Mubashar Nadeem, Hafeez Ali Khan, Tahir Maqsood Chheena

Introduction

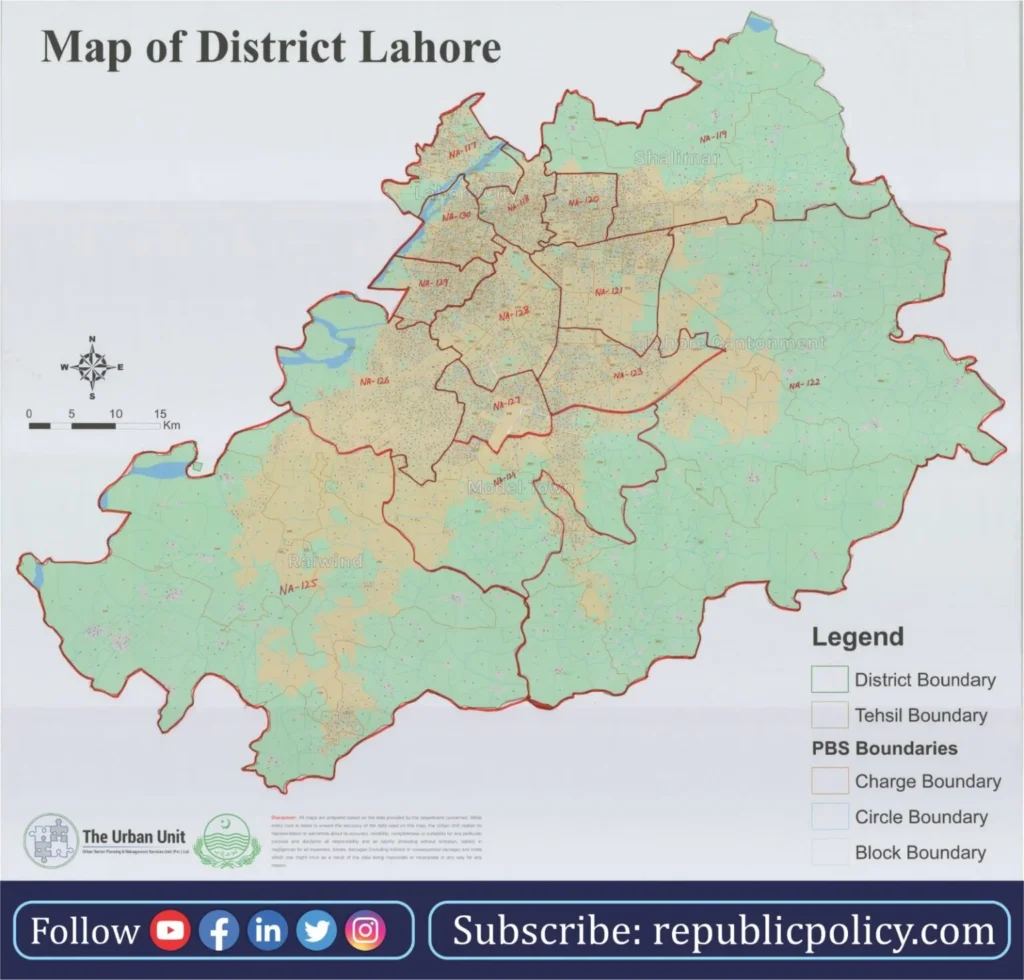

Lahore, the political and cultural heart of Pakistan, holds a pivotal role in shaping national and provincial politics. Represented by 14 constituencies in the National Assembly and 30 in the Punjab Provincial Assembly, the city’s electoral landscape reflects a complex interplay of urban priorities, party loyalties, and shifting voter sentiments. With a diverse electorate spread across historic neighborhoods, commercial hubs, and expanding suburban areas, Lahore serves as both a stronghold for traditional political forces and a testing ground for emerging movements. Its electoral trends not only influence the balance of power in Punjab but also carry significant weight in determining the national political direction—making it an indispensable focal point for any political survey or electoral analysis.

Map of Lahore:

