Tariq Mahmood Awan

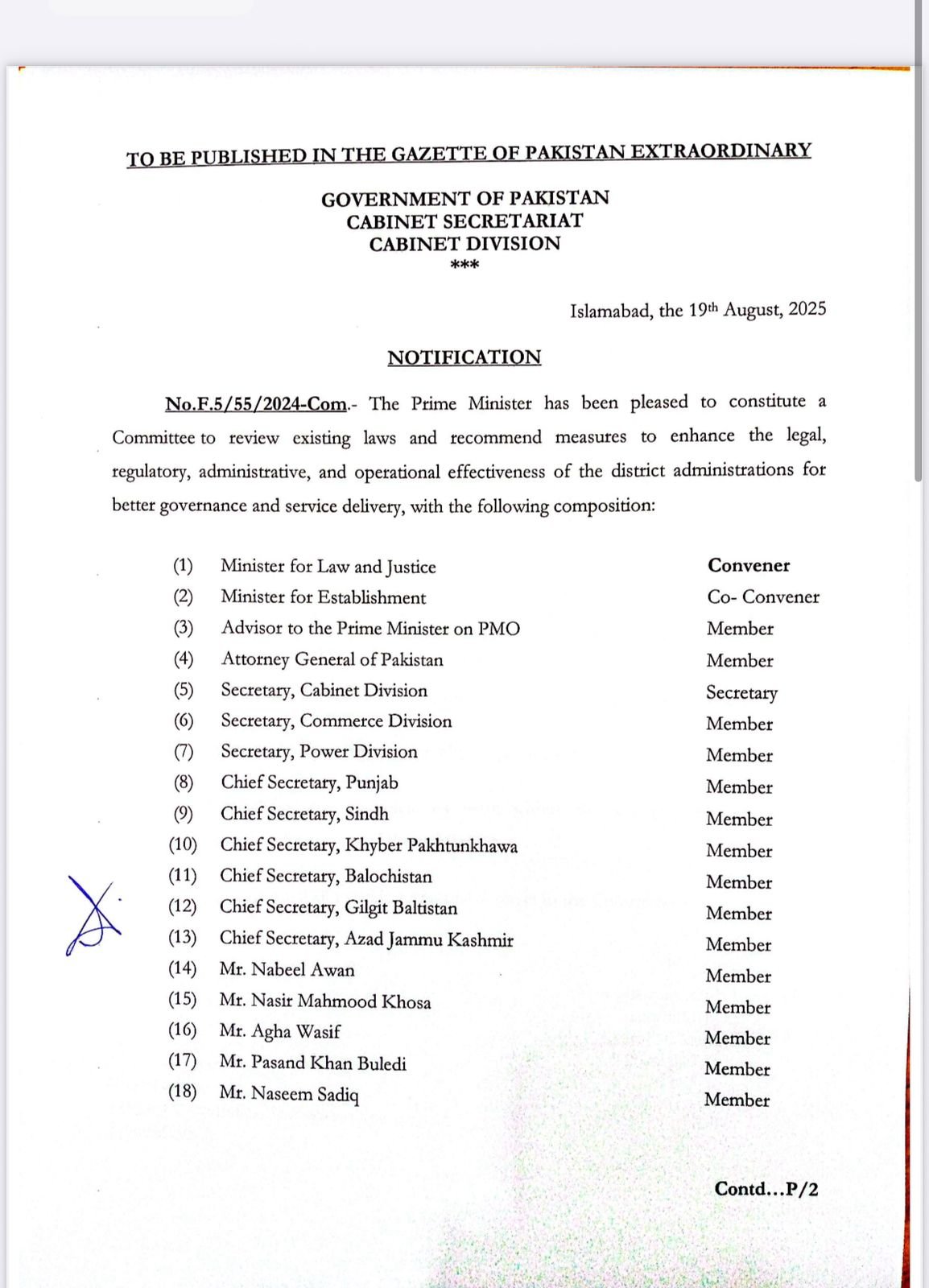

Pakistan’s governance debate has entered a new phase with the federal government’s recent notification establishing a committee on district administration. On the surface, this may appear to be a routine bureaucratic exercise, but a deeper examination reveals its constitutional and political contradictions. District administration is not, and never has been, a federal subject. It falls under the jurisdiction of provincial governments, and through Article 140-A, under the authority of elected local governments. The federal government’s attempt to regulate or redesign district administration not only raises constitutional objections but also undermines the democratic spirit of devolution and federalism. http://republicpolicy.com

Constitutional Context: Article 140-A and Schedule Four

The Constitution of Pakistan clearly delineates the boundaries of administrative authority. Schedule Four explicitly excludes district administration from federal jurisdiction. Article 140-A, inserted through the 18th Amendment, obligates provinces to devolve political, administrative, and financial responsibility to elected local governments. This provision was meant to institutionalize grassroots democracy, ensuring that citizens enjoy representation closer to their daily lives. By stepping into district administration, the federal government undermines this constitutional balance. It not only usurps provincial legislative competence but also sidelines the local government system envisioned by Article 140-A. In essence, the notification is unconstitutional and represents a regression from Pakistan’s hard-won federal consensus. https://www.youtube.com/@TheRepublicPolicy

