Barrister Ahmad Ghani

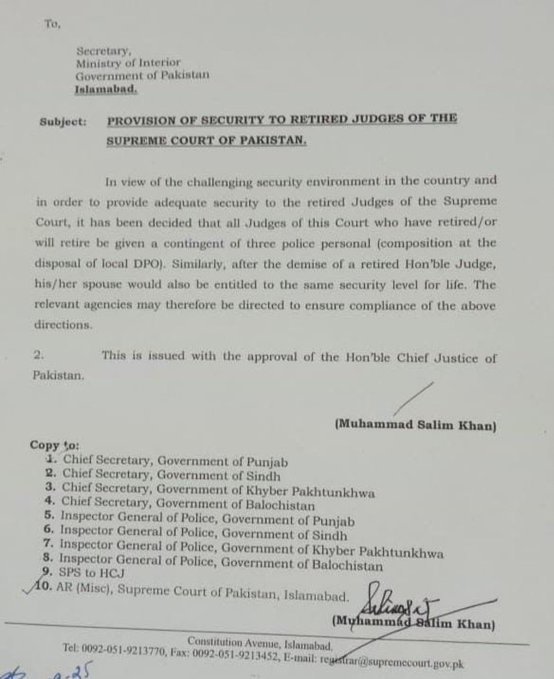

The recent tweets of Khawaja Saad Rafique and Defence Minister Khawaja Asif have once again exposed the long-standing imbalance between Pakistan’s institutions. Both senior politicians have rightly pointed out the glaring disparity in privileges, pensions, and security arrangements extended to retired judges of the superior judiciary. According to Saad Rafique, a retired Supreme Court judge receives not only heavy pensions and allowances but also security in the form of nine police guards if the court’s orders are implemented. In comparison, parliamentarians spend their lives in meagre accommodations, often repairing two small government flats over decades without additional luxuries.

Khawaja Asif, in his retweet, lamented the irony that judges, even after retirement, continue to enjoy a life of power and security. He candidly remarked that politicians survive on limited salaries, media scrutiny, and often negligible security, while judges open “new shops” after retirement, benefitting from state-funded privileges. This is not just a tale of political frustration; it is a reflection of systemic imbalance. The state, as Khawaja Saad Rafique emphasized, can no longer bear the burden of elites’ unlimited desires while ordinary citizens struggle under inflation, unemployment, and insecurity.

However, amid their valid criticism, one fundamental contradiction remains. Both Khawaja Asif and Khawaja Saad Rafique are not mere commentators—they are parliamentarians and former federal ministers. They belong to the very institution that holds constitutional supremacy. The Constitution of Pakistan is unambiguous: Parliament is the supreme legislative body, empowered to regulate the terms, conditions, and privileges of all branches of the state, including the judiciary and the civil bureaucracy. If legislators believe judicial perks are unjust, the responsibility to rectify this lies with them, not with social media complaints.

It is the legislature alone that possesses the authority to pass laws, amend constitutional provisions, and regulate institutional privileges. Articles of the Constitution and parliamentary procedure empower legislators to intervene where executive or judicial overreach is visible. Why, then, does the legislature hesitate? Why do politicians lament in tweets but fail to bring legislative resolutions or bills before the National Assembly and Senate? This question strikes at the very heart of Pakistan’s democratic deficit.

https://facebook.com/RepublicPolicy

The larger issue is that Pakistan’s political class has historically ceded space to unelected institutions—judiciary and military bureaucracy—either out of expedience or fear. Judicial activism has, over decades, eroded parliamentary authority. The bureaucracy, too, has entrenched itself through Rules of Business, summaries, and executive orders. As a result, the legislature, instead of asserting constitutional supremacy, often becomes a bystander. Political leaders, even when in power, avoid confrontation with judges and generals. Instead, they choose rhetorical resistance on public forums, which ultimately changes nothing.

https://tiktok.com/@republic_policy

The irony lies in the fact that every judge’s pension, security, and privilege stems from legislative enactments or judicial interpretations thereof. Parliament has the power to amend or repeal such provisions. For instance, if nine police guards for retired judges are unsustainable, Parliament can legislate a new framework defining security entitlements for all state officials, including judges, generals, and politicians. Parliament can also create oversight committees to ensure that no executive notification grants undue privileges beyond legislative sanction. Yet, legislators rarely exercise this power.

https://instagram.com/republicpolicy

This legislative inaction breeds a dangerous precedent. When politicians appear helpless before judicial decisions, it sends a message that Parliament is weak and irrelevant. Citizens, observing this imbalance, lose faith in democratic processes. Instead of looking to their elected representatives for justice and reforms, people see politics as powerless and turn toward other institutions. This is precisely why Pakistan suffers from recurring cycles of judicial and military dominance—because Parliament refuses to play its constitutional role as the supreme regulator.

https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaYMzpX5Ui2WAdHrSg1G

The responsibility now rests squarely on the shoulders of legislators like Khawaja Saad Rafique and Khawaja Asif. Their words must translate into action. If they believe judicial perks are exploitative, they must initiate parliamentary debate, draft legislative amendments, and mobilize public support for reform. Parliament should establish clear principles of equality, fairness, and austerity in regulating the privileges of all state elites. The judiciary and bureaucracy cannot remain self-regulated cartels; they must be accountable to the people’s representatives. Otherwise, tweets and complaints will be nothing more than political theatre.

The time for mourning is over. The Constitution places Parliament at the apex of governance, and legislators cannot abdicate this responsibility. If judicial perks are unjust, it is not the judiciary that should be blamed alone; it is also the legislature that fails to legislate. The people of Pakistan deserve answers from their representatives: Why do you complain when you hold the power to act? The burden of reform lies not on social media posts but on the floor of Parliament. Unless political leaders rise to this responsibility, the cycle of elite privileges will continue, crushing the common citizen under its weight.