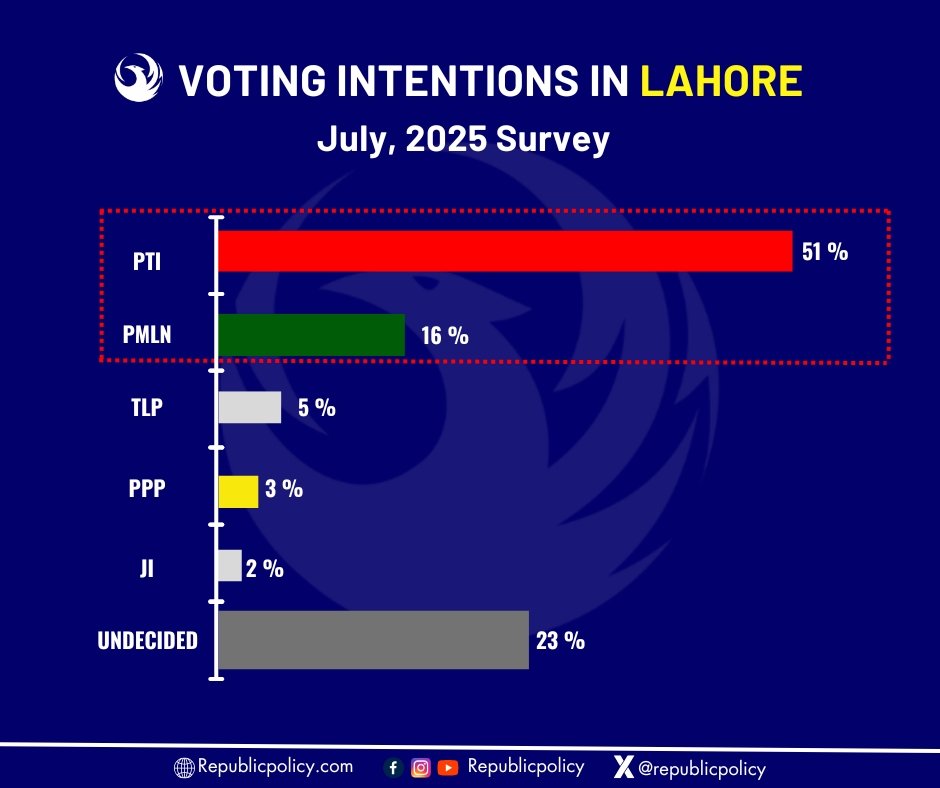

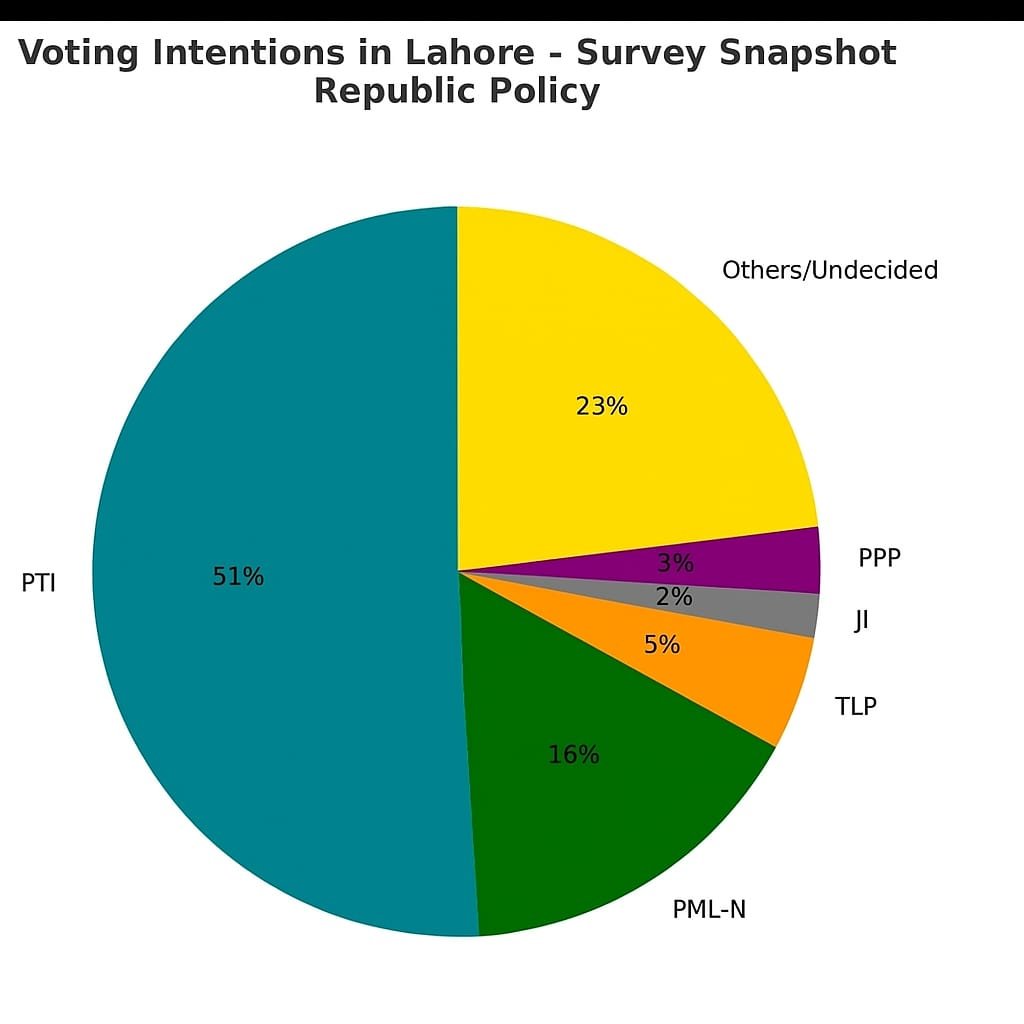

A new survey conducted in July 2025 by Republic Policy Think Tank gauged voter intentions across Lahore district, revealing a dramatic lead for the opposition Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) over the ruling Pakistan Muslim League–Nawaz (PML-N). The poll sampled 3,000 respondents from all 274 union councils of Lahore, using standard sampling techniques to ensure representation of genders, professions, age groups, and localities. Respondents were asked a straightforward question: “If elections are held in July 2025, whom will you vote for?” The results show PTI commanding 51% of intended votes, a majority of the electorate, while PML-N trails at 16%. Other parties, including the religious Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) at 5%, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) at 3%, and Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) at 2%, together make up a small fraction of preferences. Notably, 23% of those surveyed remain undecided or inclined toward minor candidates. This report provides a comprehensive analysis of these findings – explaining the survey methodology, the demographic makeup of respondents, and the political and cultural reasons behind the support for each party – particularly the dominant PTI and the lagging PML-N. It also discusses the high proportion of undecided voters and what their uncertainty could mean, drawing on comparative insights from previous Republic Policy surveys and articles to place the 2025 Lahore poll in context. The goal is an evidence-based, balanced assessment in the public interest, presented in an accessible format for both local and international readers.

Survey Methodology and Sample Demographics

The survey methodology was designed to ensure that the sample accurately reflects the diverse population of Lahore. Following Republic Policy’s established approach, the basic sampling unit was the union council (UC) – the smallest administrative subdivision in the city[1]. Lahore is divided into 274 union councils, and the survey included respondents from every single UC, making it truly district-wide in coverage. Rather than cluster all interviews in a few areas, the poll adopted a stratified sampling strategy across localities: each UC contributed a set of respondents roughly proportional to its population size, ensuring that densely populated urban neighborhoods and smaller peri-urban communities were represented according to their weight. On average, about 10–12 voters were surveyed per union council (totaling 3,000 citywide), with slight adjustments so larger UCs had more interviews and smaller ones fewer. This approach mirrors a previous Republic Policy constituency-wise survey of Lahore that sampled at least 25 voters per UC[1], albeit the current exercise uses a somewhat smaller sample. By covering all parts of the district, the survey captures Lahore’s geographical diversity – from the inner-city precincts to suburban housing colonies – which is crucial in a city known for varied voting patterns in different localities.

In addition to geographic stratification, the sample was balanced on key demographic indicators. Roughly half of respondents were women, reflecting efforts to hear the voices of female voters who are sometimes underrepresented in Pakistani surveys. All age groups eligible to vote were included: young adults (18–29), middle-aged voters, and seniors. In fact, Lahore’s electorate is very youthful – about two-thirds of voters are young, a factor the survey reflects in its sample composition[2]. Educational and economic backgrounds were also considered; respondents ranged from less-educated daily wage earners to highly educated professionals and entrepreneurs, with income levels spanning working class to upper-middle class. The survey team ensured outreach to a variety of professions – including students, private sector employees, government servants, traders, laborers, and others – to mirror the occupational profile of the city. By capturing this broad socio-economic spectrum, the poll results carry credibility across different segments of society.

Standard polling procedures were followed to minimize bias. Respondents were selected randomly within each union council, often through door-to-door visits or at public gathering points, using face-to-face interviews with a structured questionnaire. This method provides rich and authentic data, as it allows engagement with voters directly in their communities[3]. In some cases, where direct access was difficult, telephone interviews were used as a supplement – a faster approach but one that can risk lower response rates[4]. The questionnaire itself was kept very simple: essentially a single voting intention question (“Which political party will you vote for if elections are held today?”), identical to that used in prior Republic Policy surveys[5]. Keeping the questionnaire short helped improve response accuracy and rate, as respondents only had to consider one main question. However, the survey was more than just a quick poll – researchers also gathered qualitative feedback and observations. In line with Republic Policy’s methodology from earlier polls, the team solicited five key feedback points in discussions with respondents and local community observers: who they see as the most popular leader, the most popular party, the favorite local candidate, their first vote preference, and their second choice if any[6]. These additional insights help contextualize the single-choice voting intention by illuminating broader perceptions (for example, a respondent might intend to vote PTI but still acknowledge Nawaz Sharif’s past projects, or vice versa). All field data collection took place within the month of July 2025, ensuring a fresh snapshot of opinion. With a sample of 3,000, the margin of error is around ±2 percentage points at the 95% confidence level (assuming a random sample) – meaning the findings are reasonably accurate for the population of Lahore, though normal caveats about sampling and response bias apply. Republic Policy emphasizes that careful survey design is essential to produce reliable insights for the political process[7], and indeed every effort was made to uphold transparency and rigor in this poll’s execution.

Lahore’s Political Landscape and Context

Lahore is not just another city in Pakistan – it is the political heart of Punjab, and by extension crucial to national politics. The city’s significance comes from its size, economic clout, and historical role as a power base for major political leaders. Two of Pakistan’s most prominent politicians hail from Lahore, embodying a long-standing rivalry on the national stage[8]. Nawaz Sharif, three-time former Prime Minister and patriarch of PML-N, built his career and loyal following in Lahore over decades – his party has traditionally dominated the city’s politics through a mix of infrastructural development (earning Lahore the nickname “Nawaz’s city” in the 1990s) and patronage networks. Imran Khan, the cricketer-turned-politician and chairman of PTI, is also a Lahori by birth; although his political rise was initially outside the traditional Lahore scene, by the 2010s he marshaled massive urban middle-class support here. The clash between PML-N and PTI in Lahore has thus been cast as a battle of titans: a contest between the old guard represented by the Sharifs and the new anti-establishment wave led by Imran Khan. Heading into 2025, this rivalry remains the defining feature of Lahore’s political landscape – with the crucial difference that PTI now appears ascendant in public favor while PML-N struggles to regain lost ground.

