Sarah Khan

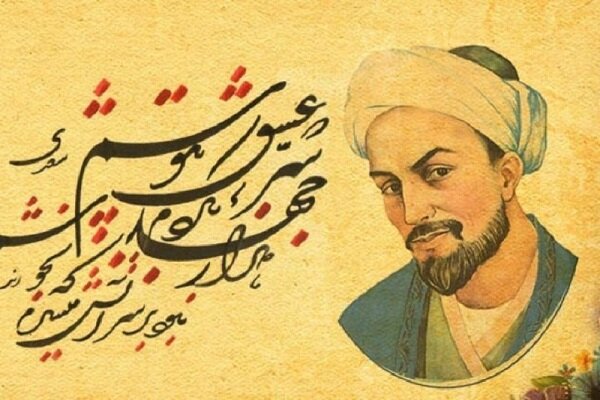

Saadi Shirazi, known as Saadi of Shiraz, was a prominent Persian poet and prose writer of the medieval period. He is celebrated for the high quality of his writings and the profound social and moral thoughts he conveyed. Regarded as one of the greatest poets of the classical literary tradition, Saadi earned the nickname “The Master of Speech” among Persian scholars and has been quoted in Western traditions as well. His book, Bustan, was ranked as one of the 100 greatest books of all time by The Guardian.

Born in 1210 in the city of Shiraz, Saadi’s exact birth date remains uncertain. Little is known with certainty about his life, and there are discrepancies in details about his name and lineage. His given name, honorific, agnomen, and patronymic are spelled in various ways in different sources. The uncertainty surrounding his full name has led to different interpretations by scholars.

Saadi’s best-known works, Bustan completed in 1257 and Gulistan completed in 1258, showcase his literary talent. Bustan is a collection of stories illustrating virtues recommended to Muslims and reflections on the behavior of dervishes, while Gulistan is mainly in prose and contains stories and personal anecdotes interwoven with short poems. Saadi’s profound understanding of human existence, as evidenced in his writings, and the contrast between the fate of those dependent on kings and the freedom of the dervishes, is a source of enlightenment for his readers.

In addition to Bustan and Gulistan, Saadi was also a panegyrist and lyricist, known for his odes portraying human experiences. He is considered one of the greatest ghazal-writers of Persian poetry alongside Rumi and Hafez. Saadi’s famous aphorism “Bani Adam” from the Gulistan calls for breaking down all barriers between human beings, emphasizing the interconnectedness and empathy among people.

Overall, Saadi’s literary contributions have left a profound impact, earning him recognition as a masterful poet and a profound thinker whose works continue to be celebrated for their timeless wisdom and insight into the human condition. Saadi’s ability to perceive and articulate the spiritual and practical aspects of life is a central theme in his writings. In his work “Bustan,” he harnesses the everyday world to transcend earthly boundaries, employing delicate and soothing imagery to convey spiritual messages. Conversely, in “Gulistan,” he brings the spiritual down to earth to touch the hearts of his readers through vivid and concrete imagery with a palpable truthfulness. This dichotomy in Saadi’s approach realistically reflects the different experiences of individuals such as the Sheikh preaching in the Khanqah and the travelling merchant passing through a town. What truly sets Saadi apart is his embodiment of both the Sufi Sheikh and the traveling merchant, as he beautifully expresses in his own words—the two almond kernels in the same shell.

Saadi’s prose style is a paradox, described as both simple and impossible to imitate, flowing naturally and effortlessly. Its simplicity is underpinned by a complex semantic framework comprised of synonymy, homophony, and oxymoron, which are further strengthened by internal rhythm and external rhyme. This paradoxical nature of his prose style is sure to intrigue his readers.

The influence of Saadi’s works extends far and wide, with notable figures such as Goethe and Pushkin drawing inspiration from his writings. Western exposure to Saadi’s works began with Andre du Ryer’s partial French translation of “Gulistan” in 1634, followed by Adam Olearius’s complete translation of “Bustan” and “Gulistan” into German in 1654. Hegel, in his “Lectures on Aesthetics,” recognized the rich development of pantheistic poetry in the Islamic world, particularly among the Persians, singling out Saadi as a master of didactic poetry.

Saadi’s impact also reached beyond literature, with the French physicist Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot’s third given name being derived from Saadi’s own. Voltaire, who admired Saadi’s works, particularly “Gulistan,” was known to enjoy being called “Saadi” as a nickname among his friends. Even U.S. President Barack Obama quoted Saadi in his New Year’s greeting to the people of Iran, demonstrating the enduring relevance of Saadi’s words and their ability to connect people across time and space.

Saadi’s legacy is honored annually on 21 April, when a crowd of foreign tourists and Iranians gather at his tomb to commemorate the day. This special occasion marks the completion of “Gulistan” in 1256, serving as a testament to the timeless impact of Saadi’s literary contributions.