Bureaucracy Versus Political Executive in Districts

Historically, Pakistan’s district administration has been dominated by bureaucrats—most notably deputy commissioners and commissioners—who inherited their powers from colonial structures. This model views administration as a matter of control rather than service. It thrives on hierarchy, centralization, and bureaucratic insulation from public accountability. Yet, in a democratic federation, district administration cannot be the monopoly of civil servants. The principle of representative government demands that political executives—mayors, nazims, or councillors—be the real decision-makers at the local level. Bureaucrats may remain as professional managers, but only under the authority of elected leaders. To allow otherwise is to perpetuate a colonial mindset that subordinates citizens to unelected officials.

Musharraf’s Local Government Model: Lessons and Legacy

Pakistan has already tested a radically different model under General Pervez Musharraf’s devolution plan (2001). The local government system he introduced replaced deputy commissioners with elected nazims, who became heads of district administration. These nazims coordinated public order, service delivery, and development with line departments, making the district a truly representative unit of governance. Critics often argue that Musharraf’s system was politically motivated to bypass provincial assemblies. While this may hold some truth, its governance outcomes cannot be dismissed. It gave citizens direct access to their district leaders, improved local accountability, and broke the monopoly of bureaucracy. Compared to the stagnant models before and after it, the Musharraf system remains Pakistan’s most genuine experiment with grassroots democracy. The lesson is clear: when authority is devolved to elected representatives, governance improves. When it is re-centralized into bureaucratic hands, citizens suffer neglect, inefficiency, and detachment. https://facebook.com/RepublicPolicy

Do Districts Still Need Deputy Commissioners?

The most pressing question is whether Pakistan still needs deputy commissioners (DCs) as heads of district administration. In modern governance, the answer is increasingly negative. DCs represent a bureaucratic model designed for colonial control, not democratic service. They combine executive, judicial, and developmental powers in one office, creating both inefficiency and a lack of accountability. Globally, local governments operate without DCs. Instead, elected mayors or councils provide political & executive leadership, while professional managers and departmental officers deliver technical expertise. In countries like India, the UK, and Bangladesh, bureaucrats serve as facilitators, not masters, of local governance. Pakistan’s insistence on maintaining DCs as all-powerful district bosses is an anachronism that undermines the very idea of devolution. Districts do not need DCs—they need empowered mayors and councils, supported by municipal professionals. Federal and provincial governments can maintain coordination offices in districts, but administrative control must rest with local governments. Anything less is undemocratic. https://www.tiktok.com/@republic_policy