Political Trends in Lahore–

Several recent developments set the backdrop for the July 2025 survey. Pakistan’s last general election (originally scheduled for 2023) was eventually held amid controversy – PML-N and its allies took power, whereas PTI alleged widespread manipulation. Indeed, it is pertinent to note that the official 2024 election results may not have painted the true picture of the electorate’s will, given disputes over result tabulations (the infamous Form-45/47 issues)[9]. Lahore, which had been a PML-N stronghold in previous elections, saw a highly charged atmosphere. In the 2018 general election, for example, PML-N won 10 out of 14 National Assembly seats in Lahore (and later captured an eleventh in a by-election), leaving PTI with only 3 or 4 seats[10]. That reflected PML-N’s entrenched urban vote bank at the time. However, by late 2023, the tide was already turning. The Republic Policy survey in October 2023 (ahead of the then-anticipated elections) found PTI surging in Lahore: it indicated PTI was on track to lead in 7 of Lahore’s NA constituencies, with PML-N ahead in only 2, and the remaining 5 seats too close to call (competitive within a 10% margin)[11]. The baseline assumption of that survey was a fair contest – i.e. both PTI and PML-N candidates appearing on the ballot and no major rigging – under which the findings were expected to mirror election outcomes[12]. This was a striking change from past elections and signaled a wave in PTI’s favor. By early 2024, events took a dramatic turn: Imran Khan was jailed and many PTI leaders faced a crackdown, while Nawaz Sharif returned from exile to resume PML-N’s leadership. PML-N took over the federal government as part of a coalition. Yet, instead of consolidating public support, the ruling alliance became associated with a severe economic downturn – high inflation, unemployment, and governance woes – which eroded its popularity[13][14]. The incumbency factor flipped: where PTI had once borne voter dissatisfaction for its governance shortcomings, now PML-N was the target of public frustration over rising prices and perceived ineffectiveness[14]. In Lahore, a city acutely sensitive to prices of food, fuel and housing, this economic discontent has been politically devastating for PML-N’s image.

At the same time, PTI has managed to keep its narrative alive among the masses. Despite the absence of Imran Khan from the public arena (owing to legal troubles), his message of fighting the “status quo” and promises of justice and accountability (the “Naya Pakistan” reform agenda) continue to resonate. Social media and grassroots community networks in Lahore have kept the PTI slogan afloat, even when mainstream media coverage turned lukewarm. Initially, after being ousted in 2022, PTI struggled to perform as an opposition and faced media blackouts. But the situation evolved; by late 2023 and into 2024, the party’s base in urban Punjab had galvanized around what they saw as an unjust crackdown against their leader. Sympathy for Imran Khan and anger at the old elites gave PTI’s support a passionate, almost movement-like quality. Lahore’s culturally vibrant and politically aware populace, especially the youth, have been at the forefront of protests and online campaigns backing PTI. Observers noted that even when PTI’s formal campaign machinery was hampered – for instance, some PTI candidates in Punjab by-elections faced harassment and arrests in early 2024 – the underlying public sympathy for the party remained strong[15]. As the 2025 survey reveals, that sympathy has translated into solidified voter intentions favoring PTI.

Another critical aspect of Lahore’s political context is the generational shift. The majority of Lahore’s voters today are young (under 35), many voting for the first or second time. This generation is less bound by traditional party loyalties and more influenced by issues like corruption, jobs, social justice, and personal freedoms. PTI has a clear edge with these young voters – a point underscored in Republic Policy’s earlier analysis that two-thirds of young voters are inclined toward PTI, and PML-N’s foremost challenge is to win over this youth demographic[2]. Conversely, PML-N’s core support lies among older voters who recall the economic growth and stability of the 1990s or early 2010s under Nawaz Sharif, as well as among merchant and trader classes who have longstanding ties with the Sharif family’s network. Lahore’s famed kinship groups (biradaris) and local patronage systems, which PML-N traditionally excels at mobilizing, are still a factor but to a lesser extent in this metropolitan setting. The caste and biradari influence is weaker in Lahore compared to rural Punjab – it only marginally affects a few pockets, mostly in the northern and eastern parts of the city[16]. This weakening of clan-based voting means performance and ideology-based appeals carry more weight in urban Lahore. In summary, as Lahore heads toward the next election, the stage is set with PTI riding a wave of popular demand for change, and PML-N trying to rekindle its old glory by emphasizing experience and development. The survey results below reflect this dynamic in stark terms.

Survey Results: PTI’s Big Lead in Lahore

Figure 1: Voting intentions in Lahore (July 2025) – PTI holds a majority share of the respondent preferences at 51%, far ahead of any other party. PML-N is a distant second at 16%, while smaller parties like TLP (5%), PPP (3%), and JI (2%) make up only a minor portion of the pie. A significant segment, 23%, represents voters who are undecided or prefer other candidates, highlighting a substantial swing pool that could influence the final outcome.

The data unequivocally points to a dominant position for PTI in Lahore’s voter landscape as of mid-2025. With 51% of those surveyed choosing PTI, Imran Khan’s party enjoys an outright majority of support – more than the combined total of all other parties. This is an extraordinary figure, considering that in the last competitive election PML-N had led in Lahore; it underscores a reversal of fortunes fueled by the factors discussed earlier. At 16%, PML-N’s support in this poll is less than one-third of PTI’s – a gap that would translate into a landslide defeat for PML-N in Lahore if replicated at the ballot box. Such a wide margin between the top two parties is rarely seen in Pakistani politics, especially in an urban center historically known as a PML-N fortress. For context, in past elections PML-N could usually count on 40%+ of Lahore’s vote; seeing it languish in the mid-teens reflects both the collapse of its vote bank and the consolidation of anti-incumbent sentiment behind PTI.

The minor parties collectively account for around 10% of intended votes in the survey. The TLP (Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan) registers at 5%, making it the third-largest choice among Lahori voters in this poll. TLP’s niche has been as a hardline religious movement appealing to sentiments around blasphemy and the honor of the Prophets; it demonstrated surprising electoral strength in 2018 in Lahore by securing a notable number of protest votes. A 5% share today suggests TLP retains a presence, likely concentrated in specific neighborhoods, particularly among lower-income religiously conservative communities. However, TLP remains far behind the mainstream parties here. The PPP (Pakistan Peoples Party), once a major party in Punjab decades ago, shows a mere 3% support in this survey. PPP’s negligible standing in Lahore is not surprising – the Bhutto-led party has not won a significant seat in Lahore in a long time, and is generally perceived as a Sindh-based or rural Sindh party in recent times. The 3% presumably comes from pockets of old PPP loyalists, some minority communities (PPP has tried to court Christian voters in Punjab as noted in a recent by-election campaign[17]), and individuals nostalgic for the Bhutto legacy. JI (Jamaat-e-Islami), an Islamist party with a long history in urban Punjab, polls at 2%. JI’s support likely comes from its dedicated ideological followers – the party has an active presence in Lahore through its charitable networks and educational wings, and its headquarters (Mansoora) is in Lahore. Still, 2% indicates JI’s influence is limited and many religiously-inclined voters have shifted to either TLP or PTI. All other parties and independent candidates are grouped under “Others”. This category, together with undecided voters (the survey combined them in the 23% slice), covers any new entrants and minor players. For instance, the newly formed Istehkam-e-Pakistan Party (IPP) of Jahangir Tareen – a PTI breakaway faction launched in 2023 – would fall under “Others” here; the fact that IPP was not broken out separately implies its support is minimal in Lahore so far (likely well under 2–3%). In sum, aside from PTI’s commanding lead and PML-N’s residual base, no other single party currently registers above the low single digits in Lahore’s urban electorate.

