irony is bitter: the very officers who sit in enforcement bodies such as the Punjab Enforcement and Regulation Authority (PERA) and oversee demolitions across Lahore are themselves residing in encroached houses, flats, and residences within GORs. This hypocrisy not only questions the moral character of the bureaucracy but also exposes the absence of accountability in the use of public land and resources.

The Supreme Court of Pakistan has repeatedly stressed that civil servants are the custodians of the Constitution and the law. Their professional ethos, by principle, should be rooted in safeguarding the state and public interest. Yet the record shows the opposite. Instead of implementing laws, bureaucrats have often been found to manipulate, bend, and maneuver rules to protect elite interests. They function less as neutral administrators and more as agents of powerful brokers, blurring the line between governance and collusion. It is no exaggeration to state that many civil servants have drifted into the category of white-collar criminals.

The history of Pakistan’s bureaucracy is riddled with constitutional and legal contradictions. Take the case of the most powerful service—the Pakistan Administrative Service (PAS), previously known as the District Management Group (DMG). How can a federal service rest on the provincial posts in a federation? Its very existence rests on the 1954 CSP Cadre Rules, crafted in a colonial context. How can rules designed in 1954 withstand the federal-parliamentary system introduced after the 18th Constitutional Amendment? The persistence of PAS is itself a product of administrative fraud, highlighting how outdated frameworks are kept alive to protect entrenched privileges rather than to serve the federation.

In Punjab, the epicenter of administrative power, the Services and General Administration Department (S&GAD) exemplifies this unchecked bureaucratic dominance. Unlike many provincial agencies that are rooted in legislation, S&GAD was never created through an act of the Punjab Assembly. Instead, it operates under the Rules of Business framed under Article 139 of the Constitution. But Rules of Business are merely instruments of business allocation—they cannot establish a department. This constitutional anomaly has had devastating consequences. A department without a legislative foundation operates purely on executive discretion, allowing civil servants to shape policies, regulations, and allotments according to their whims, free from parliamentary oversight.

https://facebook.com/RepublicPolicy

The dysfunction of S&GAD is visible most clearly in the management of GORs. Allocation, repair, and maintenance of residences have become a cesspool of corruption, nepotismand favoritism. Housing categories are brazenly violated. Houses are handed out as rewards for loyalty to officers rather than on merit or eligibility. Officers serving in S&GAD ,CM Secretariat or who are close to Chief Secretary are allotted houses beyond their categories. A transparent dataset of allotments would expose the systematic abuse of discretion and favoritism that has defined this process for decades.

https://tiktok.com/@republic_policy

Then, the next question is, how the civil servants live in GORs? Encroachments within GORs represent the most visible form of this abuse. Officers routinely alter house structures according to their personal desires, ignoring master plans and approved building maps. Green belts are converted into private lawns, servant quarters are expanded into illegal annexes, and adjoining public spaces are absorbed into private compounds. Even streets and pathways are obstructed by unauthorized constructions. Instead of acting against these violations, S&GAD officers either turn a blind eye or actively support them. The very enforcers of the law become its violators.

https://instagram.com/republicpolicy

Why is S&GAD silent on these encroachments? The answer lies in the culture of impunity and absence of accountability. Neither the provincial government nor the Punjab Assembly subjects S&GAD’s operations to scrutiny. Policies are made through executive orders, occasionally rubber-stamped by cabinets maneuvered by Chief Secretaries. The latest Allotment Policy 2024, approved by an interim cabinet, is one such example. It is not a legal instrument rooted in legislation but an administrative order. It has no constitutional legitimacy, yet it governs the allocation of public residences worth billions. This unchecked exercise of discretion undermines parliamentary sovereignty and deprives citizens of the financial accountability owed to them. This happens, as there is no legislation, which is governing the S&GAD.

https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaYMzpX5Ui2WAdHrSg1G

GORs are not simply housing colonies—they are a mirror of Pakistan’s bureaucratic mindset. Officers tasked with removing encroachments across Lahore have themselves compromised GORs’ master plans. From house allotment to maintenance, from allocation to repair, everything operates at the pleasure of a few senior officers. This hypocrisy highlights the institutional rot where rules are meant for the public but exceptions are carved out for the elite. The result is a loss not only of public trust but also of billions of rupees in state finances.

The way forward is clear. First, S&GAD must be legislated. The Punjab Assembly, as the constitutional legislature, must regulate the creation, scope, and functions of this powerful department. Second, all housing policies must be brought under statutory law and subjected to public accountability. Third, encroachments within GORs must be documented and demolished, without exception, setting an example of accountability from the top. Finally, civil servants must be reminded that their role is not to serve themselves or their patrons but to uphold the Constitution and protect public interest.

Lastly, GORs represent the most encroached housing societies in Lahore not because of weak laws but because of bureaucratic hypocrisy. When those responsible for enforcing the law become its violators, institutions collapse, and corruption thrives. Safeguarding the rule of law, protecting the public exchequer, and restoring public trust requires that the hypocrisy in GORs end. Bureaucracy must be regulated by law, not by its own discretion. Only then can governance in Punjab and Pakistan align with constitutional principles and democratic accountability. As, S&GAD is wiouth law, therefore, PERA, must act here, and demolish all the encroachment, as they are doing in the rest of Punjab. It is also a test case for PERA.