Barrister Danial Mujtaba

The administrative centralization is unique in Pakistan. The center can control the provinces by appointing six chief secretaries and IGs. Hence, it is the most unique model of the centralization as it makes provincial assemblies, cabinets and chief ministers irrelevant.

The existing mode of appointment of chief secretary is an administrative riddle extending a colonial custom. It comprises a consultative process between the prime minister and the chief minister or their authorized persons. This arrangement purely depends upon an agreement supposedly reached between the federation and provinces in the early part of independence. This agreement is the foundation of creating the civil service of Pakistan CSP and subsequent composition and cadre rules in 1954. Section 15(4) of the ibid agreement governs the process of appointing a chief secretary. The ibid section of the agreement lays down the process of appointing a chief secretary, where due consideration shall be given to the proposal of the provincial government. However, the final decision to appoint a chief secretary shall be the discretionary power of the federal government. Hence, undoubtedly, the federal government manoeuvres the mode of appointment to her advantage on a post purely connected with the affairs of a province.

However, this mode of appointment, depending merely upon an agreement, requires serious legal and constitutional interrogation. Does the so-called agreement correspond to the provisions of the existing scheme of the Constitution? Inherently, the 18th amendment of the Constitution has separated the legislative, executive and financial authority of the federation and provinces, thus making the present mode of appointment a constitutional challenge to the 18th amendment. How can the federal government extend its executive authority on a provincial post bearing the provincial legislative, executive and financial authority?

Historically, the office of chief secretary was established in colonial India to lead the administration in a province in the absence of an empowered political executive. Therefore, it was only accountable to the secretary of state for India. Indian partition act of 1947 deleted all the provisions regarding the services of the secretary of state for India. This deletion of the services should have allowed newborn countries to raise services corroborating the scheme of new constitutions. Unfortunately, the dominion of Pakistan could not legislate the Constitution. So, amid constitutional crises, a new service modelling on the colonial scheme of reserving provincial posts for central services was established by manoeuvring of centralists.

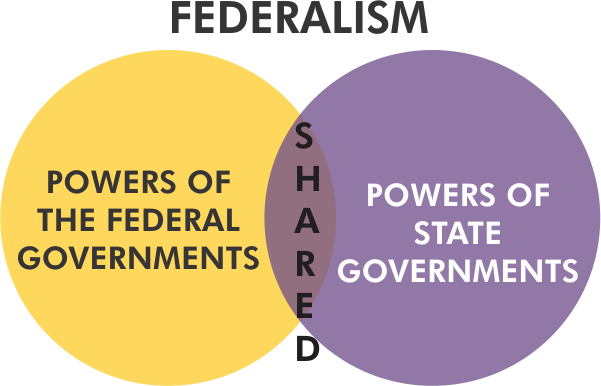

Pakistan is a federal parliamentary constitution. Powers in a federation are distributed between federation and provinces, whereas a parliamentary form of governance produces the executive from the same legislature. The executive is the functional and implementing part of a government, either political or bureaucratic. In democracies, it is the political executive who leads the bureaucratic executive. The political executive is the elected executive, unlike the bureaucratic executive, which is the permanent part of the executive. No provision of the Constitution nor legislation can take effect in defiance of the federal parliamentary nature of the Constitution. it raises a fundamental constitutional question if the political executive of the province is produced by the provincial assembly, then how can the bureaucratic head be produced by the federal government? It simply requires that the same legislature must produce both the chief minister and chief secretary of a province.

The argument draws a question of who is constitutionally competent to appoint a chief secretary. The post of chief secretary is neither federal nor a common post between the federation and a province. It is a post connected with the affairs of a province in connection with Article 240 (b) and Provincial civil servants’ acts. The executive, legislative and financial authority of the federation cannot extend to the post of chief secretary bearing provincial legislative, executive and financial authority. The provincial government is constitutionally competent to appoint the chief secretary from the service of the province. The present mode of appointment by the federal government through the disputed agreement violates the fundamental principles of the Constitution.

It is necessary that provincial governments may enforce their constitutional prerogative to appoint a chief secretary. The appointment by the provincial governments shall benefit the provincial administrative autonomy. The incumbent chief secretaries are federal civil servants and, therefore, not answerable to provincial governments. The federal government not only appoints a federal civil servant to a provincial position of chief secretary but also places a number of federal civil servants at the disposal of provincial governments. The chief secretary leads the battalion of federal civil servants who make a monopoly in the provinces compromising provincial interests.

The appointment of a Chief secretary requires a constitutional alignment. The political and bureaucratic executive must correspond to the same legislature in parliamentary governance. How is it possible that a provincial assembly create a chief minister, but a chief secretary is not created by it? There is a need to rectify this constitutional anomaly.

The executive part of the government should correspond with each other. These constitutional and administrative anomalies lead to the failure of governance and federalism. There is no model of governance available in the world where the top bureaucratic executive is not accountable to the political executive. Provinces have long suffered from this scheme of reserving provincial posts for central services, and there is an urgent need to corroborate it with the Constitution. The best start will be to appoint a chief secretary by the provincial governments from the services of the provinces.

Apart from constitutional anomalies, a parallel office to that of the Chief Minister is also administratively not required in a cabinet form of governance. The chief minister must remain the sole chief executive of the province. The forces of centralization should realize the importance of devolution in a federal form of governance. Provincial governments are required to appoint their chief secretaries in order to ensure governance and service delivery.

Lastly, the post of chief secretary is a post connected with the affairs of a province. It has provincial, executive and financial authority, and it can only be exercised by the provincial chief minister, cabinet and assembly. The same is the case with the Inspector General of Police IGP. Therefore, the spirit of administrative federalism and the 18th amendment needs to be implemented in Pakistan to ensure administrative federalism and governance.

Please, subscribe republicpolicy.com