To visualize the stark contrast in support levels, the survey results are also presented as a bar chart below, highlighting how substantially PTI towers over its rivals in voter intentions:

Figure 2: Bar chart of voter intention percentages from the Lahore survey. PTI’s support (51%) is more than triple that of PML-N (16%), vividly illustrating the gap. The minor parties (TLP, PPP, JI) barely register by comparison. The “Others/Undecided” group forms the second-largest bar at 23%, indicating a significant portion of the electorate that is up for grabs or not aligned with the major parties.

The bar graph underscores the key takeaway: PTI is the clear frontrunner in Lahore as of this survey, suggesting that if an election were held today, PTI could sweep most of Lahore’s constituencies with ease. PML-N’s bar, less than one-third the height of PTI’s, confirms that the ruling party is facing a potential rout in a city that used to be its citadel. The minor party bars are almost negligible in height – a visual reminder that this is essentially a two-party contest in terms of viable power, with PTI well ahead and PML-N fighting to remain relevant. The “Others/Undecided” bar is notably high, nearly one-quarter of respondents, which we will analyze in detail later. This large undecided segment means that while PTI leads now, the battle is not entirely over – how those currently uncommitted voters break in a future campaign could still influence the final vote tallies.

Before delving into the undecided voters, it is useful to explore why the respondents say they intend to vote the way they do. What political and cultural factors are driving over half of Lahore’s voters into the PTI camp, and what explains PML-N’s steep decline to 16%? The following sections analyze the support bases of the major parties, drawing on both the survey feedback and broader socio-political observations.

Why PTI Is Leading: Factors Behind the 51% Support

The Analysis is only restricted to Electoral popularity not Protest popularity.

PTI’s remarkable 51% share in this survey is the product of multiple factors coalescing to create a wave of support. At its core, PTI’s appeal in Lahore is driven by the promise of change, Ik resistence, and justice that resonates strongly with the urban population, especially the youth. Imran Khan’s narrative of fighting corruption and building a “Naya Pakistan” (New Pakistan) has struck a chord with voters tired of traditional politicians. Younger voters in particular identify with PTI’s outsider image and its calls for accountability of the old ruling families. As noted, around two-thirds of young voters lean towards PTI, a generational swing that gives PTI a huge advantage in Lahore[2]. These digital-native millennials and Gen-Z voters consume independent news on social media, participate in political debates online, and often view Imran Khan as a symbol of national pride and hope for a better future. Republic Policy’s on-ground observations in 2023 found that at colleges and universities in Lahore, an overwhelming majority of students supported PTI regardless of gender[18]. This trend appears to hold in 2025 – the youth vote bank remains firmly in PTI’s column.

Beyond the youth, PTI has also made inroads across various socio-economic groups in Lahore. The survey and accompanying interviews suggest that educated middle-class professionals – including private sector employees, doctors, engineers, academics, and government officers – largely favor PTI. Many in this segment see PTI as the party most likely to reform governance and improve rule of law, aligning with their aspirations for meritocracy and transparency. Republic Policy’s previous research noted that professionals, public servants, and other white-collar workers in Lahore were mostly with PTI[19]. This can be attributed to PTI’s stance on institutional reforms and anti-corruption, which appeals to those frustrated with bureaucratic inefficiency and nepotism. On the other hand, business owners and traders have traditionally been a PML-N constituency due to the party’s pro-business image and patronage networks in marketplaces. However, in this survey we see evidence that even many traders have drifted toward PTI, largely out of disillusionment with the economic crisis under the PML-N-led government[20]. Soaring inflation and currency depreciation during 2024–2025 hit shopkeepers and small businessmen hard, diminishing the goodwill PML-N enjoyed among them. PTI, despite not being in power, has capitalized on this by promising better economic management and highlighting the incumbent government’s failures.

Culturally, PTI’s rise in Lahore also reflects a shift in the political culture of the city from patronage to performance-based expectations. In the past, parties like PML-N nurtured loyalty by delivering visible projects (roads, flyovers, urban services) and through local patron-client relationships (e.g., helping supporters with police cases, bureaucratic paperwork, etc.). While those networks have not vanished, their influence is waning among a more independent-minded electorate. Lahore’s voters today ask tough questions about policy outcomes – jobs, inflation, governance quality – and PTI’s message speaks to these issues. Imran Khan’s rallies in Lahore (prior to his detention) drew massive crowds not just because of personal charisma but because people felt he gave voice to their anger over systemic injustices and elite impunity. PTI has also invoked Islamic moral terminology (talk of justice, an Islamic welfare state, etc.) in a way that appeals broadly without veering into extremism, thus drawing even moderately religious voters who might otherwise consider a party like TLP. This broad-based ideological appeal has given PTI a “big tent” in Lahore, uniting disparate groups under the single banner of change.

Another factor behind PTI’s strength is the organizational and mobilization capability it has built up in urban Punjab. PTI’s cadre in Lahore includes energetic volunteers and local leaders (often from the educated middle class) who engage in door-to-door outreach and effective use of social media. Even though PTI lacked the entrenched local government networks that PML-N enjoyed, over the last few years it cultivated neighborhood committees and donor groups that expanded its grassroots presence. The party’s sophisticated social media operation – far stronger than PML-N’s until recently – has kept supporters informed and galvanized. (PML-N only lately has tried to rejuvenate its social media to counter PTI’s online dominance, a daunting task as one Republic Policy analysis pointed out[21][22].) Moreover, PTI benefits from a loyalty factor: its supporters are highly enthusiastic and likely to turn out to vote come rain or shine. This was evident in previous elections and is likely to be crucial in future ones; analysts note that higher voter turnout tends to favor PTI, given its energized base, whereas a low turnout favors PML-N’s more traditional base[23]. The survey’s implication is that much of PTI’s 51% support is solid – these are voters unlikely to change their mind easily. In fact, Republic Policy’s constituency survey analysis observed that PTI’s popular support in Lahore was so robust that the party could win constituencies “even if they place mediocre candidates and put in [a] mediocre election campaign,” so long as Imran Khan’s emblem (bat) is on the ballot[24]. This underscores how the PTI vote in Lahore is driven by party identification and Imran’s appeal, rather than the personal appeal of individual candidates.

Imran Khan is the fundamental factor for the popularity of PTI:

It is worth noting that PTI’s time in federal power (2018-2022) was not without controversy or policy missteps, and some Lahori voters do remember issues like inflation during that era or governance challenges. However, the context has shifted such that voters now compare PTI’s tenure with the incumbent PML-N’s performance, and many deem PTI the lesser of two evils or even a positive alternative. The “regime change” in April 2022 (when Imran Khan’s government was removed via a no-confidence motion) and the subsequent economic difficulties under the PML-N/PDM government have, in the eyes of PTI supporters, vindicated Imran’s narrative that he was disrupted by corrupt forces just as he was trying to set things right. Cultural factors like a growing disdain for dynastic politics also play in PTI’s favor – PTI positions itself as a movement for ordinary Pakistanis, contrasting with PML-N which is led by the Sharif family and PPP led by the Bhutto-Zardari family. In educated circles of Lahore, such anti-dynasty sentiment is strong; people often quip that “PTI gave us hope that politics can be about issues, not family name.” Whether PTI always lived up to that is debatable, but the perception persists that PTI is a cleaner, more modern political force relative to the older parties.

