Ahmed Javaid

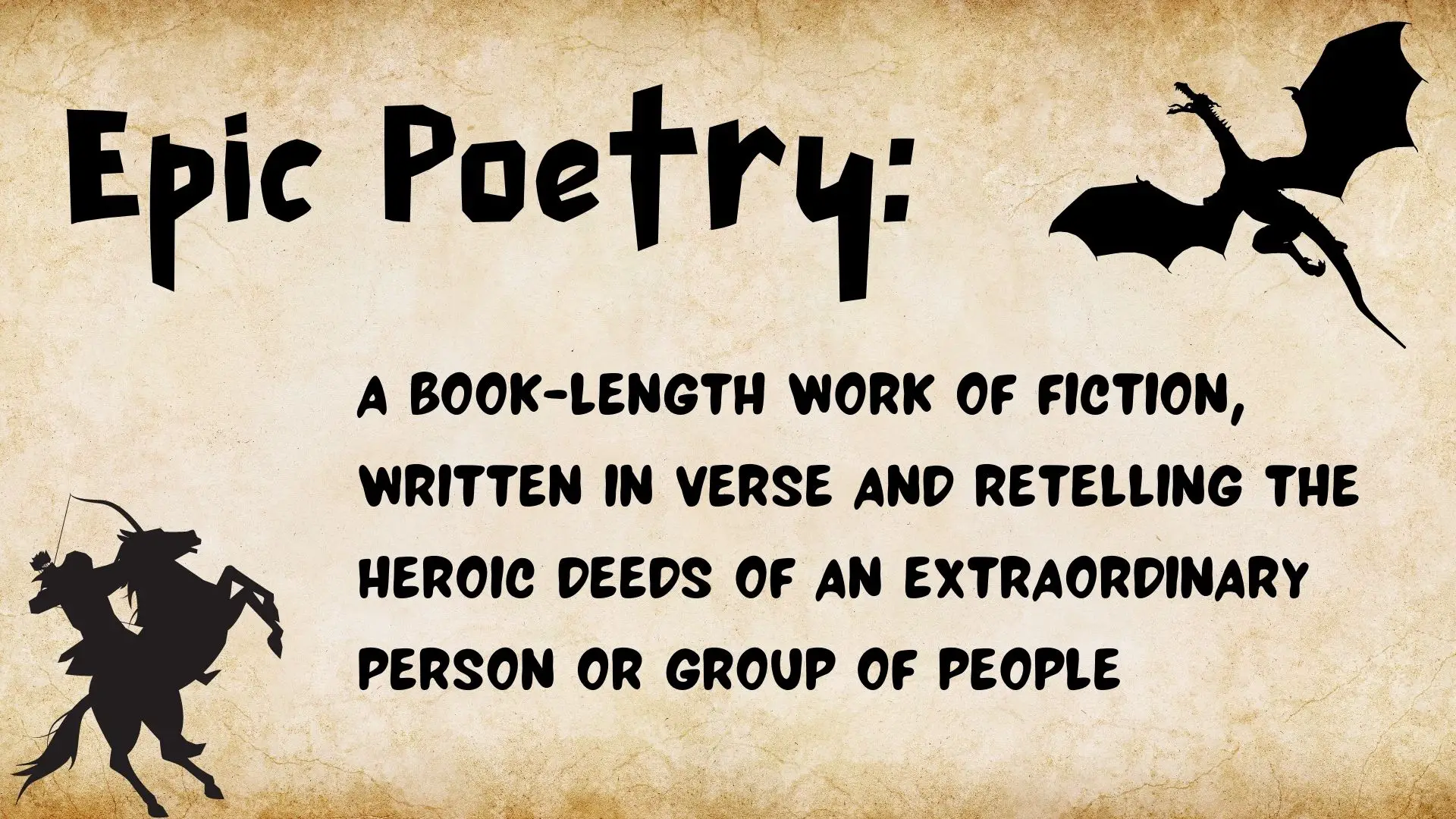

Epic poetry, a universal form of storytelling, transcends cultural and temporal boundaries. While the term ‘epic’ is often associated with lengthy narrative poems, it also encompasses novels and motion pictures. In the realm of literature, epic compositions can be both oral and written. The oral tradition, exemplified by Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, involves the transmission of stories through speech and memorization. Written examples of epic poetry include Virgil’s Aeneid, Chanson de Roland, and John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

