Arshad Mahmood Awan

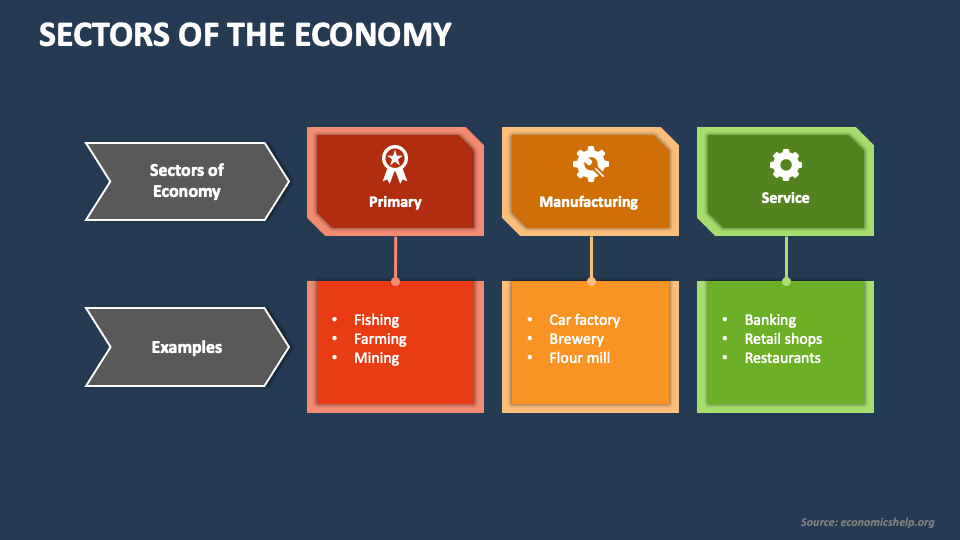

Agriculture in Pakistan, alongside other powerful sectors like bureaucracy, wholesalers, retailers, and textile exporters, has historically been one of the country’s economic “sacred cows.” For decades, successive governments have shied away from taxing the agricultural sector or implementing meaningful reforms. The reasoning behind this hesitance is rooted in political fear: taxes or reforms could provoke the wrath of powerful agricultural stakeholders who benefit from the current system. Agriculture, which accounts for about a quarter of Pakistan’s GDP and employs nearly 40% of the labor force, has long been too large and influential for politicians to challenge. However, as Pakistan faces mounting economic pressures, change may finally be on the horizon.

For years, agriculture has been largely exempt from the taxation system. Despite its size and economic importance, the sector contributes only a meager 0.1% to the nation’s total tax revenue. This disparity highlights not only the need for proper taxation but also the political sensitivities involved. Even good policies, if poorly executed, have the potential to destabilize the system and upset the many powerful groups that benefit from the current setup. As a result, previous governments have avoided addressing agriculture’s contribution to the national tax base, leaving the sector’s vast potential untapped.

Yet, in a significant policy shift, the legislative landscape is starting to change. Recent developments show that the provinces of Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have approved Agriculture Income Tax (AIT) legislation, with progress underway in Sindh and Balochistan. This new push to tax agriculture comes amidst increased pressure from international financial institutions, particularly the IMF, to improve revenue collection. According to a report by the German political foundation Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Pakistan could generate up to Rs65 billion through AIT — a much-needed infusion of revenue that could help stabilize the country’s finances.

This new move to tax agriculture is a promising sign for Pakistan’s economy, but it’s not without its challenges. One of the primary concerns is how effective tax collection will be and who will bear the burden of the new taxes. Historically, Pakistan’s taxation efforts have struggled to meet targets. In the first half of the current fiscal year (July-December), the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) fell short of its Rs6.01 trillion target by Rs386 billion, despite promises of stricter enforcement and penalties for tax evaders, including restrictions on travel abroad for non-filers. The hope is that the AIT will be different — that it will be implemented more effectively and that the tax burden will be fairly distributed.

However, there are reasons to be cautious. As with previous tax initiatives, the salaried classes are likely to feel the brunt of the burden. If the AIT results in higher food prices, it could disproportionately affect middle-income and lower-income consumers. This would render the new tax scheme largely ineffective, as the very people who are meant to benefit from improved agricultural efficiency would suffer from the rising costs. It is crucial that the government ensures that those who stand to gain the most from the agricultural sector — primarily the wealthier, large landowners — actually pay their fair share of taxes.

The success of this initiative depends on ensuring that high earners within the agricultural sector, who have traditionally enjoyed substantial privileges, are held accountable. Furthermore, it’s essential that the funds generated by the AIT are directed towards addressing the deep-rooted inefficiencies in the sector. Pakistan’s agricultural industry is riddled with problems — a small number of wealthy landowners monopolize profits while poor farmers continue to be exploited. Addressing these inequalities is crucial for the reform to have meaningful and lasting effects.

Pl watch the video and subscribe to the YouTube channel of republicpolicy.com for quality podcasts:

The agricultural sector is also one of the most inefficient in the world. For instance, it uses 95% of the country’s freshwater resources, yet an alarming 60% of this water is wasted due to outdated irrigation practices. This waste, combined with inefficient farming methods and poor infrastructure, exacerbates the country’s food insecurity and reduces its competitiveness in global markets. Therefore, the tax revenue generated by AIT must not only be used to ensure equitable distribution among farmers but also to fund necessary infrastructure upgrades and the integration of modern technologies in agriculture.

Improving agricultural efficiency and sustainability should be top priorities for the government. The AIT should be seen as a tool to address the sector’s inefficiencies and promote better practices, such as the adoption of water-saving technologies, the use of high-quality seeds, and mechanization of farming. Without these improvements, the country will continue to struggle with low yields and food insecurity, further hindering the potential of the agricultural sector to contribute to economic growth.

Additionally, it is essential that the provincial governments effectively manage and oversee the allocation of AIT funds. For the tax to have a real impact, it must be spent wisely on projects that improve the livelihoods of small farmers and boost agricultural productivity. This includes investments in research and development, the promotion of sustainable farming techniques, and the establishment of modern infrastructure like irrigation systems and storage facilities.

In conclusion, the move to tax agriculture in Pakistan is a step in the right direction, but it is just the beginning. It is imperative that the government ensures the new taxes are collected effectively and fairly. While the potential for generating significant revenue is promising, the real challenge lies in how that revenue is spent. Pakistan’s agricultural sector is in dire need of reform and modernization, and the AIT could provide the necessary funding to address these issues. However, if the tax burden is passed onto the wrong people or if the collected funds are mismanaged, the reform will fail to achieve its goals. The real work begins after the taxes are passed, and it is essential that the government acts with transparency, fairness, and a clear commitment to improving the sector’s efficiency and equity.