In summary, PTI’s 51% support in Lahore is bolstered by a convergence of youth support, cross-class appeal, a resonant message of change, and public discontent with the incumbent regime. Lahore’s cultural leanings towards progressiveness and civic nationalism align with PTI’s platform. The party’s ability to embody both an anti-establishment protest and a promise of better governance has given it a decisive edge. As subsequent sections will explore, PML-N faces the daunting task of countering these factors to rebuild its standing.

Furthermore, in 2025, it is the resistence of Imran Khan and his popular appeal against status-quo which is inspiring his voters. As, the state of Pakistan faces serious human rights crisis and institutional fall, the people, are with the tide of populism. The human rights, justice, rule of law and liberties are more important for the voters than projects, development and projections.

PML-N’s Support Base and Challenges

PML-N’s mere 16% support in this Lahore survey rings alarm bells for a party that once prided itself on being “Lahore ka sher” (the lion of Lahore). This low figure underscores how far PML-N’s stock has fallen in the city, and it illuminates the challenges the party faces both politically and culturally. PML-N’s remaining support in Lahore is largely rooted in its traditional base – older generations, long-time loyalists, and certain business and community networks – but even within these groups their hold has loosened. Then, there is a cultural change happening in Pakistan, and PMLN, PPP and Religous political parties are unable to dissect it and transform accordingly.

For details:

Pakistan’s Politics Faces Cultural Wave — Are PMLN, PPP & Religous Parties Ready?

One key element of PML-N’s base is the older voter demographic. Many senior citizens and middle-aged Lahoris have memories of the relative prosperity or big development projects of previous Nawaz Sharif administrations – from motorway projects to Lahore’s flyovers, metros, and improvements in power supply. These voters credit PML-N with urban development and see it as an experienced hand at governance. Accordingly, they have been more forgiving of the party’s flaws, sticking with the “known devil” rather than the “unknown”. In the survey, respondents from the older age brackets showed more inclination toward PML-N compared to youth (though still not a majority among older voters, just a plurality). This reflects a generational loyalty gap – PML-N is essentially polling best with those who have voted for it in multiple past elections, while it has failed to inspire a new generation. Republic Policy’s analysis highlights that PML-N’s foremost challenge is to influence young voters to join their ranks[25], a challenge they have yet to meet. The party’s messaging and platform have not significantly adapted to youth interests – it often leans on past laurels rather than future vision, which doesn’t excite younger voters.

Another component of PML-N’s support are the merchant and trader classes of Lahore. The city’s many wholesale markets, trader associations, and bazaar communities historically aligned with PML-N due to the party’s pro-business reputation and personal relationships cultivated by leaders like Shahbaz Sharif (former Chief Minister Punjab) with traders. In this survey and other recent observations, PML-N still “has a strong presence among traders”, but that presence is “comparatively less due to inflation caused by the PDM government.”[19] Inflation has been a double-edged sword for PML-N: while traders might trust PML-N over PTI in terms of economic know-how, the immediate experience of high costs and reduced consumer purchasing power under PML-N’s watch has alienated many. Business owners who struggled to keep their shops open during fuel price hikes and import restrictions have become skeptical of PML-N’s governance. Some in the trading community also resent the heavy taxation measures the government took to revive the IMF program, feeling that PML-N is no longer the business-friendly party it once was. Thus, PML-N’s grip on this segment has weakened, contributing to the low overall percentage.

Culturally, PML-N’s politics is rooted in patronage networks and local influentials – something that is both a strength and a weakness. In Lahore, the party has long relied on local MPAs, union council chairmen, and biradari elders to mobilize voters, especially in older neighborhoods. These intermediaries (often referred to as “electables” or local baradari leaders) can bring in votes through personal influence and by addressing community-level issues. PML-N is indeed banking on such structures to manage constituencies, as one analysis notes: the party will try to leverage “local government representees, party organizers, workers and strong candidates” to compensate for its lack of broader popular appeal[24]. This indicates PML-N’s strategy acknowledges its deficit in mass popularity and instead focuses on grassroots machinery to get out the vote. However, in an environment where PTI has an enthusiastic wave, these old-style tactics may not suffice. A mediocre PML-N candidate with only biradari backing may lose if PTI’s brand power mobilizes a larger turnout against them. Moreover, a number of PML-N’s traditional political families have splintered or even defected over time (some joined PTI or went neutral), weakening the network.

Another cultural factor is that PML-N’s image has taken a hit among the urban middle class due to corruption cases and governance criticisms. While PML-N loyalists dismiss many charges as politically motivated, the constant news of trials and convictions (e.g., Nawaz Sharif’s past conviction, cases against Shahbaz Sharif’s family, etc.) has tarnished its reputation for a segment of voters that values integrity. PTI has effectively used this in their narrative, painting PML-N leaders as corrupt “mafias” vs PTI’s supposedly cleaner record. Even though corruption is an issue that cuts across parties in reality, PML-N has been on the defensive in the court of public opinion on this front. For Lahore’s more informed citizens, this matters – they recall incidents like the Panama Papers that implicated Nawaz Sharif, or the scandals of the previous government, which reduces enthusiasm for PML-N’s return.

Furthermore, the current leadership of PML-N lacks the charisma to galvanize supporters in the way Imran Khan can for PTI. Nawaz Sharif, now an elder statesman, did return to Pakistan in late 2023, which briefly boosted PML-N morale. However, health issues and legal challenges limited his active campaigning. The day-to-day campaign burden has fallen on figures like Maryam Nawaz (Nawaz’s daughter) and Shahbaz Sharif (Nawaz’s brother, former CM), who, while prominent, have not significantly broadened the party’s appeal beyond existing loyalists. Maryam Nawaz does draw crowds and especially tries to engage women voters for PML-N, but the survey suggests it has not moved the needle much yet. PML-N’s narrative heavily touts its past development projects (“we built your roads, metro, ended load-shedding, etc.”) and the promise of stability/experience. Yet, when people are undergoing an economic squeeze, promises of stability ring hollow. The cultural expectation in Pakistan that incumbents will patronize their base has also backfired; many PML-N voters feel they did not receive much benefit during the party’s recent time in federal power due to the economic crunch.

The Survey shows that Maryam Nawaz Sharif has better approval rate in governance category.

Geographically within Lahore, PML-N’s support is now largely concentrated in a few areas rather than citywide. Historically, north Lahore (older parts of the city, more lower-income and dense communities) was a PML-N bastion, and inner-city neighborhoods around the walled city and old marketplaces have deeply ingrained PML-N loyalties. The survey hints that PML-N still holds some ground in these interior localities – indeed “interior Lahore is still a stronghold of PML-N”, though even there PTI has made gains[26]. Peripheral areas on the city’s edges (sometimes called border or rural fringes of Lahore) also used to favor PML-N due to biradari ties and conservative mindset; PML-N remains “strong” in some border areas but PTI is competitive even there now[27]. In contrast, southern and central Lahore, which include many newer developments and middle-class housing societies, have swung hard to PTI[28]. This means PML-N is fighting to retain only portions of its old territory, essentially trying not to be completely swept away. The party might draw comfort that in a first-past-the-post system, even 40% vs 50% in a constituency can potentially yield a win if they mobilize better, but a citywide 16% is indicative of losing many seats if PTI voters turn out.