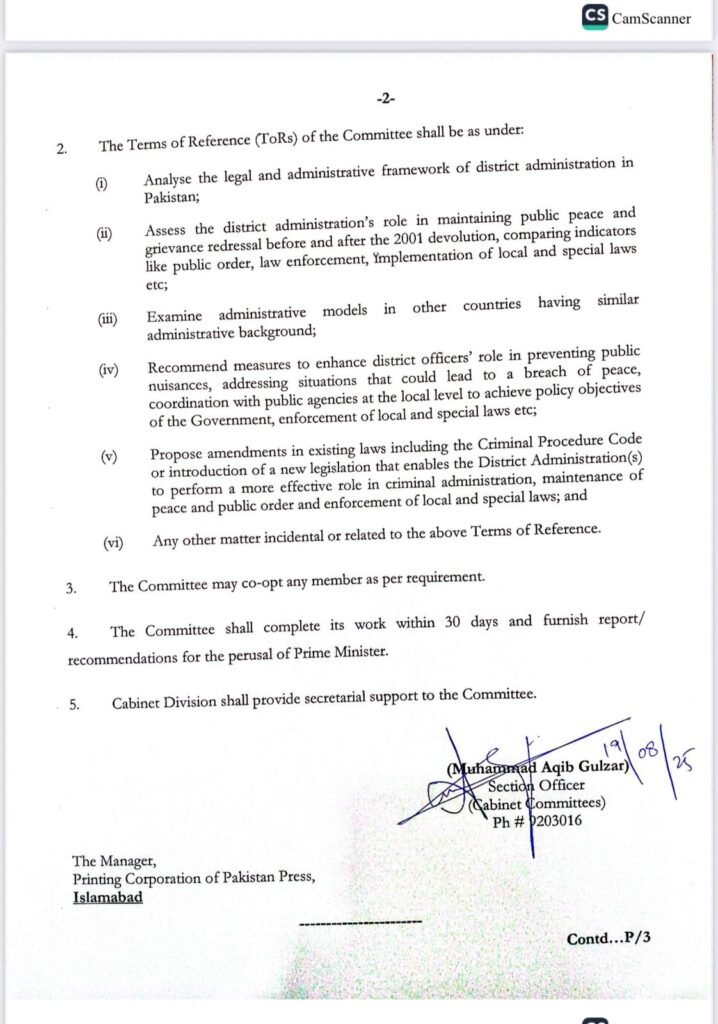

The Federal Committee: Why It Is Unconstitutional

The Cabinet Division’s notification mandating a committee to examine district administration is unconstitutional on multiple counts. Violation of Federalism: District administration is not a federal subject under Schedule Four. The federation cannot legislate or regulate this domain. Encroachment on Provinces: Only provincial governments can design administrative structures for districts. The federal move bypasses provincial autonomy, violating the 18th Amendment spirit. Undermining Local Governments: Article 140-A empowers local governments, not federal committees. By involving itself, the federal government sidelines constitutionally guaranteed local institutions. Colonial Legacy Resurfacing: Instead of advancing devolution, the federal government seeks to re-empower bureaucracy, reversing decades of progress toward democratic local governance. For these reasons, the notification is unconstitutional and risks being struck down if challenged in court.

https://instagram.com/republicpolicy

Comparative Perspective: Global Models of District Governance.

Looking beyond Pakistan, most democratic systems rely on local governments as the cornerstone of district administration. India: After the Constitutional Amendments, district and municipal bodies became central to governance. District collectors exist, but their role is administrative coordination, not political control. United Kingdom: Local councils and mayors govern districts, while civil servants implement policy. District administration is inherently a local function. Turkey: Elected mayors lead municipalities, even in major cities. Governors coordinate central government policy but cannot replace local authority. These models confirm that political leadership at the district level is essential for accountability and service delivery. Bureaucrats serve as advisers and coordinators, not rulers. Pakistan must learn from these examples rather than cling to outdated colonial frameworks. https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaYMzpX5Ui2WAdHrSg1G

Recommendations for Reform

The first and most urgent reform is the abolition of the deputy commissioner’s monopoly over district administration. The colonial-era office of the DC represents an outdated and centralized model of governance where unelected bureaucrats monopolize executive, quasi-judicial, and developmental powers. Modern governance demands elected mayors and councils to act as the true heads of district administration, with bureaucrats serving only as professional managers under their political leadership. Replacing DCs with elected local representatives would restore accountability to the people and democratize the functioning of the state at its most critical tier.

Equally important is the strengthening of Article 140-A. While this constitutional provision mandates political, administrative, and financial devolution to local governments, its spirit has been undermined by weak provincial laws and frequent political manipulation. Provinces must legislate with clarity, ensuring that local governments enjoy permanent continuity, fiscal autonomy, and genuine administrative authority. Without a robust implementation framework, Article 140-A risks remaining symbolic rather than transformative.

Provincial and federal governments, however, should not be excluded entirely from districts. Coordination offices must be allowed for monitoring, implementing national programs, and ensuring policy consistency. Yet these offices should only coordinate, not control. Local governance must remain in the hands of elected representatives, with provincial and federal offices limited to advisory and oversight roles. This balance would preserve both provincial autonomy and local democracy.

To further professionalize governance, Pakistan should adopt municipal management models that separate political leadership from technical expertise. Elected mayors and councils would provide vision and accountability, while professional district or city managers would ensure efficiency, planning, and specialized service delivery. This dual structure would protect democracy from being undermined while also addressing the complexities of modern urban and rural administration.

Civil society and political actors must also be prepared to legally challenge unconstitutional federal interventions. The recent notification forming a federal committee on district administration blatantly violates Schedule Four and Article 140-A. Contesting such moves in courts would establish important precedents to safeguard devolution and prevent future encroachments by the centre. Judicial enforcement of constitutional guarantees is essential to entrenching grassroots democracy.

Finally, public accountability must become the anchor of local government reform. Citizens must be encouraged to demand stronger, empowered local bodies as a direct path to better service delivery, transparency, and responsiveness. Without grassroots pressure, political elites will continue to centralize power and weaken local democracy. Civic awareness, advocacy, and participation are crucial in making local governance both viable and sustainable.

In conclusion, Pakistan’s governance failures stem largely from centralization and bureaucratic monopoly. The attempt to re-engineer district administration through a federal committee is unconstitutional, violating Schedule Four and Article 140-A, and undermining the spirit of devolution. True district administration belongs to local governments. Bureaucrats may serve as facilitators, and coordination offices of provinces and the federation may exist, but authority must rest with elected representatives. The Musharraf-era devolution, despite its flaws, proved that grassroots governance thrives when power is genuinely devolved. The way forward is clear: abolish the deputy commissioner model, empower local governments, and strengthen federalism through authentic devolution. Anything less will leave Pakistan trapped in inefficiency, illegality, and public alienation, with democracy weakened at its foundation. This notification is therefore not only unconstitutional—it is a betrayal of federalism itself.

The writer is a civil servant.