Epic poetry, a vast and diverse genre, encompasses myths, legends, histories, religious tales, and moral theories. It serves as a conduit for cultures to preserve and pass down their traditions. In societies with a heroic age, epic poetry was a powerful tool to inspire warriors, celebrate their deeds, and ensure the perpetuation of their achievements. These epic poems, often centered around national heroes and their legendary narratives, played a pivotal role in transmitting cultural values and ideals across generations, underscoring the profound significance of this art form.

In heroic-age societies, epic poetry played a crucial role in honoring noble warriors and their illustrious ancestors, serving as a model of ideal heroic behavior. These epic poems were recited in banquet halls and before battles, significantly influencing the morale of the warriors. These traditions were intricately linked to the aristocratic families, often conveying genealogies and the preservation of family honor.

With the waning of the heroic age, the epic tradition often transitioned to the popular oral tradition, where the old songs persisted as a form of entertainment among the people. This popular tradition, however, was distinct from the tradition that was once integral to the culture of the nobility. The advent of literacy eventually led to the decline of oral epic traditions, as the role of the oral singer diminished, and the tradition lost its power of renewal. This transition marks a significant shift in the cultural landscape, underscoring the transformative power of literacy.

The ancient Greek epic serves as an example of the life cycle of an oral tradition. Originating in the late Mycenaean period, Greek epic poetry outlasted the downfall of the heroic-age culture and maintained itself through the “Dark Age” before reaching its climax in the Homeric poems. The transition from aoidoi to rhapsodes marked a shift in the practice of epic recitations, eventually leading to the decline of the oral epic tradition in ancient Greece.

Greek Epic:

The Greek epic may have been heavily influenced by Asian traditions during its formative stage, particularly as the late Bronze Age Greek world had close ties with the Middle East and formed an integral part of the Levant. Greek merchants were present in locations such as Ugarit and Alalakh, and had continuous diplomatic relations with the Achaeans of Greece. It is not surprising that Greek myths have parallels with Hittite and Hurrian myths, as evidenced in the Theogony of Hesiod and elsewhere. The Epic of Gilgamesh was well-known in the Levant, and the Odyssey has many parallels with it, such as Gilgamesh’s encounters mirrored in Odysseus’ journey. The Iliad also shares similarities with the friend of Gilgamesh, Enkidu.

If these are indeed borrowings, it is remarkable that they are used in Homer to express a view of life and a heroic temper radically different from those of the Sumerian epic of Mesopotamia. The Greek heroic view of life is derived from an Indo-European notion of justice, where each being has a fate (moira) assigned to them, and human energy and courage should be spent in bearing it with style, pride, and dignity. This contrasts with the Mesopotamian view, which expresses deep human regret at mortality. The Iliad and Odyssey present noble and tragic figures who endure their fates with courage and moderation.

Furthermore, the personalities and deeds of figures in Greek mythology, such as Agamemnon, Achilles, and Hector, illustrate the consequences of exceeding the proper limits of the human condition, resulting in divine retribution. In the Homeric epics, the characters struggle to fulfill their destinies and face the repercussions of their actions, portraying a unique perspective on heroism and mortality.

In comparison, Hesiod’s Theogony and Works and Days convey a similar basic conception of justice to the Homeric epics, despite their differences in style and subject matter. They depict a world order in which humanity’s lot is assigned by Zeus and emphasize the importance of observing moira without committing excesses. The myths in the Works and Days illustrate the idea that humans must work hard and endure suffering as part of their fate, alluding to the consequences of deviating from the boundaries set by the gods. This portrayal of justice and the human condition is a recurring theme in both the Homeric and Hesiodic epics, illustrating a shared cultural perspective in ancient Greek literature.