In summary, PML-N’s low support in this poll is a reflection of both its current unpopularity due to governance failures (notably the economy) and longer-term shifts that have eroded its urban appeal. The party still has a core base – older voters, some traders, loyal networks in old Lahore – but that core is shrinking and isolated. PML-N’s reliance on traditional politics of patronage is proving insufficient against PTI’s populist wave and issue-based appeal. For PML-N to rebound, it would need to both energize its base and win over undecided moderates, likely by addressing economic grievances swiftly and presenting a compelling forward-looking agenda. The survey indicates that as of now, those efforts have not been enough, and time is running short for the party to alter the perception that it is out of touch with the average Lahori’s aspirations.

Lastly, the fundamental issue with PMLN is that majority of the people do not consider them as their representatives in the governments. Despite, Maryium Nawaz Sharif is trying her best to restore the popularity of PMLN: however, the people are more interested in genuine representation, rights and rule of law than projects, development and even provision of services.

Minor Parties and Their Niche Support

While PTI and PML-N dominate the political discourse, several minor parties do maintain a niche presence in Lahore’s political arena. The survey numbers for these parties – TLP at 5%, PPP at 3%, JI at 2% – may be small in absolute terms, but they are worth examining both for what they represent and for their potential impact on close races.

Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP), polling 5% in this survey, is an Islamist party that rose to prominence in the last decade by championing the defense of blasphemy laws and rallying against any perceived softening on that issue. TLP’s base is largely among Barelvi Sunni Muslims, particularly the lower-middle class and urban poor who are motivated by religious sentiment and issues of Namoos-e-Risalat (the honor of the Prophet). In Lahore, TLP showed its street power in 2017–18 with massive sit-ins and protests, and it translated some of that into votes in 2018, coming in third in many city constituencies. A 5% citywide support now suggests that TLP retains a foothold. Likely hotspots for TLP in Lahore are areas with a concentration of madrassahs or religious voters – for example, parts of north Lahore or outskirts where the party’s firebrand rhetoric against “blasphemers” and its positioning as a defender of the faith find resonance. Culturally, TLP taps into a strain of populist religiosity. It does not have the polished manifesto of a mainstream party, but it offers an identity and community to those who feel other parties are either too liberal or too elitist. TLP’s leader, Saad Rizvi, is actually rated as the third most popular leader in Punjab in an earlier Republic Policy survey (after Imran Khan and Nawaz Sharif)[29], reflecting that his name recognition and appeal extends beyond just the voters who would ultimately choose TLP. However, under Pakistan’s first-past-the-post system, TLP’s 5% vote share in Lahore is unlikely to win seats outright – what it can do is play spoiler. In a tight PTI vs PML-N race, a few thousand votes for TLP might swing the outcome by splitting the conservative vote. Both major parties are aware of this; PML-N in particular sometimes courts TLP voters indirectly or at least tries not to alienate them, whereas PTI positions itself as moderately religious but not extremist, hoping to attract those same voters. The 5% figure indicates that TLP has a committed fringe following that will show up, though it is a fringe in the larger picture.

The Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), once one of Pakistan’s two biggest parties, has withered in Punjab over the past two decades. This Lahore survey shows PPP at 3% support, which is consistent with its poor performance in recent elections here. PPP’s decline in Lahore can be attributed to multiple factors: the rise of PTI consumed the anti-PML-N space that PPP might have occupied; the Bhutto charisma that once enthralled urban voters has faded with new generations; and PPP’s leadership (Asif Ali Zardari and now Bilawal Bhutto Zardari) have focused their efforts on Sindh province where the party is strongest, effectively ceding Punjab to rivals. The 3% who still back PPP in Lahore likely include some old party loyalists – families that supported Zulfikar Ali Bhutto or Benazir Bhutto in the past and have stuck with the party out of loyalty to its left-of-center, populist roots. Additionally, PPP has pockets of support among certain communities: for instance, some Christian and other religious minority voters trust PPP’s relatively secular and minority-friendly stance over the more religiously oriented PML-N or PTI (this was evident in by-elections where PPP actively reached out to Christian neighborhoods[17]). There may also be some labor or low-income communities in Lahore who recall PPP’s slogan of “bread, clothes, shelter” and land reforms – essentially viewing it as the party of the underprivileged. However, with only 3%, PPP is not a major contender in any Lahore constituency on its own. The party has occasionally struck vote adjustments with PML-N in Punjab to avoid splitting the opposition vote, but given PPP’s limited presence, its impact is minimal. For the upcoming elections, PPP might concentrate on a couple of provincial assembly seats in Lahore at best, and otherwise serve more as a coalition partner to PML-N in federal politics rather than a direct competitor.

Jamaat-e-Islami (JI), at 2% in this poll, represents the orthodox Islamist vote in Lahore. JI is a cadre-based party with an emphasis on Islamic ideology and social welfare. It has a long history – JI was once influential in Karachi and had a presence in Lahore’s municipal politics, and it still runs welfare organizations and schools. The 2% support suggests that JI’s core in Lahore is intact but very small. These are likely hardcore Jamaat families, possibly in areas like Ichhra or other places where JI historically had support, and among some educated Islamist professionals. JI’s low number is partly due to the fact that many religiously inclined voters have alternatives now (like TLP on the Barelvi side or even PTI which has a mix of religious rhetoric). JI also suffered because it stayed out of the mainstream for a while (boycotting the 2008 elections, for example, which diminished its relevance). In recent times, JI has repositioned as an anti-corruption, clean politics voice (it ran an anti-inflation campaign in 2023) but it hasn’t translated into votes. The party is known, however, for its disciplined supporters – that 2% will almost certainly go vote, come what may. JI could matter in a tight race if it pulls a chunk of votes that might otherwise go to PTI (since some JI voters overlap ideologically with PTI’s conservative side). There have been instances where PTI and JI formed electoral alliances (e.g., in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in the past), but in Lahore no such alliance exists currently, so JI will run independently.

The “Others” portion, which combined with undecided is 23%, probably includes any remaining small parties or independents. Aside from IPP (mentioned earlier), others might include very small local Punjabi parties or independents with strong biradari influence in a locality (for instance, a local notable who runs as independent). None of these have more than a fraction of support citywide. However, collectively, the presence of minor parties like TLP, PPP, JI, etc., indicates that about 10% of Lahore’s electorate prefers options outside the PTI/PML-N binary. This is not insignificant – in a truly tight race between two giants, even that 10% can be kingmakers if their voters swing behind one major party in a second preference or tactical vote scenario. But if the PTI vs PML-N gap stays as large as it is now, these smaller parties will mainly serve to demonstrate the pluralism of voter sentiment without drastically altering outcomes.

In conclusion, minor parties in Lahore each cater to a specific niche – be it religious hardliners (TLP, JI) or old-school populists (PPP) – but none currently threaten the dominance of the big two. Their significance lies in local dynamics: for example, a TLP candidate might cause an upset in one provincial constituency by taking votes from a PML-N candidate, or PPP might join an alliance that secures a few extra percentage points for a coalition. The Republic Policy survey confirms that the political landscape is heavily polarized between PTI and PML-N at the macro level, with the rest playing more of a supporting or spoiler role rather than leading roles.

The High Undecided Vote: Uncertainty and Implications

Perhaps one of the most consequential findings of the survey is the high proportion of undecided voters, which together with “others” accounts for 23% of respondents. This means nearly one in four potential voters in Lahore has not firmly aligned with any party as of July 2025 (or at least did not disclose their preference). In political analysis, an undecided bloc of this size is significant – it introduces a large element of uncertainty and opportunity in the lead-up to the election. Understanding who these undecided voters are and what might sway them is crucial for both PTI and PML-N as they strategize for the campaign.

One reason for the high undecided percentage could be the volatile and intimidating political environment of the past year. With PTI facing a crackdown (including arrests of key figures and restrictions on media coverage), some supporters may have been reluctant to openly state their voting intentions. Even in an anonymous survey, a cautious voter might withhold their true preference, especially if they fear repercussions or simply feel uncomfortable voicing it. PTI leaders claimed that conditions in early 2024 were so repressive that their supporters faced harassment during elections[15]. Although the survey was conducted in 2025 when the climate might have somewhat improved, residual fear could persist among the populace. Thus, it’s plausible that a portion of the “undecided” are actually silent PTI leaners who chose not to declare their support to a pollster. If true, PTI’s real backing could be even higher than 51%, and many of those undecideds might break toward PTI in the privacy of the voting booth. This is analogous to the well-known “silent voter” or “shy voter” phenomenon in polling, where voters do not reveal their true intent due to social or political pressures.

Another segment of the undecided voters likely consists of genuinely ambivalent individuals who are dissatisfied with both major parties. These could be people who voted PML-N in the past but are unhappy with inflation and governance, yet they are still not fully convinced by PTI either (perhaps due to memories of PTI’s own inflation period or discomfort with PTI’s confrontational style). Likewise, there might be first-time voters or politically lukewarm citizens who haven’t followed politics closely and thus haven’t made up their mind. For such voters, the campaign period will be critical. Their stance might depend on factors like: the candidates nominated in their constituency (a likeable local candidate can swing an undecided voter), the manifesto promises, or even how the economic situation evolves in the weeks before the election. Given that Pakistan’s economic condition is dynamic, an undecided voter could be swayed if, say, the government manages to temporarily lower fuel prices or if PTI presents a credible economic recovery plan – essentially, issue-based swings.

The large undecided pool also reflects a degree of public cynicism and wait-and-see attitude. Many Pakistanis have seen governments come and go without fundamental change in their lives, leading to disenchantment. It would not be surprising if some respondents answered “undecided” or “no preference” as a way of saying “none of the above satisfy me.” This is especially plausible for those who might lean towards third parties or independents but know that those have little chance to win – instead of naming a minor party, they just say undecided. It’s an expression of political alienation in some cases. The implication is that voter turnout could be affected by this sentiment; if a significant chunk remains undecided up to election day out of apathy or frustration, they might simply not vote at all. Conversely, if something or someone inspires them, they might turn out in force for whichever option they decide is the lesser evil or the more hopeful.

From a campaign strategy perspective, both major parties will be targeting these undecided voters intensely. For PTI, the goal would be to convert the undecideds by reinforcing the narrative that “all other parties have failed you, give us a full chance” – essentially persuading skeptics that PTI deserves another shot and that Imran Khan’s troubles were due to standing up for the people. PTI will also likely highlight any new faces or technocrats in their team to assure the undecideds (especially moderate and educated ones) that governance will improve. For PML-N, the undecided bloc is perhaps their only hope to close the gap with PTI. They would aim to win them over by stoking fears of instability if PTI returns, reminding voters of any positives from PML-N’s past (e.g., infrastructure, experience), and possibly by offering short-term relief measures (like subsidies or development funds announced for Lahore) to show responsiveness. PML-N’s challenge is greater: as Republic Policy’s analysis notes, “PML-N faces multiple political and electoral challenges and their foremost challenge is to influence young voters”[25] – many of those young voters are currently sitting in the undecided camp or soft-PTI camp. PML-N would need to rebrand or substantially change its image to attract them, which is tough to do within a few months of campaigning.

The high undecided percentage also raises the stakes for the final days of campaigning and electoral dynamics. As political strategists often say, polls are a snapshot, and many voters truly make up their minds very late. Republic Policy’s own commentary on constituency politics in Pakistan emphasizes that “even the last few days are critical, where voters may change their opinion due to the interests of the constituency politics.”[30] In Lahore, that could mean that local developments – like endorsement of one candidate by a local community leader, or a compelling last-minute rally – could tip undecided individuals. The influence of biradari (kinship groups), while generally weaker in Lahore, might still play a role for undecided voters who will ultimately vote along family or community recommendations if they stay undecided until the end. Moreover, the undecided bloc ensures that nothing is absolutely guaranteed; if, hypothetically, most undecideds broke for PML-N, the gap with PTI would narrow considerably (it’s unlikely enough to overturn a 35-point gap, but it could reduce PTI’s margin). Alternatively, if a large share of undecideds lean towards PTI or other anti-incumbent options as a protest vote, PML-N could be left even more diminished.

Finally, it’s important to consider the implication for democratic legitimacy and engagement. A large undecided segment means that there is a lot of space for political engagement in the coming months. It suggests that voters are open to persuasion and are paying attention. This can be healthy if it leads to parties addressing voter concerns to win them over. However, it can also be perilous if the undecided are swayed by misinformation or short-term bribes (vote-buying, which unfortunately is not unheard of in local Pakistani elections). The onus is on civil society and media to help voters make informed choices rather than purely emotional or transactional ones. Republic Policy’s public interest mandate would suggest that engaging these undecided citizens with facts, debates, and policy options is crucial so that their eventual decision – whichever way it goes – is an informed one that strengthens democratic accountability.

In conclusion, the 23% undecided/others statistic is a double-edged sword: on one hand, it indicates that PTI’s lead, while very strong, is not unassailable if PML-N can make inroads into that group; on the other hand, it also indicates that a lot of Lahoris remain unconvinced by the current political offerings, which is a sobering sign for the political class. These voters will effectively decide how big PTI’s victory margin is or whether PML-N can somewhat recover. They make the upcoming campaign period incredibly critical. All parties should heed that high undecided number as a call to address voter issues more earnestly – because nearly a quarter of the electorate is essentially saying “we’re waiting to be convinced.”

Comparative Insights from Previous Republic Policy Surveys

The trends observed in the July 2025 Lahore survey did not emerge in a vacuum – they are part of evolving political currents that Republic Policy and other analysts have been tracking in recent years. Comparing this survey’s findings with previous Republic Policy articles and surveys provides valuable context and shows how public opinion has shifted over time.

One key reference point is the Republic Policy constituency-based survey of Lahore conducted in October 2023, ahead of the then-expected general elections. That survey, which had a larger sample (over 6,800 respondents) and was organized by National Assembly constituency, had already highlighted a strong surge for PTI in Lahore. It found that PTI was leading in about half of Lahore’s constituencies outright, and running neck-and-neck with PML-N in most of the rest, while PML-N led comfortably in very few[11]. Essentially, the writing was on the wall that Lahore was undergoing a political realignment. The current 2025 survey confirms and amplifies that trend – what was a strong lead in constituencies has translated into an absolute majority in overall voter preference for PTI. One reason the PTI lead has grown even larger now could be the performance (or perceived non-performance) of the PML-N-led government in the intervening period. The earlier survey was taken when PML-N had just taken power as part of a post-Imran interim setup, and some voters might have still given benefit of doubt or had nostalgia for PML-N. As the economic situation worsened through 2024, more voters shifted firmly into the PTI column.

The province-wide survey of Punjab by Republic Policy in late 2023 also offers comparative insight. It concluded that Imran Khan was the most popular leader in Punjab, followed by Nawaz Sharif, with TLP’s Saad Rizvi a distant third, Bilawal Bhutto fourth and JI’s Siraj-ul-Haq fifth[29]. Lahore’s July 2025 survey mirrors this province-wide ranking closely: PTI (Imran’s party) is first, PML-N (Nawaz’s party) second, TLP third, PPP fourth, JI fifth in the city’s preferences. This shows a consistency between Lahore and wider Punjab in terms of relative popularity – albeit Lahore seems to lean even more heavily toward PTI than some other parts of Punjab might. In any case, the earlier finding underscores that PTI’s ascendancy is not just a Lahore-specific fluke but part of a broader Punjabi trend, and that PML-N’s struggles are widespread. It also reinforces that smaller parties like TLP and PPP, while present, are way behind the big two in mass appeal.

Looking back further, historically Lahore was a PML-N stronghold as noted – PML-N dominated here in the 2013 and 2018 elections. The fact that by 2025 PML-N is polling only 16% is a remarkable decline. There are some parallels one might draw: for example, in the 1970 election (pre-partition West Pakistan), urban voters massively swung to new parties (like PPP at the time) rejecting the old Muslim League – Lahore went with Bhutto’s wave then. Today, one could analogously say Lahore has shifted from the “modern Muslim League” (PML-N) to a new force (PTI) in a wave of discontent with the status quo. Republic Policy’s editorial voice has often emphasized the need for responsive governance and reforms, and the survey trends reflect public demand for the same. Articles discussing issues like government accountability, economic transparency, and youth empowerment set the stage for why PTI’s messaging might be hitting home with Lahori audiences (because PTI at least talks that talk). Meanwhile, Republic Policy’s analysis of PML-N’s governance – for instance, critiques of how the Punjab government managed finances or the perception of misuse of authority – may help explain why the middle class drifted away from PML-N[14].

It’s also worth noting a comparative insight on voter priorities. Earlier Republic Policy reports indicated that “even in Lahore, most people will still vote on inflation”, meaning economic pain is the top issue, while an educated class also values democracy and rule of law[16]. Comparing that to now, it appears to hold true: inflation (and the broader economy) has indeed been the Achilles heel for PML-N, driving voters toward PTI, and talk of justice/rule-of-law has been PTI’s rallying cry attracting the educated segment. This alignment of issues with voter movement is exactly as predicted in prior analyses.

Finally, one comparative point can be made about electoral dynamics: the earlier Republic Policy survey stressed that having the PTI symbol on the ballot and a fair process was a baseline assumption for their predictions[12]. In reality, by 2024, PTI faced hurdles (Imran Khan’s disqualification, many candidates running as independents, etc.). The current survey question phrased “if elections are held in July 2025” and presumably allowed people to assume all parties are running normally. The implication is that public sentiment is one thing, but translating it to actual seats depends on the electoral context. This has been a recurring theme in Republic Policy’s writing – that surveys measure political trends, but actual election results are the final judgment of the people’s will[31], subject to last-minute changes and the fairness of the process. The comparison between survey and actual outcome (for instance, if one compares pre-election polls to the contested 2024 election results where PTI hardly won seats due to the crackdown) shows a discrepancy that can arise from external factors. Going forward, the 2025 survey will set a benchmark: if a free and fair election occurs, one would expect results akin to the survey (PTI winning Lahore handily). If not, differences would be scrutinized.

In summary, previous Republic Policy surveys and analyses provide a backdrop that makes the 2025 Lahore findings unsurprising – they are part of a larger trend of PTI gaining and PML-N waning in Punjab, driven by youth and urban dissatisfaction and economic grievances. The consistency of findings (Imran vs Nawaz popularity ranking, etc.) lends credibility to these results. However, history also teaches us that public opinion can shift if circumstances change; PML-N’s dominance in one era gave way to PTI’s dominance now, and nothing says it couldn’t shift again in the future. The comparative lens simply highlights that Lahore’s voters in 2025 are in a very different mood than they were a decade ago, reflecting Pakistan’s changing political narrative.

Eighty Seven 87 percent of Lahoris believe that 2024 elections were rigged:

Conclusion

The July 2025 Lahore voting intentions survey by Republic Policy paints a clear yet complex picture of the political climate in Pakistan’s second-largest city. PTI’s lead in Lahore is commanding, with a majority of respondents indicating support for Imran Khan’s party. This suggests that if elections were held today under free conditions, PTI would likely sweep Lahore – an outcome that would have been unthinkable for PML-N loyalists just a few years ago. The survey attributes this lead to strong youth support, cross-sectional appeal cutting across social classes, and the prevailing anti-incumbency sentiment fueled by economic distress. In contrast, PML-N’s support has shrunk drastically, confined to pockets of older voters and traditional networks that are proving insufficient against the PTI wave. The party faces a formidable challenge to reinvent itself and reconnect with a populace that appears to be demanding a break from the past. Smaller parties like TLP, PPP, and JI, while present in the political arena, currently play more of a peripheral role – their support bases are too limited to challenge the PTI/PML-N duopoly in Lahore, though they remain relevant in specific niches and could influence close contests.

The high percentage of undecided voters (23%) is a crucial wild card. It injects a dose of uncertainty – a reminder that surveys are snapshots, not destiny. These undecided citizens hold considerable power in their hands: they could either cement PTI’s lead further or give PML-N a chance to close the gap, depending on which way they lean as the election approaches. Their indecision reflects both the volatile political environment and perhaps a yearning for better choices or more information. How the parties engage with this segment – through policy offers, campaign messaging, and on-ground outreach – may well determine the final electoral outcome in Lahore beyond what the raw numbers currently suggest.

From a broader perspective, this survey’s findings underscore a democratic vitality in Pakistan’s urban politics – voters are not beholden to one party permanently; they are evaluative and willing to shift when performance falters. Lahore’s electorate is asserting its agency by gravitating towards the party it believes can deliver change, and by withholding support from those it feels have fallen short. This bodes well for accountability: politicians cannot take Lahore for granted. At the same time, the importance of a fair electoral process cannot be overstated. The survey operates on the assumption of a level playing field; it is imperative that the actual election does too, so that the genuine “will of the people” is reflected[31]. Free, transparent elections – as Republic Policy often advocates – are the only way to translate such public opinion into legitimate governance.

In conclusion, Lahore’s political winds in mid-2025 strongly favor PTI, but with an election on the horizon, both opportunity and risk abound. PTI will aim to solidify and convert its support into a decisive victory, while PML-N will fight to regain trust and prevent a rout. The large pool of undecided voters means neither can be complacent. For the citizens of Lahore, the survey is a mirror of their current hopes and frustrations. It is an evidence-based snapshot that contributes to an informed public discourse – exactly what Republic Policy strives for in the public interest. As the campaign heats up, one hopes that all stakeholders focus on issues and reforms that matter to people’s lives, so that whichever way this volatile electorate ultimately goes, Pakistan’s democracy emerges stronger. The final verdict, as always, will rest with the voters themselves, exercising their right in the ballot box to shape the country’s future.

Survevys only show the intentional trends and primary data so that policies, schemes and plans can be carved out. The final analysis of the survey report.

Follow Republic Policy on social media for more insights and updates:

- Website: republicpolicy.com

- YouTube: RepublicPolicy

- Facebook: RepublicPolicy

- Twitter (X): @RepublicPolicy

- Instagram: @republicpolicy

- LinkedIn: RepublicPolicy Think Tank

- TikTok: @republic_policy

[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [16] [18] [19] [20] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [30] [31] A Report on the National Assembly Survey of Lahore District – Republic Policy

This is a survey report of 2023 by Republic Policy Think Tank.

[9] [15] [17] [21] [22] PP-52 By-Election: PML-N Maintains Edge Amid Tight PTI Challenge – Republic Policy

[29] Republic Policy Survey Reveals Imran Khan the most Popular Leader of Punjab – Republic Policy